Tools to Teach Writers to Distinguish Evidence

By Sarah Tantillo

By Sarah Tantillo

The more time I spend in classrooms trying to help students write effectively, the more I recognize how detailed and nuanced this process is, especially when it comes to selecting and explaining evidence.

I’ve explored this issue in several earlier posts here at MiddleWeb, including Help Student Writers Find the Best Evidence and Tools to Help Writers Explain Good Evidence. This second post was co-written with Jamison Fort, a 6th and 7th grade social studies teacher, based on his terrific multi-day lesson plan, “Sandra the Orangutan vs. Buenos Aires Zoo.”

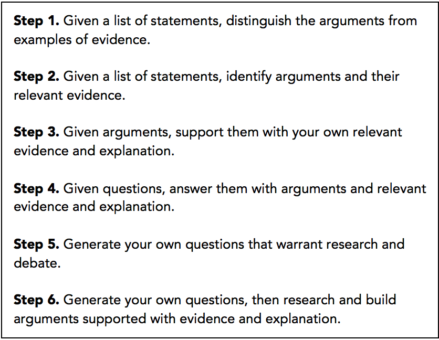

In our joint article, Jamison and I introduced a “Step 2.5” to my original six-step process shared in the first post:

In the second post, we concluded:

Students have a tendency to look simply for words or phrases that seem related, and often their quest for evidence is too superficial, which causes them to select evidence that is not helpful.

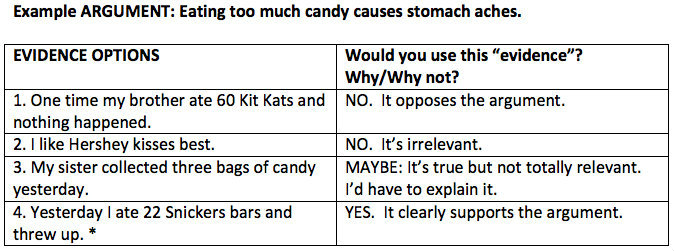

As part of a new Step 2.5, therefore, we’re teaching students what to rule out – the ineffective evidence. “Ineffective” evidence manifests one of three problems: 1) it opposes the argument, 2) it’s irrelevant, or 3) it’s true but not as relevant.

NOW: Here’s another angle to consider…

As I’ve noted in the previous posts, effective writers must do the following:

- Distinguish arguments from evidence (“Step 1,” explained here)

- Identify arguments and their relevant evidence (“Step 2,” explained here)

- Evaluate and select appropriate evidence (“Step 2.5,” explained above)

- Support arguments with relevant evidence and explanation (“Step 3,” explained here and here)

It turns out that the evaluation process for “Step 2.5” requires more than ruling out inappropriate/irrelevant evidence and selecting something better. Students must recognize that “imperfect” evidence can also be useful if explained properly. And they need to practice such explaining.

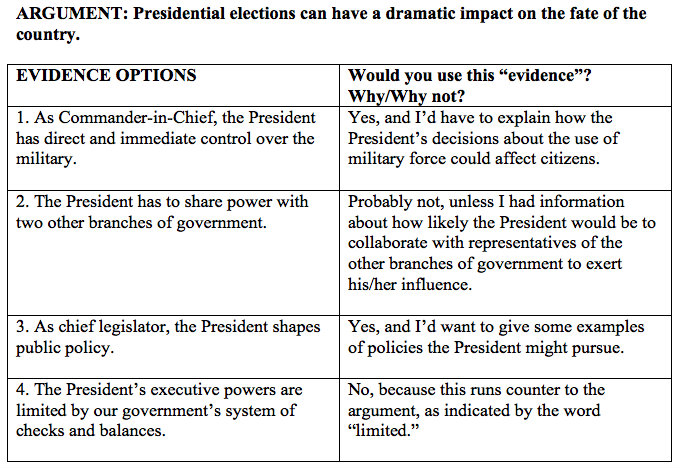

To illustrate this point, let’s revisit the example below from this earlier post. This exercise originally required students to evaluate potential evidence, select the best, then write a sentence that would follow logically from that choice.

Next logical sentence: Obviously, I had overdosed on sugar, and my stomach could not hold so much “content.”

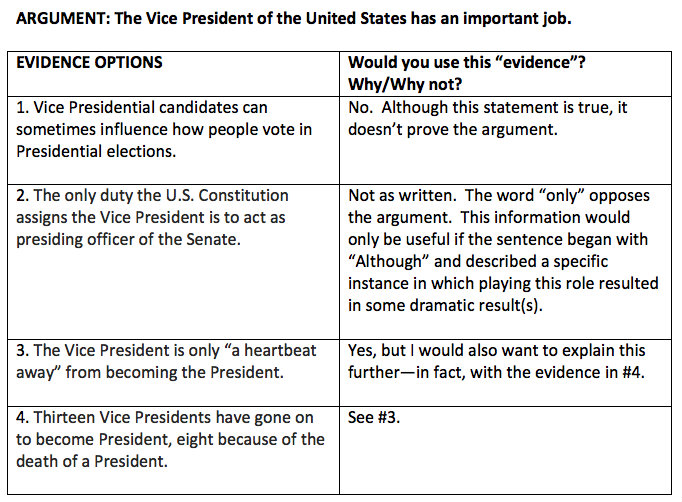

With that lesson in mind, we analyzed additional examples and asked students to explain how they could use the “maybe” evidence. Following are two answer keys to support this practice.

While going over these examples, we generated the next logical sentence for every “yes” or “maybe.” You can download the student version here.

It’s cross-curricular. Ideally, students should practice this approach in every class that requires them to write—so, every class. Effective selection and explanation of evidence is not “just an English class thing.”

What’s next? Take the training wheels off. Leave one row blank and ask students to fill it in with their own evidence and explanation. Then let them write their own paragraph using that evidence and explanation.

______________

Some additional ideas from my article in this very publication! https://goo.gl/f4VPeo