What All Students Need to Know about the News

At a recent workshop I conducted with secondary social studies educators, I surveyed them about their teaching of news and current events. What was clear was that most teach with the news, but few teach about it.

Students may see newscasts on TV, or read news on their social media feeds, but they may not really comprehend what goes on “behind-the-scenes” in the news gathering and reporting industries. This is where educators can help.

Just What is News?

This might sound like a simple question, but really it’s rather complicated. (Ask students this question and write their answers where all can see them. Are you surprised by their answers?) Wikipedia begins with this simple definition…

News is information about current events. Journalists provide news through many different media, based on word of mouth, printing, postal systems, broadcasting, electronic communication, and also on their own testimony, as witnesses of relevant events.

…but goes on to introduce other perspectives that begin to reveal the complexities of defining “the news,” including tone, objectivity, commercial value, reader impact, tabloid sensationalism, and much more.

Howard Schneider was the managing editor of New York’s Newsday newspaper. Like many newspapers, it includes sections like hard news, features, sports, editorials, entertainment. etc. Now he is Dean of the College of Journalism (which includes the Center for News Literacy) at Stony Brook University on Long Island, NY.

I heard Schneider speak at the first conference on news literacy where he emphasized the importance of making sure students understand what is news and where it resides. (Watch Schneider join other educators to talk about Why News Literacy Matters in this short video.

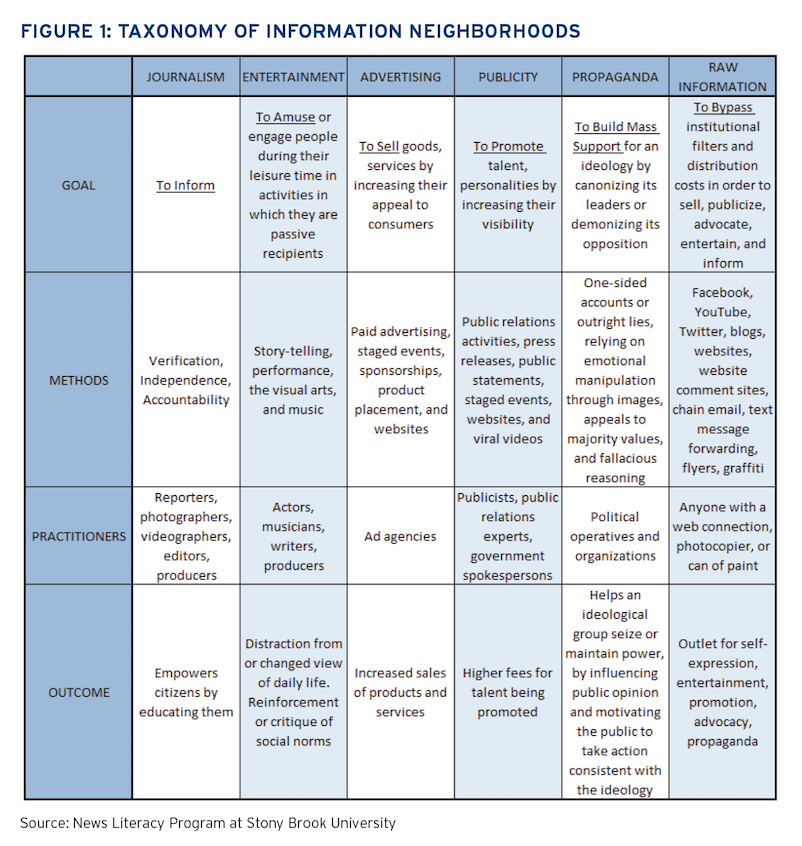

Schneider recommends that students first consider which one of six “information neighborhoods” they most often live in. For example, are they in the op-ed/editorial neighborhood; are they in the TMZ or Entertainment Tonight neighborhood; are they in the public relations or marketing neighborhoods? Or are they themselves producers of “raw information”? It’s an important distinction that this taxonomy helps define:

Using the chart (Figure 1)

► The top row of the chart lists institutions, organizations, or concepts.

► The first column lists four words that students might need clarification on.

- Goal describes what the organization hopes to accomplish;

- Methods describes the technique(s) used to achieve the goal;

- Practitioners describes the people (or careers) that work using those techniques to reach the goals; and

- Outcome describes what they hope to achieve.

Activity idea: Teachers might assign a row and a column (e.g., Advertising/Methods) to a student or group of students who must locate and identify a message that matches their assignment. Or the teacher might provide examples and have students decide where they fit on the chart.

Where Do Students Get Their News?

For many middle school students, curated news in social media might be the source of their news consumption, but parents and peers also play a part. Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat and Instagram are popular venues for news, but do students know that these social media companies are NOT news agencies? Similarly, Google and Yahoo don’t generate the news as much as they snag news from legitimate news sources and repost it. They are known as “news aggregators.” (Yahoo News, under the leadership of former network news anchor Katie Couric, does produces some “exclusive” reporting.)Activity idea: Ask students to brainstorm a list of all news sources. Document their responses on the board. You may decide to have a discussion with them about why a particular response may or may not be a real news source. After students have identified their sources of news, ask them who generates or produces that news? How do stories get into the newspaper or into a broadcast or in a social media feed? For the most part, they won’t know.

Here is a perfect opportunity for you to consider inviting a journalist or broadcaster into the classroom so that they can elaborate on the news gathering, reporting process. In the workshop I conducted recently, I moderated a panel discussion about “fake news” which included the executive editor of the local newspaper as well as the news director from a local TV station. Both representatives offered to not only come into the classroom and speak, but also conduct tours at their facilities for students. This is an appropriate way to begin to help students understand these news industries.

Who Decides the News?

So our students might watch a news anchor reading the news on TV, but what they might not know, or consider, is that someone else probably wrote the anchor’s words. That person is a news producer. (Have your students learn about other newsroom personnel here.)

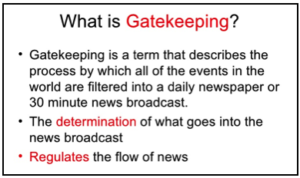

Ultimately, as the news producer I was the gatekeeper (deciding what constituted the news in our broadcast). Are students aware of that term? Newspapers and magazines also have individuals in “gatekeeper” roles, including executive editors, managing editors, and news editors.

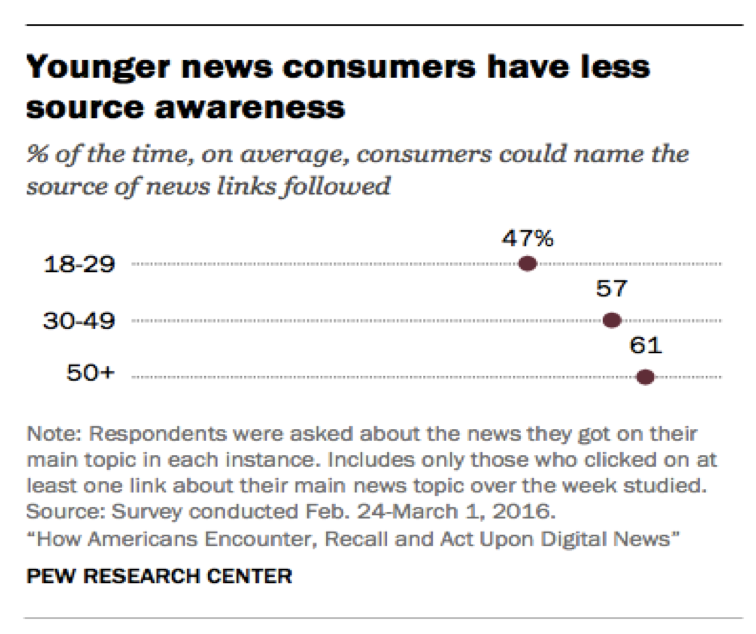

A recent survey revealed that many young people don’t always have “source awareness”—in other words they don’t know who (what person) or what (which organization) is responsible for having generated that news.

If students don’t consider this question, they may be guilty of forwarding a social media generated news story that could be illegitimate. (Ask your students if they’ve ever sent news to a friend without knowing the source? Or later realizing that it was fake?)

Another very important media literacy question is “what is omitted?” A 30 minute newscast is certainly not going to tell you everything you need to know, so where will students go to get news that was omitted?

The same applies to newspapers, which also have limited space. An interesting question for students might be, which news sources offer the most in-depth information? TV? Newspaper? Website? Are all TV newscasts equal? They might compare and contrast two different newscasts in their city and discuss what was similar and what was different, as well as what might have been omitted.)

Introduce your students to other key media literacy questions found in this NAMLE poster.

The News & Teaching Standards

Many educators already use the news to have students identify bias, propaganda and stereotypes in reporting. A good resource to consider is the “News In Education” initiative operated by many local newspapers. The American Press Institute’s “Introductory News Literacy” is a good example. It is a downloadable curriculum that is designed to introduce middle school students to “critical elements in news understanding and healthy processes for determining sources information and bias.”

News As a Business

Recently, many news organizations, on-air and in-print, have had to lay off reporters (and others) as advertising has moved online. Many newspapers and television stations have developed parallel online news publications and experimented with a model in which readers have to pay to read (putting the news behind a “paywall”) or experience intrusive advertising displays.

Ask your students if they would be willing to fund good journalism, and if so, how much would they be willing to pay? (Some communities are beginning to experiment with online non-profit news organizations or reading news created by hyper-local news networks like The Patch.) Might funding quality journalism be as simple as an online subscription to local news sources?

Editorial Pressures

Ask students to consider this scenario. Suppose they are either the TV news director or editor of a newspaper. Suppose the big story of the day is the recall of millions of cars due to a serious defect. (Is this newsworthy?)

Now suppose that that same car company is also your number one advertiser—either airing many ads during the newscast or purchasing full page ads in your paper. You know that you may risk offending the car company by reporting this news and that if you do, the car company might withdraw all of its ads, thus affecting your bottom line profits. Do you run the story or not?

This scenario is not too far from the real decisions that news organizations face on a regular basis. (Have your students review Balancing Business Pressure and Journalism Values, a document from the Poynter Institute written for news organizations.)

News Curriculum & Resources for Educators

By now, you might be curious about the various sources for helping students better understand the news. What follows is a brief list of recommendations.

News literacy curriculum for educators (American Press Institute)

News literacy resources (CoolToolsForSchools)

Lesson Plans (PBS Newshour)

Teachable Moments Blog (The News Literacy Project)

Digital Resource Center (Center for News Literacy)

News & Media Literacy Curriculum & Lessons (SchoolJournalism.org)

Frank’s new book Close Reading the Media: Literacy Lessons and Activities for Every Month of the School Year (December 2018) can help teach middle school students to become savvy consumers of the TV, print, and online media bombarding them every day. Pre-buy this timely book copublished by Routledge and MiddleWeb and use discount code MWEB1 for 20% off the cover price.

Thank you, Frank, for this essential essay and syllabus for teaching the news. Renee Hobbs gave a workshop in June about the need to stop using the term “fake news” and why – all part of media and news literacy. You’ve mapped it out for us.