Helping Students Thrive in “Cultures of Dignity”

Rosalind Wiseman’s Owning Up, a social emotional learning program for grades 6-9, is published in partnership with Corwin and AMLE.

Rosalind Wiseman’s Owning Up, a social emotional learning program for grades 6-9, is published in partnership with Corwin and AMLE.

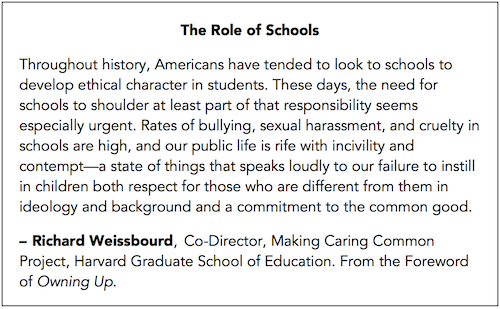

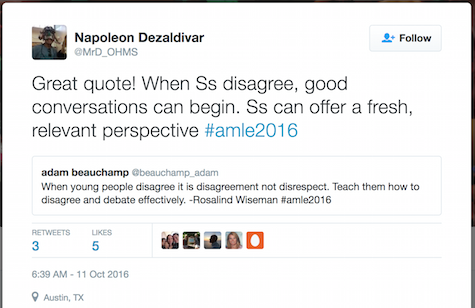

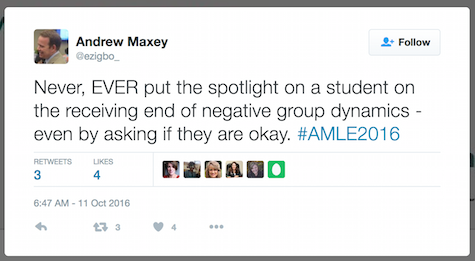

We rarely invite authors to promote books directly in MiddleWeb articles. But after reading the recent #AMLE2016 tweets during Rosalind Wiseman’s keynote, we decided to make an exception.

In this excerpt we’ve adapted from Owning Up, Wiseman describes a comprehensive tool to build cultures of dignity and common caring in schools that serve adolescents. (The snipped tweets suggest support for Wiseman’s ideas but are not meant to be endorsements.)

Owning Up is a tool to help you work with the most interesting, funny, and challenging people in the world: tweens and teens.

It’s also a tool to teach young people the capacity to understand their individual development in relation to group behavior with their peers, the social dynamics that lead to discrimination and bigotry, and the skills to be socially competent in the difficult yet common social conflicts they experience.

“]Whether you’re teaching Owning Up in a school, a team, or a youth-serving organization, what you will have in your hands is a flexible, dynamic curriculum that respects your knowledge of the young people you work with and the communities you operate in.

That said, Owning Up does have core principles, and we assume that educators who will implement Owning Up agree with the following:

✻ We are in partnership with the young people we work with, and they are often our best teachers.

✻ A young person’s academic success and engagement is interconnected with their social competency.

✻ “Soft skills”—the ability to work with others, negotiate conflict, and understand and respect the needs of others in balance with one’s own needs—is a difficult skill set to master and requires constant and graduated practice.

✻ To be credible and effective educators, adults must self-reflect on how they interact with young people. A culture of dignity is impossible if the adults don’t hold themselves to the same standards they demand of their students.

✻ No community is immune from abuses of power. But just as true is the possibility that any community can effectively address even the worst injustices that can occur within it.

Examining cultural constructs

Owning Up examines the cultural constructs that influence young people’s socialization. It incorporates cultural definitions of gender, sexism, racism, classism, homophobia, and other forms of “isms” that affect young people’s beliefs and decision making around self-esteem, friendships, group dynamics, and social and physical aggression.

But if you’ve taught this age group before, you know that implementing Owning Up, or any program like it, can be challenging because young people are rightfully skeptical.

They have endured unrealistic assemblies or character-building programs and heard too many superficial slogans that don’t reflect the complexity of the issues they face or include them as an essential part of the process to create solutions.

Worse, they’ve interacted with adults who demand their obedience and respect yet don’t treat them with the dignity that any person deserves, regardless of age.

In spite of the risk we are asking young people to take, we have seen time and time again that if adults listen to young people before we give them advice, they will take the leap of faith with us.

That is also what Owning Up is about: collaboration between educators and students to create honest discussion about the issues most challenging to young people – and to then help them find the courage, passion, and ability to create the world in which they want to live.

More about the specifics

Here’s a more specific breakdown of what Owning Up covers:

✻ Identify and discuss behaviors and attitudes associated with groups, popularity, trust, exclusion, and bullying.

✻ Understand the impact of how one expresses anger and learn strategies to effectively communicate when anxious or in conflict.

✻ Develop a plan of action when a friend or group demeans one or someone else.

✻ Recognize the influence of culture on individuals’ behavior and decision making, from friendships to academic engagement.

✻ Develop an understanding of how culture defines gender and race and how that can affect self-concept, self-expression, and interactions with others.

✻ Identify and strengthen support networks and personal standards in relationships.

✻ Clarify and promote the definition of consent—across the spectrum of young people’s interactions and relationships.

Owning Up‘s SEAL Strategy

A primary goal of Owning Up is to help students process their “messy” feelings (anger, sadness, frustration, anxiety) into a meaningful, substantive dialogue with another person.

In Owning Up, this is taught through the SEAL strategy. But like any strategy where young people are asked to put feelings into words and to use those words, the approach is often perceived by them as unrealistic and “adult speak.”

So you shouldn’t be surprised if you get a lot of resistance from your students when you teach SEAL. They may think you are trying to put words in their mouths, or make them talk like a “robot.”

When that happens, we have found it helpful to say:

“Everyone’s probably going to experience a conflict where they lose their words or think of the thing they really wanted to say five minutes after the conversation (or argument) ended. SEAL is just a strategy to figure out how to speak your truth in those situations.”

Another way to think about introducing SEAL is to compare it to the students’ favorite games. Whether it’s a role-playing game, a sports game, an adventure game, or even a first-person shooter game, there are always battles or competitions to be found.

To get ready for that moment, a player considers his or her strengths, resources, lay of the land, position, or types of items they could gather—and then considers the same of their opponents: What are their strengths? How will they use the landscape? What are their powers? How can they avoid the lethal blow?

The point of the game is to do your best and “level up” so you’re more prepared and able to handle different situations the next time you play.

It’s the same thing with SEAL. SEAL enables someone to think through their strategy so they have the maximum possibility of handling themselves with mastery in the moment of conflict and discomfort. The “pushback” is the opposing force’s response: the things the other person can do to retaliate, put you on the defensive, or create confusion and distraction.

The only difference between a battle in a game and using SEAL in real life (and it’s a big one) is that instead of the goal being to win (i.e., total destruction of the other team), it’s to manage yourself in a conflict where you are taken seriously and you uphold the dignity of all involved.

Steps in the SEAL strategy

Stop: Breathe, observe, and ask yourself what the situation is about. Decide when and where you can talk to the person so the person will be most likely to listen to you.

Explain: Take your negative feelings and put them into words—be specific about what you don’t like and what you want to happen instead. You realize you are making a request, so you know you may not get what you want. But at least you are being clear with yourself and others.

Affirm and acknowledge: State your right to be treated with dignity by the other person and your responsibility to do the same. If appropriate, acknowledge your part in contributing to the situation.

Lock:

- Lock in the friendship: Decide to resolve the situation and continue being friends.

- Take a break: Decide to take a break from the friendship but agree to talk later about reestablishing the friendship.

- Lock out the friendship: Decide that you can’t be friends right now.

Even though Owning Up is filled with concrete strategies about what to say and do in various situations, these strategies will work only if the students use SEAL to come up with their own words.

If they try to precisely follow the script or think that’s what we are asking them to do, it won’t work. And it’s the same for you as the educator. In order to make your teaching efforts authentic and credible to your students, you also have to make Owning Up your own.

How to Talk About Gender

We discuss gender a lot in Owning Up, and that can be complicated as well. Many young people are challenging core assumptions about gender and demanding expanded gender definitions and expressions.

At the same time, negative and confining gender stereotypes still permeate our culture and people’s interactions with and perceptions of each other. Owning Up is taught in diverse communities that have different comfort levels with how a person expresses their gender. Our bottom line is that every person’s dignity must be respected. Every student has a right to feel comfortable, safe, and acknowledged.

Specifically, if you teach the session on dating and relationships, we encourage you to state at the beginning that you will be pronoun neutral so that all students feel included without having to “out” themselves.

Something you can say is, “I will be doing my best to not be gender specific when we talk about dating or relationships so that all students feel comfortable. And please feel free to make other suggestions so we can do our best to make everyone feel included in the conversation.”

After sections on conducting role plays and the dynamics of being a bystander in social interactions, Wiseman continues…

Will you be well-suited for this work?

If you love working with young people, if you’re okay with throwing out your carefully prepared lesson plan because your students have gotten really engaged in a discussion, and if you don’t take it personally when they argue with you, you’ll be a great Owning Up educator.

Too often adults don’t want to allow young people to have these uncomfortable conversations, but we think creating an environment where young people can passionately disagree while treating each other with dignity is one of the most important skills they can develop—and one we all benefit from when these young people become adults who can engage in constructive dialogue.

As a general rule, you want to create a learning environment where students can feel uncomfortable but not unsafe. In order to do this, you must first ask yourself how these issues push your own buttons. For example, what experiences of power over others have you had—especially as a young person—that impact your professional and personal life now?

Other questions are equally important. If your race is different from that of your students, do you feel comfortable talking to them about racism and different people’s experience with race? If you are close to them in age, how does that affect your teaching? Do some of the students intimidate you? Why? How do you handle this dynamic?

To help you with your own self-evaluation, we have included an individual assessment at the end of the Introduction and some “Check Your Baggage” opportunities embedded in the sessions where we ask you questions to help you prepare for the session you are about to teach.

Observe your students both inside and outside the teaching environment. Watch how they walk into the room and take their seats; observe where students group themselves in public spaces (the lunchroom, the hallways, a wall where students hang out).

Look at where socially powerful students place themselves in relation to adult authority figures. Do socially powerful students stay as far away as possible from a supervising teacher while waiting for the bus after school? Or, in contrast, do they feel comfortable occupying the same space as adults? Observing behavior patterns can give you important insights into the social structures of your students and how they may bring them into your classroom.

Also remember that students participate in different ways. One student will be better at verbal discussions, while another will contribute more comfortably through writing. Each means of expression is equally valid. Just remember to look for opportunities where students will have various ways to share personal experiences.

Moral courage, perseverance, and commitment

Owning Up addresses extremely challenging issues in our society. While we all want our students to be safe and healthy, creating strategies that truly enable this to happen takes moral courage, perseverance, and commitment.

Individuals responsible for the implementation of Owning Up are the cornerstone for its success in their community. They are teaching students to treat themselves and others with dignity. They are teaching them to educate themselves about power and privilege, oppression, personal accountability, and bearing witness when others oppress and discriminate against those who have less power.

Most important, they are empowering students to work as agents of positive change and influence in their own lives and in the lives of others.

Wiseman is also the author of the best-selling Queen Bees and Wannabes: Helping Your Daughter Survive Cliques, Gossip, Boyfriends, and the New Realities of Girl World (basis for the movie Mean Girls) – and, not to give boys short shrift, Masterminds & Wingmen: Helping Our Boys Cope with Schoolyard Power, Locker-Room Tests, Girlfriends, and the New Rules of Boy World.