Sustaining School Innovation Year After Year

By Ron Williamson and Barbara Blackburn

By Ron Williamson and Barbara Blackburn

Schools are under increasing pressure to dramatically improve the educational experience of students. Almost every principal is working with their staff and community to examine current practice, implement changes, and sustain them from year to year.

The experience of a principal in Tucson illustrates a common challenge. When she became principal she found that lots of improvement projects were underway, but almost all were the responsibility of an individual department or program. There was no unifying theme and no uniform purpose.

She described it as “lots of good people trying to do things that made a difference,” but there was little coordination among the projects. Across the campus, there was a lot of distrust, cynicism, and no interest in talking about the issues.

At her first staff meeting, the principal invited staff to write down their concerns, fears, and frustrations on index cards. The cards were collected and the principal placed them in a large paper bag. She then shared her vision for making this school high performing and invited the staff to join her on a journey to transform their school.

Those who attended became members of a newly constituted School Improvement Committee. The committee developed specific plans to improve literacy and mathematics instruction at the school and to create a safe learning environment for all students. The principal worked with those who did not attend to encourage their participation but also supported and assisted their efforts to transfer if so desired.

Three years later, this school was one of the highest performing in the district. Student achievement vastly improved. Far fewer students dropped out each year, and the school had one of the highest percentages of students taking advanced placement classes among district high schools.

Another leader, middle school principal Mary Clark, began her school year in a similar manner. She gave her teachers an “Invitation to a Fresh Start.”

Teachers wrote down anything that was holding them back from a fresh start to the new year, and then they held a celebratory event throwing all of the slips in a trash can. As she said to them, “Remember to treat yourself well, then release yourself from the past!”

Dynamics of the Change Process

These six characteristics of successful schools were originally developed by the North Central Regional Education Lab and updated by the Wisconsin Department of Public Education:

- A clear, strong and collectively held educational vision and institutional mission

- A strong, committed professional community with distributed leadership

- A focus on learning environments that promote high standards for student achievement

- Sustained professional development to improve learning

- Successful partnerships with parents and community organizations and agencies building a broad base of support

- A systematic plan for gathering evidence of success

All well and good, but the dilemma about making substantive changes to a school is that change is not quick. It rarely occurs in a single year, and you may not see the results for several years. That’s why it’s important to have a plan for sustaining growth and a long-term commitment to success.

Key to all sustained improvement efforts is the presence of a clear, mutually agreed to and collectively supported vision statement. It serves as the litmus test for all improvement efforts. Before any new idea is pursued, we should first ask: Does this activity align with our vision and support our agreed upon mission?

Second, never initiate a major change unless you are fully committed to providing long-term, high quality professional learning for those expected to implement the changes. There is a lot of evidence that the most important PD comes after an initiative has begun. Only then do teachers and others fully understand the implications of the project and have appropriate questions about implementation and support.

Finally, very few school improvement projects achieve everything they set out to achieve. Not only is it important to involve teachers and other school constituents in planning, but also it is important to involve them in monitoring implementation and helping to make any adjustments that might be needed, including pacing and PD needs.

What Works and Doesn’t Work with Innovation

One of the most powerful tools for sustaining change is the culture of your school. Schools characterized by a positive working relationship among teachers are more likely to succeed. A laissez-faire attitude by the principal will virtually assure poor implementation and ultimate failure. Principal participation bestows a stamp of legitimacy on any project and helps to sustain it after implementation.

Michael Fullan (2007) says that sustainable change boils down to three critical focal points. First is improving relationships among staff. Second is working together to create knowledge and sharing that knowledge with one another, and third, “coherence-making” or helping people make sense and give importance to their work.

Stages for Launching a Middle School Initiative

It’s a cliché but one that is accurate. Change takes time. You must build a strong foundation for change and allow time for the community of stakeholders to work through a thoughtful process.

At one middle school Ron worked with in suburban Chicago there was interest in redesigning the program to provide more time for some subjects and to ensure students left for high school with the knowledge and skills they needed to be successful.

► A person knowledgeable in middle school programs was asked to visit the district; review the current program; talk with students, teachers, and parents; and then make recommendations to the district.

► As a result of this review, the district decided to launch a school improvement project that involved teachers and parents in reviewing the program and making recommendations to strengthen offerings.

► Each group read about the topic, reviewed research, and talked about the school’s students. Each group developed recommendations that, when implemented, would change the school’s program.

► To monitor implementation, a steering committee of teachers and parents was organized. This committee was asked to review all recommendations and ensure they were aligned with the school’s mission.

► The steering committee created an implementation timeline and determined which recommendations would be the first to be implemented. They were also responsible for monitoring the implementation to ensure its long-term success.

Sustaining Success

Innovations are sustained when it becomes everyone’s job to make sure they continue. That means that resources, time and leadership must be provided so that people become committed to the changes.

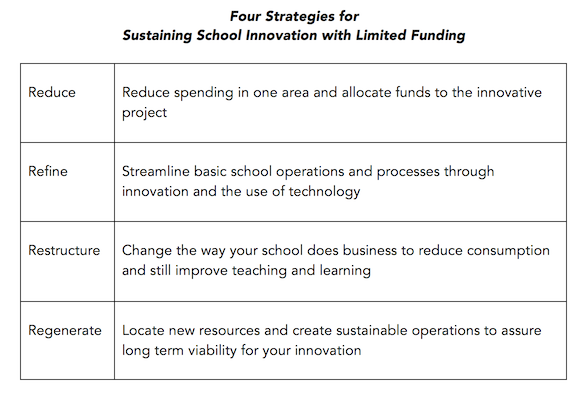

That said, it’s also true that we live in an age of diminishing resources. Here are strategies for sustaining school programs with limited funding.

A Final Thought

The most effective way to ensure success over the years is to develop a broad foundation of support. The enemy of sustained change is a “Lone Ranger” mentality. If you are the owner of the initiatives, they die as soon as your attention is directed elsewhere. Throughout the change process, build shared ownership within your school, seek outside community engagement and investment, and there will be long-lasting results.

References

Fullan, M. (2007). Leading in a culture of change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Johnston, J. H. & Williamson, R. (2014). Leading schools in an era of declining resources. New York: Routledge.

Wisconsin Department of Public Education (n.d.). Characteristics of successful schools.

________

Barbara Blackburn is a best-selling author of 15 books including Rigor is Not a Four Letter Word. A nationally recognized expert in the areas of rigor and motivation, she collaborates with schools and districts for professional development. Barbara can be reached through her website or her blog. She’s on Twitter @BarbBlackburn. Her latest book, Motivating Struggling Learners: 10 Ways to Build Student Success, was published in July 2015.

I really enjoyed the symbolic message of taking the cards and burning them. It allows teachers to feel school administration is going to work hard to extinguish some of the problems and work to create a better environment for students.

Something bothers me about this first principal: Did she do any valuing of the teachers’ opinions by considering what they wrote?

My takeaway from her action: “OK, you wrote your concerns down, which I’ll burn up. Now here’s what we’re going to do.”

It could have been done in a MUCH more acknowledging and powerful way if she wants stronger buy in.