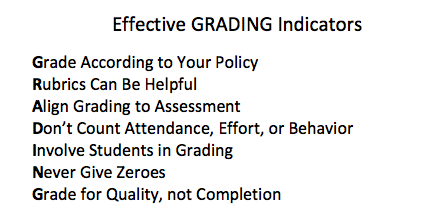

Teaching Tips: Don’t Forget 7 Grading Essentials

By Barbara Blackburn

By Barbara Blackburn

Grading is one of the most challenging parts of a rigorous classroom and no more so than for new and novice teachers. Many of the aspects of grading, such as whether to grade homework, are individual choices for a teacher. However, we should be careful to incorporate effective grading practices in all that we do.

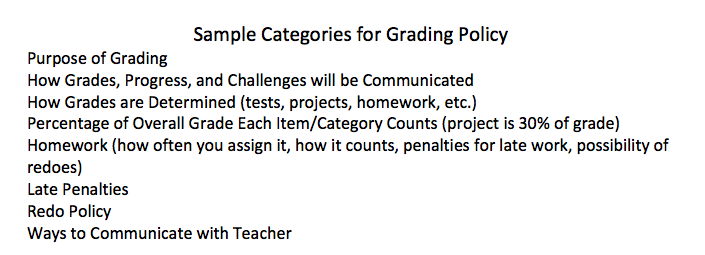

1. Grade According to a Policy

In a rigorous classroom, teachers provide a clear grading policy so that students and parents know what to expect. Ideally, you would work together with teachers at your grade level, in your team, or in your department so there is consistency. That may or may not be possible in your school.

Grading policies should be communicated early in the school year, ideally in writing. They are important for all grade levels, including the primary level. Remember to match the language and format of the policy to the level of your students.

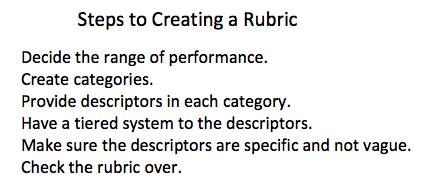

2. Rubrics Can Be Helpful

Rubrics are written descriptions of the criteria used to grade an assignment. They show students what they are expected to do. Todd Stanley in his book Performance-based Assessment for 21st Century Skills, provides six steps to creating rubrics.

3. Align Grading to Standards

It’s important to align your grading to your standards, goals, and objectives. That may sound basic, but I’ve often seen an assignment that called for certain outcomes based on the standards, but the grade was based on other criteria. How frustrating for a student.

I spoke with one teacher who assigned her students to write an extended response to a question. When she graded it, however, the items that were allocated the most points were neatness and spelling. Whether or not the student actually answered the question and provided evidence for the response were small portions of the grade. This isn’t fair to students. You can count those other items, but the main focus of your grade should be whether or not it meets the standards, goals, and objectives.

4. Don’t Count Effort, Behavior, or Attendance

One of the mistakes I made as a young teacher was grading for things that didn’t involve the actual work. For example, if a student “tried hard,” I gave them credit for their effort. So as long as they attempted to do the work, the student received partial credit, whether any of it was correct. I’ve since learned to give students multiple opportunities to complete the work correctly, along with coaching and encouragement, but effort alone does not qualify for a high grade.

Finally, it felt “normal” to incorporate attendance into grading. If a student was absent, I’d take points off for each day he or she was late with the assignment. It didn’t matter why they were absent; my policy demanded points taken off for late work. In effect, I penalized students because they weren’t at school. Some had good reasons for missing, some less so. But the bottom line was that I was choosing to grade, not their work, but on their presence or absence.

If I could jump in my teaching time machine and return to my classroom to do it again, I would remove these three factors from my grading. A grade should reflect the quality of work, not anything else.

5. Involve Students in Grading

Research affirms that students feel more ownership when they are involved in the grading process. So, involve them in the grading process. Be sure they understand what the grade represents, have them look at samples and grade the items themselves, ask them to self-assess their work, and let them create rubrics that make sense to them for your review.

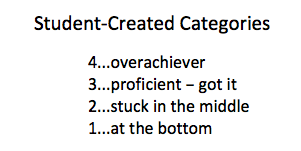

In one classroom, the students determined the levels for rubrics, using their own adolescent terminology.

As the teacher explained, “I didn’t particularly like the names for some of the levels, but the students chose them, so I stayed with them.”

After your students create the levels, guide them through the process of what would be an “A,” or “B,” etc. Talk about the quality indicators and how they relate mastery. Student ownership doesn’t mean you aren’t involved; it simply means you guide the process rather than doing it all yourself.

After the rubric is finished, ask students to assess a sample paper so they see how the rubric applies to actual work. Then, revise it together, and you can move forward with its use. It’s an excellent way for students to feel ownership and be invested in grading.

6. Never Give Zeroes

For some, that is a preferable alternative to doing the work. Perhaps they don’t fully understand the assignment, or they may not want to complete it. However, if we truly have high expectations for students, we don’t let them off the hook for learning. (Read these article to learn about other downsides of “zero” grades.)

7. Grade for Quality, not Completion

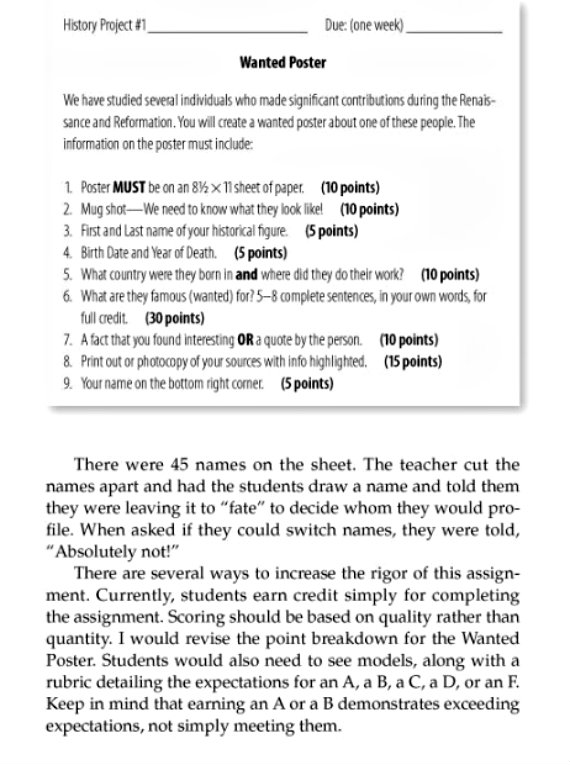

Also, be sure that your grade reflects the quality of the work and the evidence of understanding, not just completion or the quantity of included items. This is a particular danger when teachers determine grading for a project. With many tasks to accomplish, it’s tempting to assign points or values to every task or step just to keep students organized – and lose sight of the ultimate objective, a demonstration and assessment of learning.

I received a copy of an assignment for a tenth-grade honors course. Students had a week to complete the project. Take a look at this page from my book on rigor and assessment (p. 41):

A nationally recognized expert in the areas of rigor and motivation, she collaborates with schools and districts for professional development. Barbara can be reached through her website or her blog. Follow her on Twitter @BarbBlackburn.

There is a third alternative aside from “zeros or no zeros.”

https://lanewalker2013.wordpress.com/2017/08/01/why-zeros-on-student-work-are-important/

I appreciate Ms. Blackburn’s views and I do agree with most of her thoughts.

I must disagree on the issue of zeros. Not to be cruel or insensitive, but when a student misses one of my exams and then misses a well -announced time and date for the makeup, I feel that I must assign a zero. This is in fairness to the rest of the class who either took the exam at the scheduled time or took the makeup. Otherwise, I feel that this student took advantage of the test policy.