How I Became a Better Teacher in Macedonia

Interested in international teaching? In this article teacher Jordan Lucas, a world language educator who recently served in the Peace Corps in Macedonia, shares insights gained at the intersection of language and culture.

Being a Peace Corps volunteer is often touted as the “hardest job you’ll ever love.” Having been a middle school French teacher prior to joining the Peace Corps, I thought I had already found that job!

But my 27 months teaching English in a village school in Macedonia revealed a whole new dimension of professional practice. I became a more effective educator because of the culture and language learning I experienced alongside my students.

It was during this time that I truly learned the value of cultural contexts as a vehicle for language learning as well as using language(s) as a tool for discovering a culture from the “inside out.”

When at school, I worked with a local teacher to develop the English program in grades 1-6 as well as activities for the students, including clubs, camps and spelling bees. Throughout this process, I was continually challenged by my own cultural perception about school, learning, and life in general.

In the following account, I share some cultural perspectives and practices which enriched my language learning, shaped my own cultural identity, and contributed to my development as a foreign language teacher.

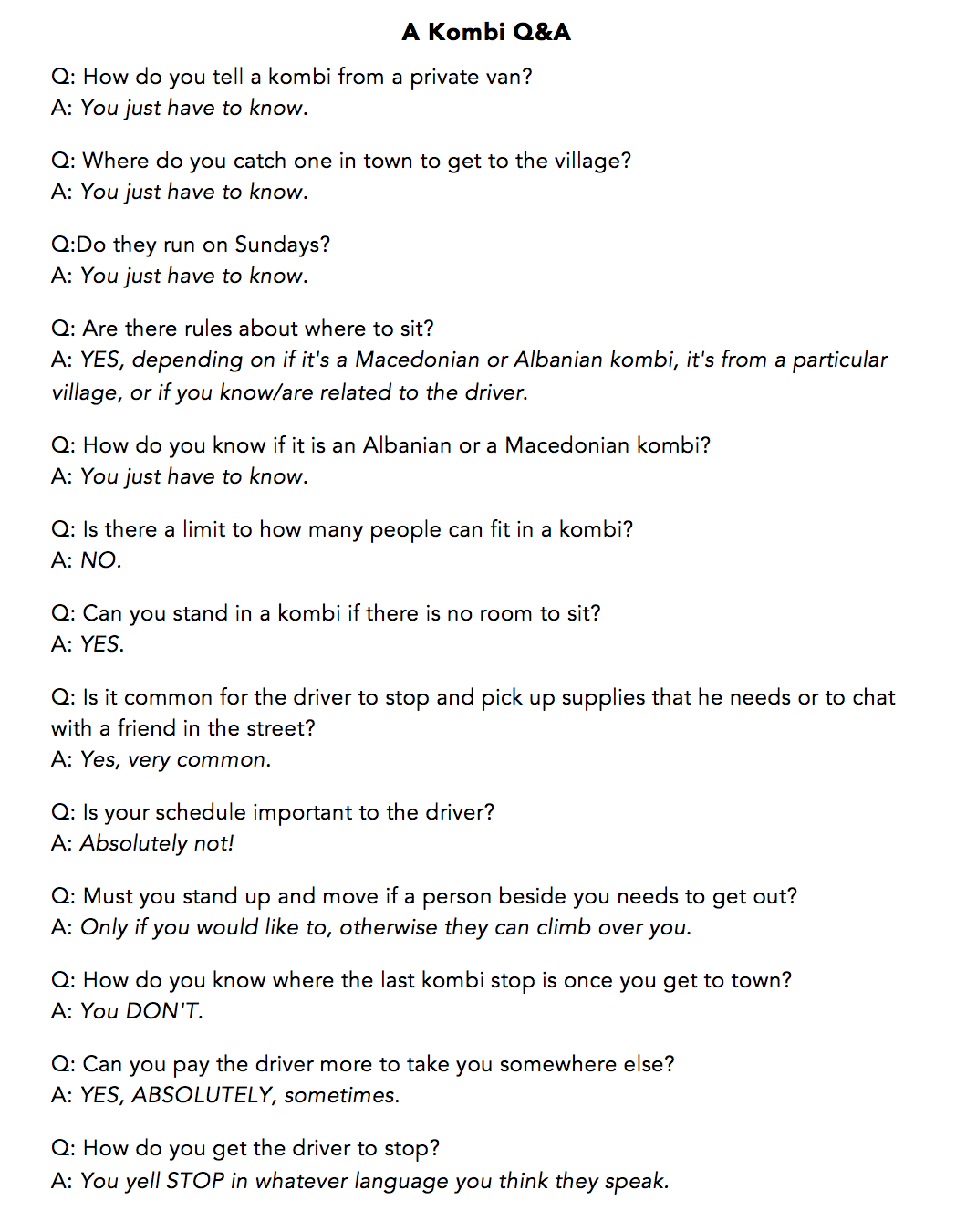

A Unique Cultural Teaching Tool: The Kombi

One cultural phenomenon of the Balkans and specifically of Macedonia is the kombi. Kombis are the main mode of transportation in Macedonia between any semi-metropolitan area and its surrounding villages, and often to the capital city of Skopje and to other countries.

A kombi is a van or mini-bus that contains about 6-8 seats. When I first arrived in Macedonia, I tried to mold the kombi experience into my own cultural context by waiting at a bus stop, trying to determine running times, particular fares, etc. After struggling to make the “kombi rules” fit into my own context, I finally realized that the bus stop really had no meaning and neither did “final destination” (or the schedule for the most part).

I could stand anywhere along the main road in the village and flag down a kombi to stop. I could get off at any point along the route. Though the length of time that this mode of transportation may take is very unpredictable, anywhere from 15 to 45 minutes to the city, I never saw a local resident complain. It is accepted that no passenger’s priorities are more important than those of any other passenger.

Over more than two years, I learned a lot about Albanian village culture just by observing and adapting on the kombi. While there are no official rules at all, the unspoken rules are very much rooted in the collective common sense of the culture.

The Cultural Perspective of Time:

има време/ Ka koha/ – “There is Time”

Time and how people observe time is very relative to culture. In Macedonia, time is a fluid concept and there is always enough time. Most importantly, there is always time for other people.

Prioritizing use of time is determined by one’s relationships with others; for example, who is getting married, having a baby, or visiting in the village. When you pay a visit to someone at their home, it is not uncommon to stay for 5 or 6 hours, especially if it is a special occasion. The hosts will generally put everything aside they are doing for their guests even if they have work to do or commitments the next day. “There is always time.”

If a friend or colleague extends an invitation for a coffee, this get-together could happen immediately or it could happen in a few months. There is generally no proposal like “Let’s do coffee on Tuesday at 4:00” because any number of things might happen on Tuesday that one cannot anticipate.

The Cultural Perspective of Personal Connections

Everyone in Macedonia is connected in some way. It is very rare to come across an “outsider” that no one knows or that no one has a connection to. It is not only a fundamental truth about the culture, but it is also an integral part of how society functions.

Albanian families are incredibly extensive, and in villages the more immediate family members usually live within close proximity. Not only does everyone seem to be a distant cousin or related through marriage, Albanians here will make an effort to find their connections to different families and individuals if you mention them in conversation, just to put those people into context for themselves.

Several times during my service here, people on kombis noticed that I was an “outsider” in the community. This occurred for any number of reasons, me speaking English, my accent when I speak Albanian, the way I was dressed, what I had with me (luggage). Sometimes people just started talking to me and realized that I wasn’t from there.

Learning to navigate the “pazaar” or “green market” in the local language and bargain with vendors on price was both a cultural and language learning experience.

On these occasions, the first question is generally “Who are you married to in the village?” or it might be “Are you American-American or really American-Albanian?” (There are several Albanians from the area living in America).

I understand now that when I was asked these questions, people were just trying to make a connection to me. Connections are the key to living, surviving and making sense of one’s surroundings in their culture.

The Cultural Perspective of

“Ti ke mesuar”/“You have learned”

Towards the end of my service, I heard this phrase on a weekly basis – “You have learned how to live here” – whenever I demonstrated some knowledge of an unspoken but practiced rule in the community.

People will generally tell you when you ask about rules: “it’s the Balkans.” One can interpret this phrase in one of two ways: there are no rules, or there are different, “Balkan” rules. The conclusion I came to is that there are rules, but they are ingrained in the collective “common sense” of the people in our village and surrounding region.

The kombi etiquette, for example, as evidenced in my explanations above, is a perfect example of this collective common sense. This collectivity of thinking is an aspect that binds the people and their culture together in this region.

Understanding this collective cultural mindset on a deep level makes someone an insider and therefore much more likely to be accepted and trusted as part of the collective whole. This combined belief and perspective was my greatest motivator for learning the language, and more than that, learning to speak the language like a local.

The Relationship Between

Language, Culture and Teaching

Culture is a key reason many language learners make the effort to learn a foreign language. Culture is therefore a necessary context for all language learning situations. Language and culture are so intertwined with respect to how and why language is used in certain situations that the two become inseparable.

The more I came to understand the Albanian culture in Macedonia, the more I understood how to be a representative of my own culture in the classroom. I was, on a daily basis, a walking, talking authentic representation of my culture for my students. I realized that if I had a difficult time learning about their culture while living among them, how much harder would it be for them to understand mine.

Although I’d taught English to foreign speakers in other settings, it had never been as important to me as it became in Macedonia, in that particular instructional setting, to contextualize the learning of English for my students through pictures, videos, scenarios, stories, music and any connections that I could make to their own lives.

When learning about transportation, for example, the word kombi was nowhere to be found in the books and the students needed to know why not. We engaged in conversations about why more people might drive in America and not ride in kombis and how “carpooling” might be similar.

We discussed the culture of size and space in American towns in comparison with the string of close-knit villages around us and decided that the kombis made sense because of the proximity of the villages and towns to one another.

Being familiar with their culture, I was better able to make comparisons for them between traditions and habits in America and in the English language and their own traditions and language usage.

What will I take from my

teaching experience in Macedonia?

One of my students wearing her traditional Albanian outfit at the opening of a new school in the neighboring village.

My time in Macedonia has greatly improved my ability to design instruction based on authentic cultural experiences and heightened my awareness of the need to relate language and culture in developing students’ language ability and interculturality.

In an authentic context, and as a language learner, I used language to investigate and explain for myself the relationships between cultural perception and unique practices in Macedonia. Through the lens of a language educator, I was able to better define how the idea of time, transportation, personal connections and language are interwoven to form a rich and complex culture.

In a teaching context, I hope to use this knowledge and expertise in the future to help others learn how to investigate, analyze, and explain culture through authentic language experiences.

NOTE: Jordan was supported in preparing this report by her former graduate school advisor Dr. Mary Lynn Redmond, Professor of Education and Coordinator of K-12 Foreign Language Education at Wake Forest University (NC).

____________

Jordan Lucas earned a BA in French and International Studies in 2009 from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an MAEd in French Education from Wake Forest University in 2010. She served in the Peace Corps in Macedonia from 2013-2015 as an English and Foreign Language (EFL) Teacher. In this capacity she taught grades 1-6 with a local Albanian teacher and worked on projects related to teaching, community development and cultural integration.

Prior to her Peace Corps service, Jordan was an English Teaching Assistant in France and taught French in Winston-Salem NC to students in grades 6-10. Most recently, upon completion of her Peace Corps service, she taught French in Chapel Hill.

Thank you for sharing your experience living in Macedonia. You make a strong argument for the important relationship between language and culture. Only by living and experiencing a different culture can this be truly understood.