How to Help Young Writers Find the Force

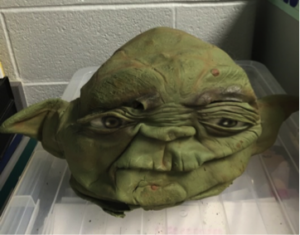

Each release of the latest Star Wars saga brings out my inner nerd. I love that LucasFilm and Disney Studios are continually reinventing the story for new, young audiences. It makes my classroom Yoda not seem so weird.

For educators, harnessing that “inner Yoda” is where it all begins.

Why Yoda?

One fall morning in a classroom far, far away, my colleague and friend Rasul brought me a gift. He walked into my classroom, smiling and pulled from behind his back a newspaper-stuffed rubber Yoda mask.

“Here,” he said, presenting me with this head of Yoda. “This is for you. I saw it, and it made me think of you.”

I wasn’t entirely sure this was a compliment.

“You don’t have to wear it.” He rolled his eyes and placed it on top of my then super-thick computer monitor. “Keep it here as a reminder that you are a Jedi Master. You see the force inside of all these kids, and you have this way of drawing it out; you help them see their potential.

You teach them to hone their skills. You believe in them, and that makes them believe that they can accomplish anything. You are the Jedi Master—of language arts.”

We are facilitators of learning, charged with making deep student connections, helping them seek understanding (of the content, of themselves, of each other, and of the world), and equipping them with the skills to find their own way, guiding them on their own paths to learning.

Encouraging Autonomy

When we include student voices in our planning, give them choices in process and product, and provide a context for doing so that transcends the grading book, students are motivated to learn and produce at levels higher than they ever imagined.

It’s not impossible to create such a learning environment, but it can be scary making the transition for the first time. Here are a few easy and practical ways to start gradually shifting control, embracing the force, and tapping into your inner Yoda in your ELA classroom.

1. Allow students to take part in the planning

There are many ways to do this; however, one of the easiest ways to include your students in your planning and get the most bang for your buck is by sending them on an Author Quest. Have them locate the official web sites of their favorite authors, searching for authorly advice on reading, writing, revising and editing. (Former middle school teacher Rick Riordan is a good example.)

Then, plan to incorporate this advice into your existing lessons or create new ones based on the advice. Author websites are an incredible untapped resource, full of author-tested words of wisdom for introducing lessons and enriching reading and writing curricula. In my classroom we’ve based our entire writing workshop model on the discovered advice of my students’ favorite authors and mine!

Lois Lowry’s words are both practical and inspirational in our workshop mini lessons: “Think about what you read: how the author made it interesting, or funny, or suspenseful. And write as much as you can, too. Keep a journal. Get together with friends who enjoy writing, and read things aloud to each other and talk about them.”

“Whether you intend to write a few paragraphs or a longer piece, think about the structure of your work before you begin. What do you want to say? What information do you need to convey? If it is a report, decide how to arrange the information. For short stories, have a clear idea of how you will start, what will happen, and how it will end. This will allow you to focus on the actual writing, so you are not trying to invent the story at the same time.”

It’s really cool to see whom your kids select as their virtual writing mentors, and it’s even more impressive to hear how they think the advice that they find can help inform reading and writing instruction.

Knowing that they are following in the footsteps and standing on the shoulders of actual published authors adds validity to any lesson or assignment, and the experience of contributing to the learning environment promotes student ownership of learning.

2. Provide opportunities for reflection and community building

The beginning of the second semester is the perfect time to get your students to reflect on their reading and writing growth. While personal reflection has its own merit, I suggest taking it one step further. Based on student reflections and upcoming curricular expectations, figure out with your students what classroom needs exist. Create a chart listing the lessons or concepts that your curriculum prescribes for each unit, and then allow your students’ needs to drive your instruction.

If, for example, in-text citation is a mini-lesson that you’d typically present in your argument unit, but most students already have the idea of how to properly cite references from a project they completed in science class, then there is no point in including that in your whole-class instruction.

Instead, ask your students if anyone feels that he or she has mastered this skill. Record the names of students who are willing to serve as classroom resources on the chart, so that all students know which of their peers they can turn to for assistance as they work.

Just as real authors look to their peers for support, it helps students recognize and utilize the writing talents of their classmates who have already mastered the skill.

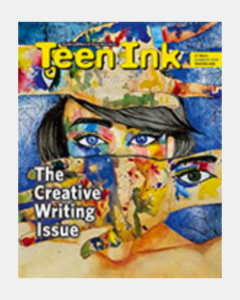

3. Provide purpose beyond a grade: Publish

I have come across many kids in my career who are simply not motivated by grades because they have never felt successful in my content area. These students need something more.

The expectation of publication beyond the classroom validates student effort, and the authentic purpose gives each of them a reason to want to write. It raises the bar for all students and levels the playing field for all learners.

Your students will never remember the grades that that they earned on their middle years assessments, but the power of publication is tangible evidence of their success that lasts forever.

4. If you are really brave, embrace the Pareto Principle

It’s also known as the 80/20 Rule. This one will require you to fully embrace your inner Yoda. And. Just. Let. Go. Similar to the premise behind Genius Hour, students spend 20% of their class time (one day a week) working on self-selected projects.

On this day in my classroom, students might engage in self-guided, real-world reading and writing tasks, such as studying mentor texts, experimenting with craft moves of favorite authors, collecting personal vocabulary and participating in all aspects of writing processes. They self-select genres, topics, and process with an end goal of real-world publication. The work that students produce during this 20% “free time” supports, fuels and inspires the remaining 80% of the week where we are engaged in the regular curriculum.

I started writing seriously when I was in eighth grade. I had an English teacher who encouraged me to submit my work for publication.” – Rick Riordan

The force is strong within our students

Their voices long to be heard across the galaxy, and they are seeking Jedi Masters – a.k.a., Master Teachers – who will encourage their creativity, nudge them out of their comfort zones and unleash their true potential to grow into innovative, self-reliant individuals who make an impact in their 21st century world.

Vicki Meigs-Kahlenberg is an experienced teacher, writer and consultant who is fascinated by behavioral economics and thrives on inspiring students to think critically by connecting their studies to the world around them.

In her two decades of middle school teaching, she has guided hundreds of students on their journeys to becoming published authors. Vicki is inspired by the students and teachers she meets, and she enjoys speaking at conferences and providing workshops for teachers, writing groups and classrooms. Follow her on Twitter @VMeigsK.

Feature image: Yoda

I love this Vicki! I have been mulling around some of these ideas in the past and have implemented some here and there. But, I keep getting interrupted by curriculum demands and expectations. I love the idea of listing lesson objectives and having students participate to make this list relevant to their needs as growing readers and writers.