The Do’s and Don’ts of Good Homework Policy

A MiddleWeb Blog

When I was a teenager in the 1980s, there was a commercial with a young man looking directly at the camera lamenting, “Homework! Homework! Gimme a break!”

When I was a teenager in the 1980s, there was a commercial with a young man looking directly at the camera lamenting, “Homework! Homework! Gimme a break!”

At the time, I could not exactly relate to him because I was one of the kids who knew how to “do” school well and actually enjoyed it. I also did little homework at home because I was also one of those kids who broke the rules and generally did homework assignments during class while the teacher was instructing.

All that changed after the publication of “A Nation At Risk” – when our schools began to be seen as failing and the homework levels increased. Then I empathized with the boy in that candy bar commercial.

Homework has been the most hated part of school for decades, and that’s not going to change. However, public perception of the efficacy of homework is cyclical – with each cycle reshaping homework policies and practices in our classrooms. That’s something we can change.

Some of the history behind homework

In the 1940s, when the country was dealing with more important issues, homework was seen as a redundant waste of time. After Sputnik, it was the way we would beat the Russians to the moon. The resulting backlash (post-moon landing) led to my elementary school years in the blissful 1970s when more problem solving, hands-on learning was emphasized.

After the dire “A Nation At Risk” warnings, the emphasis was on drill and kill in the 80s and 90s. This prepared the way for the piling on of homework as supplemental test prep after the passage of No Child Left Behind in the early 2000s and its even greater emphasis on rote learning.

We are now seeing the detrimental effects of this overtaxing of our children in the form of anxiety, attention issues, and increased family stress. The result is a lot of necessary conversation around the topic of the value of homework.

The homework domino effect

We recently had the homework discussion at my school, after listening to feedback from parents. One of the conclusions we reached: many of my colleagues would love to give less homework, but they feel that they would be doing a disservice to the students by not sufficiently preparing them for the next level of their education (HS), which gives significantly more homework.

Sidebar: This, in my opinion, is a major problem in education today—we don’t allow children to be the age they are and push them too far too fast with developmentally inappropriate practices.

The high school feels the pressure to give excessive homework to enable students to pass the Advanced Placement tests and to do well on college entrance exams. Universities see students who are “unprepared” to do the critical thinking necessary to be successful because, sadly, they were given too much rote work at the high school level and below. The effects of all these conflicting goals roll downhill to educators at the middle and elementary school levels.

Homework teaches compliance, not responsibility

Although I am thrilled with the recent trend in elementary schools (which tend to be the most progressive level of education) – eliminating homework in response to research – I don’t see this moving up through the grade levels any time soon.

Therefore, I am continuing to follow my gut on this issue and do what I think is right for my students. I’ve always been an educator who believes in family time and have never given homework on weekends or over holidays, but I am also very mindful of work I give on weeknights.

I was in a recent Twitter chat with other middle school educators about the topic of homework. There was a clear division among the teachers on the question of whether homework teaches time management and responsibility.

Giving two or more hours of homework after they have already spent seven hours sitting and absorbing feels like making children clock in for a second shift. I worked two jobs during college and was miserable, exhausted, and didn’t enjoy my classes as much as I should have. I see the same in my students.

I also feel that if teaching time in school is used effectively, not much homework needs to be given. When I do give homework, I make every effort to make it engaging, meaningful, and brief.

Applying what I’ve learned about motivation

During my time as a special education teacher, I had no control over the assignments my students were given by other teachers. In those years, I witnessed a lot of ineffective teaching – and some that was sheer brilliance.

When I began teaching English in 2008, I wanted to be more like the excellent teachers I’d known. I never wanted my classes to feel like a “sit and get” experience that students must somehow survive.

I began my quest to make all of my classwork, and resulting homework, motivating and useful to my students. This included an intense study of motivation while obtaining my graduate degree in Education Psychology.

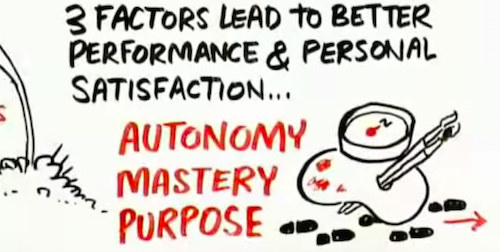

As luck would have it, much of what I learned in my graduate courses was summed up brilliantly in Daniel Pink’s groundbreaking book, Drive, which arrived on the scene during my first year teaching English (and was neatly summarized in an early example of the animated YouTube lecture).

In Drive, Pink presents a three-part test for homework:

- Am I offering my students autonomy over how and when to do this work?

- Does this assignment promote mastery by offering a novel, engaging task (as opposed to rote reformulation of something already covered in class)?

- Do my students understand the purpose of the assignment? That is, can they see how doing this additional activity at home contributes to the larger enterprise in which the class is engaged?

I have used these guiding principles for all work I give in class as well as for home. As Pink says, “With a little thought and effort, we can turn homework into homelearning.”

One of my other touchstone middle school teaching texts is the classic Day One and Beyond by Rick Wormeli. In it, he says, “Homework given to keep students busy regardless of whether it clarifies, reinforces, or prepares students is irresponsible.” I wholeheartedly agree.

The Do’s and Don’ts of Positive Homework

Through all of my research, and from trial and error in my own class, I have determined my own set of “rules.” Following practices like these can assure we have a positive homework policy in place.

Don’ts

- I do not use homework to introduce a new concept. If students are learning the concept on their own, then they are teaching themselves and what is my role? What’s more, muddling their way through unconnected information may frustrate more than enlighten.

I never give busywork (rote worksheets) as homework. When I do want students to practice problems with a right or wrong answer, we do so in class, and I formulate the problems as collaborative challenges. Plus, I believe that if homework can be copied, it will be. Why would I give a homework assignment that could easily be passed around and shared by all? Who learns from that?

- I make sure that the homework I assign is never too difficult for my students to do without assistance. Just because it’s homework does not mean that it is family work. I much prefer my students discuss what they learned in school with their parents rather than battle over something none of them may fully understand. Tears and arguments over homework are not the hallmarks of rigorous thought.

- I don’t grade homework for correctness. Often I will give a few points for completing homework, but homework never counts for more than 10% of the final grade in my class (thank you, Rick Wormeli). If it is intended to be practice of what they are learning, then it is unethical to mark students down for errors.

- I feel that “No Homework” passes send the wrong message that homework is unnecessary and can be skipped. I would much prefer accepting homework late than chastising a student who did not have their work finished on time.

- I don’t assign homework as students are ready to walk out the door during the last few minutes of class. When there is going to be some homework, I want them to begin it in class so that I can help answer any questions or clarify directions.

Do’s

- Students are more likely to complete assignments if they have an audience. Much of the work done in my class is shared and/or displayed.

- Our school uses a common calendar for each grade so that students don’t have more than two quizzes, tests, or projects due on any given day and also not after a large evening school event.

- For anything more complex than just finishing a small amount of what they started in class, I give more than one day for assignments to be completed so students may parse their time as needed.

I only give homework that requires original thought and a meaningful product, not simply the consumption of paper. Students are motivated by work that stresses creativity and higher-order thinking skills. No “language arts and craft” for me.

- My homework assignments are a deeper dive into the topic we study and always reach at least the application of the knowledge, not memorization. To the greatest extent possible, I allow students to choose how the work is completed and encourage creativity.

- I reduce homework by using my class time as effectively as possible. If there is vocabulary they need to know, for example, we work with it often and in many different ways in order to cement the information in their brains. I don’t use the rote memorization of vocabulary as homework because then it is in and out of their brains quickly.

- My homework is always developmentally appropriate. For middle school students, this means taking advantage of their desire to still have fun and see the absurd side of life, while simultaneously using their critical thinking skills. It is also work they are able to complete independently.

- I do not assign homework that necessitates the gathering of numerous, expensive materials or the use of resources (especially electronic) that they may not have. I am mindful that the only level playing field is my classroom.

In my ideal world, there would not be homework unless it was student chosen, developed, and executed. Until I live in that world, I do what I believe is right for my students. I don’t want to be the teacher that causes them to totally stress out and learn to dread school.

Please leave your thoughts about homework policies here in the Comments section!

I agree with the homework dos and don’ts. Less is more and should make sense and be purposeful with the whys discussed before the assignment. Different due dates for things like journals based on when the students want it due (depending on their at-home and afterschool schedules) is also useful. This does teach them to take responsibility for their decisions.

Our school has a no homework policy. It’s not really a policy per se, but if a parent complains that there is no homework provided, the principal will support the teacher in response to the parent and cite research that homework does not increase proficiency in a skill and the kids need/deserve down time or time to be outside. That being said, there is always research to contradict other research out there .

I do believe the homework should be available to students.

I like your idea about it being developmentally appropriate, fostering independence and creativity, etc. but what are the specifics? What structures, routines and procedures do you implement in you class that support a homework policy for reading and writing?

Thank you for an informative article that speaks right to the heart of this Special Education Middle School teacher. I agree with you that the only level playing field is right here in our presence where we can create community and autonomy if we do so intentionally.