Teaching Students to Set a Purpose for Reading

By Sarah Tantillo

By Sarah Tantillo

I think we can all agree that annotating texts helps students comprehend them more deeply. But not all forms of annotating are helpful. How you annotate matters a lot.

I’ve seen this problem quite often: students cover their texts with so many notes that it seems to take them an hour to read one page. The result? A dense, difficult-to-read mess.

While it’s great that students can annotate with generic strategies such as underlining topic sentences and starring supporting details, the truth is that they need to learn how to analyze texts more effectively and efficiently. It’s not efficient to notice everything. If you notice everything, that might be a sign that you can’t figure out what is most important.

How can we teach readers to determine what’s most important?

Students must learn to set a purpose for reading.

Too often, teachers set the purpose (with assignments such as “Read Chapter 7 and answer these three questions” or “Read this article and write a summary”), and students do not actually learn how to set a purpose on their own. Some might not even realize that they can.

And here’s an important follow-up question: “How could you tell?” Once students recognize the clues and characteristics of different genres, they can not only identify the genre but also explain its purpose (in this case, to persuade) and our purpose for reading it (to recognize the writer’s arguments and evaluate his/her support for those arguments).

When I was in high school, our chemistry teacher gave us an amazing assignment at the end of the year; he called it “Unknowns.” We received samples of different-colored chemicals/compounds and had to run experiments to figure out what each “unknown” consisted of. This assessment required us to demonstrate lab skills and content knowledge of the properties of elements we’d studied all year.

English teachers could take a similar approach with random texts: students would need to use clues to identify the genre and decide what purpose(s) they would set for reading.

Beyond using genre to set purpose, students can use other clues as well.

► When it comes to nonfiction/informational texts, it helps to look at the title of the text (no matter what size that text is—book, chapter, article, sub-section) and ask questions about that title. These questions—preferably “How” and “Why” questions—should guide our reading.

For example, an article titled “Lifting School Cell Phone Bans” would suggest questions such as, “Why should schools lift their cell phone bans?” and “Why do schools ban cell phones in the first place?” Presumably these questions would be answered in the text.

► When it comes to fiction/narratives, we can of course analyze text for a variety of purposes. For instance, we might ask students to focus on character development or the use of symbolism to convey meaning. But often when reading novels, we want students to read a chapter and figure out what’s important on their own.

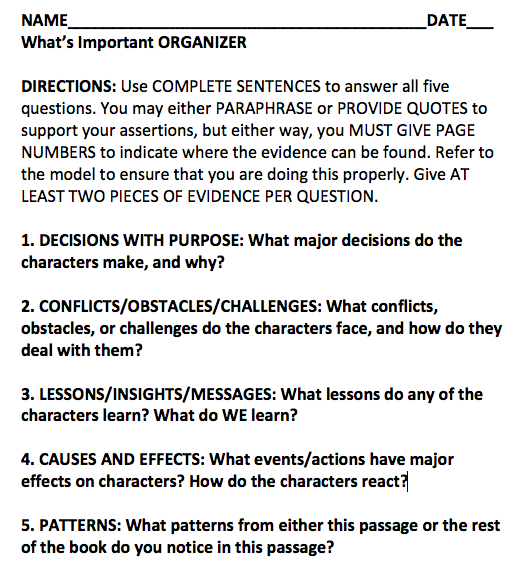

I’ve actually designed an organizer for this called (wait for it) the “What’s Important Organizer.”

I’ve previously blogged about the organizer HERE, and that original blog was adapted from The Literacy Cookbook.

Download the What’s Important ORGANIZER

Download a filled-in model of the organizer

In addition to training students in what to look for when reading any narrative, this organizer supports them in the practice of summarizing. Perhaps more importantly, it reminds them that there are specific things you should look for when reading a narrative in order to grasp its most fundamental ideas.

You don’t have to underline everything!

________________________

I found this information helpful and I will be implementing these these tips into my reading lessons in my English classes. Especially Fiction/Narratives: Focus on character development or the use of symbolism to convey meaning.

The why is important.