Beyond Learning Styles & Multiple Intelligences

A MiddleWeb Blog

Learning What We REALLY Need to Know About our Students

Learning What We REALLY Need to Know About our Students

When we teach a class or watch our students, it often seems as if most (if not all) of them are having a similar learning experience. Underneath the surface, however, each individual is having his or her own unique ‘wrestle’ with the lesson.

In the past, I have often commented that it is what we do before and after class that determines the success (or failure) of a lesson. And I have long admired teachers who develop intricate systems of data collection that they use to diagnose student needs and to plan effective instructional supports.

These teachers are often the ones who are also working diligently to identify the aptitudes, academic strengths, and learning styles of each kid in their class. They have frequently caused me to reflect and wonder—am I learning what I really need to know about my students in order for them to be successful?

Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligences Have a Shaky Foundation

One widely embraced notion in modern education circles is that students are more successful when their teachers identify and tune their instruction to each student’s particular learning style(s). If you are my age, you likely have your own school memories of taking Gardner’s multiple intelligences test, Dunn’s learning style diagnostic, and of course, Gregorc’s ‘true colors’ mind-styles inventory.

For some reason, I always ended up being identified as ‘orange’ – in other words… random, abstract, adventurous…and according to my teachers…slightly erratic.

These types of tests have long since resonated with teachers. I think it’s because some part of us believes that our students will enjoy class more, engage longer, and reach higher learning goals if we work to match lessons and assessments to their individual learning preferences.

Though a multitude of books, theories, and online tools are available on the topic, there is no solid research indicating that students actually learn more when their teachers align instruction with their kiddos’ learning styles and/or intelligences (Hattie, 2012; Waterhouse, 2006; Willingham, Hughes, & Dobolyi, 2015).

In fact, some researchers even propose the opposite: that we should be teaching students the learning styles that they do NOT have (Apter, 2001). Furthermore, so far, no single cohesive definition of ‘learning style’ or ‘multiple intelligences’ has been put together.

The ‘prickly’ truth is that – despite countless hours of teacher effort and a mountain of good intentions – very little scientific acceptance exists of learning styles/multiple intelligence theory. Why? Because (despite lots of searching) there isn’t enough empirical evidence to support it.

What We Really Need to Know About Our Students

Don’t get me wrong. As educators, we need to know as much as we can about our students so we can help them attain academic success. But there are plenty of other, more useful things that we can learn about our class, such as what they already know, what they can already do, and what their strategies for thinking are.

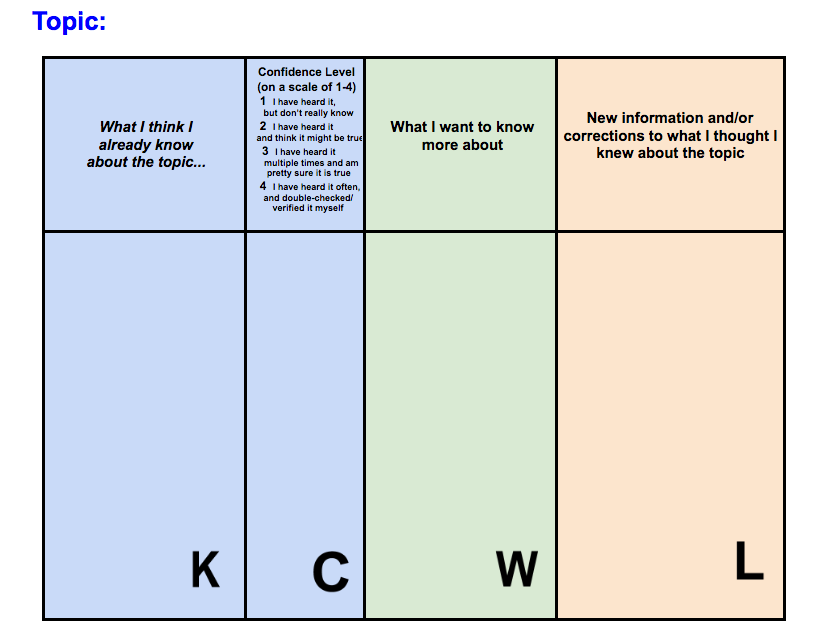

A key element of promoting deep learning is working with students to identify and activate prior knowledge. I like to use Google Docs to create (and share) beefed-up versions of KWL charts with my students. We call it a KCWL. Instead of just asking students to identify what they already know, what they would like to know, and what they have learned, this chart also asks them to identify their confidence level about the information that they have written down.

As we work with this tool, I also emphasize the need to make additions, adjustments, and revisions to the information or questions they started with. Since it’s a Google doc, students also have the option of working individually or collaboratively on it.

Tools to discover interest and focus

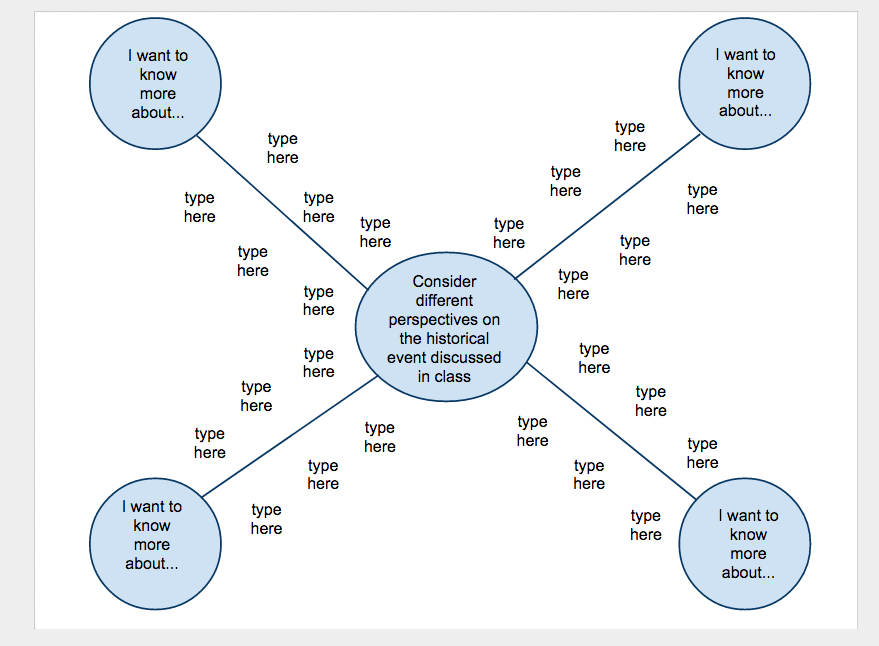

Students can also be asked to use mind-mapping and brainstorming tools to consider what they would most like to learn and what they might focus on in order to meet their learning goals (Pitler, Hubbell, & Kuhn, 2012).

In our first few attempts as a class, it often helps to have a template for them to fill in. Once students get comfortable, I ask them to select their own Google tools to do the same thing, or to explore a tool like Lucidchart, Mindmeister, Sketchboard or Coggle – all of which provide free online mind-mapping capabilities for teachers and their students.

One advantage to using digital tools rather than traditional chart paper is that the graphic organizers can be saved, edited, updated, shared, and stored.

It’s equally important for teachers to gain insight into the meta-cognitive capabilities of their students. Metacognition (sometimes described as “thinking about thinking”) refers to a higher-order of thinking where we exert active control over the cognitive processes involved in learning. In classroom terms: how do our students approach learning tasks and evaluate/monitor their progress.

It’s worthwhile to spend some time helping students identify and make sense of their own thought processes. One simple way to do this: have students team up in groups of two or three and take turns explaining how they would go about solving a given logic problem. The teacher can then use (or help students use) any of the mind-mapping or brainstorming tools listed above to map out various student problem solving approaches.

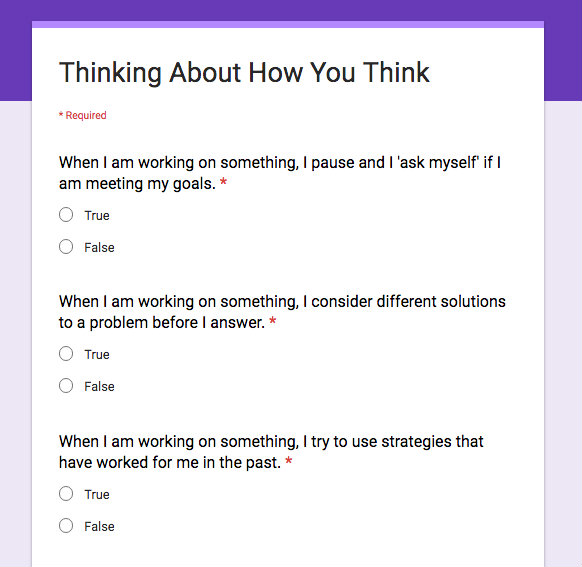

The Metacognitive Awareness Inventory

To discover more about an individual student’s thinking strategies, teachers can administer a short Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI). The MAI provides students with a way to self-report on what they know about cognition, as well as how they plan, monitor, evaluate, and trouble-shoot when trying to complete learning tasks. MAI also can provide insight about how students evaluate their success.

A widely utilized MAI for older students can be accessed here. I use Google Forms to administer my own online version to younger students and follow these guidelines to score and interpret the responses.

It helps my students and me to identify what thinking strategies they already utilize and also provides insight about which ones still need to be developed.

Spending Time on What Matters

Using an inventory or other tool to discover students’ learning preferences, multiple intelligences or mind styles is not going to help us meet the needs of students nearly as well as a systematic focus on readiness and thinking.

If we really want to improve teaching and learning, we need to work with students to identify what they already know, what they can already do, and what thinking strategies they use.

No teacher has ever had two students who were exactly alike. Each one is a unique blend of interest, experience, background knowledge, ability, and aptitude. As educators, we need to uncover as much as we can about each kid in our class. But we also need to make sure we spend our time (and theirs) learning about what is most likely to help them to be successful.

Download my references for this post

How do you help students think about their thinking and strengthen their learning strategies?

Very interesting and along the same lines as my work on what I term “Learning Intelligence”. I define this as our ability to manage our learning environment to meet our learning needs. My work with students shows if we can develop a set of skills, attitudes and behaviours whilst displaying certain attributes we can do this effectively. My experience shows many ‘unaccomplished’ learners lack “LQ” and, as a result, do not reach their true levels of ability, especially in schools where the learning environment can be quite toxic for them. After teaching for 30+ years I have given my time over to researching effective learning and set up a company to promote and distribute my ideas. More of LQ on my blog (50+ articles) but start with: http://wp.me/p2LphS-3p