Students Learn from Inquiry, Not Interrogation

Inquiry or interrogation? What if you asked your students which of these best describes their experience with classroom questioning? How do you think they would respond?

My colleague Beth Sattes and I have posed this question to a wide range of students. The majority choose “questioning as interrogation” as the best fit for their experience.

What makes them feel this way? Many believe that teachers ask questions to surface “right” answers, which students fear they don’t know. Others think teachers ask questions mostly to find out who is paying attention – or not!

Almost all students view follow-up questions as attempts to keep them on the “hot seat” and embarrass them for not knowing. And most perceive classroom questioning to be a competition that pits students against one another – Whose hand goes up first? Who answers most frequently?

Very few students understand questioning as a process for collaborative exploration of ideas and a means by which teachers and students alike are able to find out where they are in their learning and decide on next steps. This is one of the primary themes running through our work.

Students at the center

One of the primary purposes of quality questioning is to obtain formative feedback from students that teachers can use to decide where to go next during a lesson.

If students are not open to answering with what they think they know – even if they’re not sure – this purpose is thwarted from the get-go. And, if students are threatened or befuddled by follow-up questions (even those that teachers have planned in advance), they’re prone to either “freeze up” or become defensive.

Finally, if students don’t realize that the real value of questioning is to provide time for them to self-assess, to stop and think about their current understandings, then they usually find the pauses – the think times we create – to be embarrassing silences.

So, at the core of our approach to quality questioning is Partner With Students, a function we believe can transform students from “subjects” who feel under interrogation to active participants in a shared inquiry with their teacher and peers about where they are in their learning – and in wonderings about where they might take their understanding through deeper inquiry into the subject!

Click the image above to visit a class of 5th graders whose teacher

has invited them to partner with her in classroom questioning.

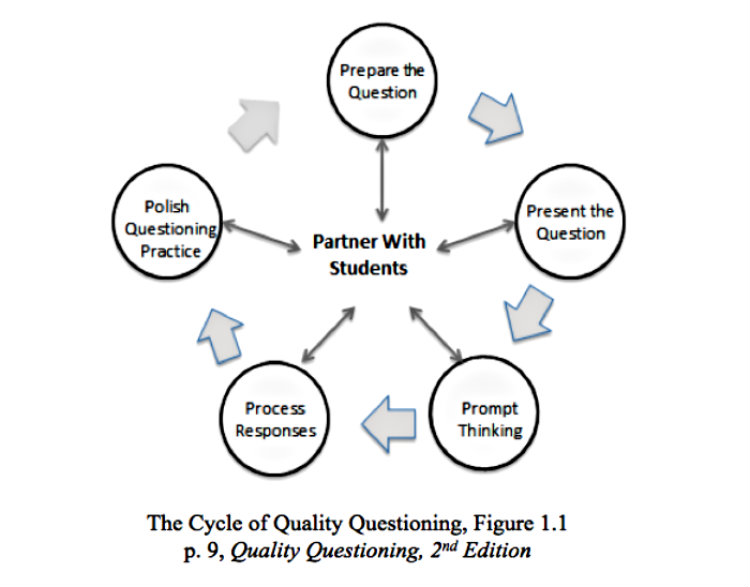

The graphic below displays the core components of the quality questioning process, indicating the relationship between and among the components. At each stage of the questioning cycle there are specific strategies teachers can use to nurture, encourage, and reinforce student ownership of the process. (Click to enlarge the image.)

Let’s explore three questions as we consider how best to partner with students in establishing new roles and responsibilities in classroom questioning.

1. What’s the point of questions?

First, it’s important to work with students to change their mindset about the purpose of questions – a mindset that has been reinforced for many since their first days in school. This mindset relates to the belief that teacher questions are intended to surface “right answers,” that incorrect responses aren’t of value – but to be avoided – and that student questions are usually inappropriate.

In our work, we’ve encountered teachers who engage their students in discussions about why they ask questions, about the value to learning of incorrect responses, and about the importance of student questions. These are the classrooms that are alive with inquiry – by both teachers and students. And, when students understand the relationship between questions and their learning, they are adding to their metacognitive knowledge.

Proactively hold forth the following expectations day in and day out. Students:

- Use teacher questions to prompt your thinking, not to guess the teacher’s answer.

- Ask questions when you are confused or need clarification – and to pose wonderings or inquire more deeply into the subject.

- Use follow-up questions to reflect on what you’ve said and why, and to make connections suggested in the teacher’s or a fellow student’s prompt.

2. Who will answer?

If questions are to provide information teachers can use to decide “where to next” in a lesson, then we cannot rely on just one response offered by an eager volunteer whose hand usually goes up first! This approach is fine if our goal is to determine if anyone was listening or if at least one student understood – but not if we’re committed to the learning of all.

This familiar practice leads to the “rich getting richer” – that is, to higher-achieving, more confident students having many more chances for learning and to low-achieving, under-motivated students being left out time and again. This has become such an embedded classroom routine that many students and teachers alike consider it normal.

But what is a teacher to do when students have become so conditioned to this practice over the years that many have completely opted out of questioning? Every student needs to believe that his or her answer is of value; that regardless of whether they understand yet, their teachers expect them to have their own answer when called upon. This, of course, ties back to their understanding the purpose of questions.

Two companion changes are required to change this mindset. First, as teachers, we have to eliminate hand-raising by volunteers as the method of choice for student answering – and substitute this with response structures that engage all class members in thinking and coming up with their best responses.

Think-pair-share is one tried and true alternative. When it makes sense to call on just one student during whole-class questioning, we recommend random selection. Popsicle sticks still work – as do random number generators! Second, we need once again to assist our students in understanding why we’re making this change in routine, and we can do this by establishing and reinforcing these expectations:

- Prepare to respond to all questions.

- Raise your hand to ask a question, not to answer.

- No opting out; you may “pass” if you don’t have anything to say yet, but you will be accountable to provide an answer later in the class.

3. What do we do with those ‘awkward silences’?

Think times are among the most powerful of questioning strategies. Think Time 1, a 3-5 second pause after a question is posed, is intended to afford all students with the opportunity to prepare to respond to every question.

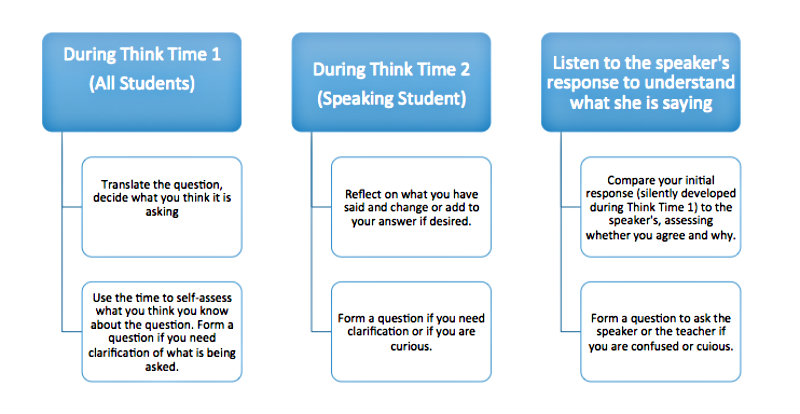

The purpose of Think Time 2, the 3-5 second pause following a student’s response to the question, is to allow both the speaking and the listening students time to reflect on and assess what has been said. This sounds good in theory, but it doesn’t work unless students understand the reasons for the pauses. They won’t if we don’t help them understand what to do with the time that many students refer to as “that awkward silence.” Consider how you might use the chart below to accomplish this end. (Click to enlarge)

Click below to return to the 5th grade teacher whose classroom we visited earlier.

Listen to her reflect on how she partnered with her students to create new understandings,

roles, and strategies related to the use of think times and related questioning practices.

Partnering + Planning: A Powerful Combination

Teachers who engage in advance planning of questions and questioning strategies are communicating how important they believe questioning to be to every student’s learning. (See my earlier article to learn more about the what and the why of advance planning for quality questioning.)

So what can happen when students believe that their teachers care – that they value each student’s learning and work hard to prepare questions that help students develop understanding? Students are much more open to the messages embedded in the partnership offers made by their teachers – more likely to assume new responsibilities for their own and others’ learning.

Planning and partnering are a powerful duo in converting traditional classroom questioning to quality questioning – in transforming student perceptions of questioning as a process of inquiry, not interrogation. Don’t wait. Invite your students to join you on this journey today!

Read Part 1 to learn more about

backward planning for quality questioning

______________

Why rectangular prism and not box? Could you have also shown an example of what you wish to calculate?

Great question! And one for which I do not have the answer, Kristian. The purpose of the video was to illustrate student engagement in dialogue to make meaning and mathematical connections. I am not math teacher, but I will pass your question along to Marti (the teacher) and ask if she will respond. Thanks for your questions.

Hello Kristian,

The reason we used the term rectangular prism is because that is the term used in our Alabama Course of Study. Students start using these terms as early as first grade (maybe even kindergarten). We try to use the correct math terms when appropriate.

The math problem that we were working on was displayed on the board, but probably not very visible on the video. Our purpose was to illustrate the student engagement, as Jackie Walsh stated. Thank you for your questions!

Very interesting article. I am sharing to my Facebook page. Thanks for this!