Strategies to Improve Writing in History Class

When I made the switch from teaching seventh to eighth grade last year, I hoped to promote more focus on learning specific reading and writing skills by tapping into students’ concerns about entering high school.

When I made the switch from teaching seventh to eighth grade last year, I hoped to promote more focus on learning specific reading and writing skills by tapping into students’ concerns about entering high school.

“Make sure you make them annotate their reading,” my then-freshman daughter told me. “All my teachers make us annotate like crazy.”

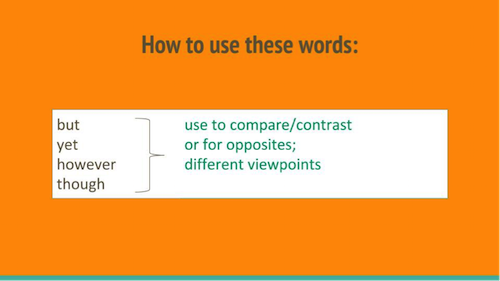

So one of the things I did with readings, early in the year, was to go through them line by line with my students and look for key sentences and words that would help them understand the text. The word “but” became a bit of a running joke in my classes because I kept pointing out what a significant role it played in nonfiction reading.

And then, an epiphany. Maybe this same approach could help them improve their writing. If words like “but” and “however” were useful signals to the reader, maybe they could also be useful words for the writer. I thought about this, but did little else – other than mention it offhandedly a few times.

Until this year. Until I learned about Judith Hochman’s writing revolution.

I actually bought the book

This summer, an article in American Educator by Judith C. Hochman and Natalie Wexler about how to teach writing grabbed my attention like nothing I’ve ever read before.

This post is not a book review, though. Full disclosure: I haven’t had time to read much beyond the first chapter of the book. That’s how good this book is – just the foreword, introduction and first chapter have already given me so many useful teaching strategies.

Take the first day of school. This year, our school decided to change things up and have team activities and assemblies on day one. I have strong opinions about the need for academic learning on first day so I wasn’t super thrilled about being in charge of a non-academic activity.

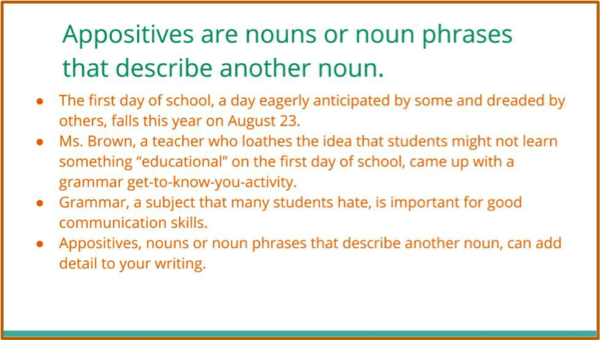

But then I recalled Hochman’s discussion about using appositives to raise the quality of writing. I created a get-to-know-you-activity that would teach students how to write sentences using appositives. Students would tell something about themselves and receive some grammar instruction that I hoped would pay off later in the school year.

Here’s how it went

I taught them what appositives were, briefly, using a slide that featured an appositive in every bullet:

I went on to show some more examples that introduced the other educators on our team – the math, science, ELA, special ed and foreign language teachers. Then a sentence about me:

Ms. Brown, a bit of a grammar freak, is the history teacher for 8-1.

Then it was their turn. Each student got a large index card and wrote sentences about themselves using an appositive. Later, we put these up on a bulletin board in our wing. I learned a little something about many of them:

Kayla, an eighth grader, visited her cousins this summer in Wisconsin.

A set from twins cleverly began: Josie, the cooler twin and Kate, the better twin.

Some were silly: Max, an alien from another planet, is posing as an eighth grader this year.

Some were pedestrian: Josh, the oldest in his family, will be entering high school next year.

Quite a few complained (though good-naturedly) about having to learn grammar on the first day of school. Jasmine wrote, “Jasmine, an eighth grader, thinks learning grammar on the first day of school is a terrible idea.” But more recently, a paragraph Jasmine wrote about the historical significance of John D. Rockefeller began with the following sentence:

John D. Rockefeller, an industrialist of the Gilded Age, revolutionized oil refining and created the first monopoly in the United States.

A dramatic improvement from the typical kinds of sentences I’ve seen in the past:

John D. Rockefeller was hugely important in U.S. history.

Victory! Pay-off!

Sorting out writing from speaking

Another helpful point from Hochman and Wexler is that teaching writing explicitly like this is worthwhile because writing is not like speaking. While you might use an appositive in conversation (My brother, the one who lives in L.A., is coming to town this week), students do not typically talk this way when speaking about historical content.

Students will say things like, “Well, Rockefeller was, like, a really important guy because he had the first monopoly.” So offering a template for writing more complex ideas than typically appear in student speech is a fundamental building block.

But, because, however, so . . .

So far, I have only used a handful of activities in class, but they have already had a significant return on my investment of time.

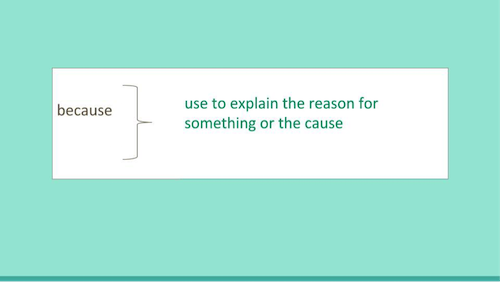

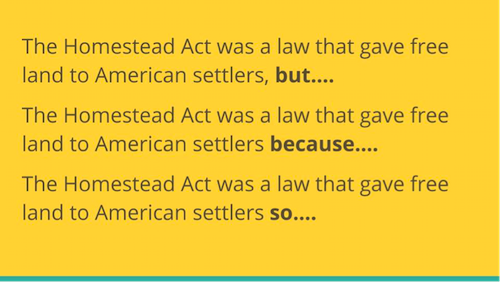

Hochman and Wexler suggest in their book teaching students to use words like “but,” “because” and “so” to make their writing more complex. I used the slides below to introduce the concept to students, explaining how the words can be used to write about history:

Then I asked students to write their own sentences about the content we were studying using the sentence stems below:

A few samples from students:

- The Homestead Act was a law that gave free land to American settlers but this led to problems with the Native Americans.

- The Homestead Act was a law that gave free land to American settlers because the government wanted to encourage westward expansion.

- The Homestead Act was a law that gave free land to American settlers so thousands of Americans began to move out west.

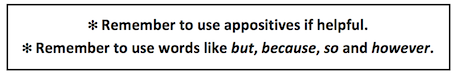

- As all things in teaching, this is a work in progress. Most of my students still struggle with writing, but I am seeing improvement. One thing I now do on most writing assignments, along with the instructions particular to the assignment, is to add the following reminders:

This serves to remind students to apply these skills they have learned earlier to their current writing. Their writing IS improving. (And on a personal note, it makes grading a far more positive experience!)

Other resources

For more help with writing, check out these Middleweb posts (just two among countless others):

- Sarah Tantillo, in a post about writing paragraphs offers helpful strategies easily adaptible for history class.

- Middleweb writers Shara Peters and Jody Passani take on the 5 paragraph essay.

Additionally, Glenn Wiebe’s History Tech blog offers a summarizing strategy that can help students elaborate on the “but, because, so” strategy.

I enjoyed this simple and clear post. I can’t wait to do this with 4th grade.

That’s the beauty of it—works for younger students. Start them early!

Hi everyone! I hope you are enjoying your summer! My name is Jo-Ann Slater. I am a 7th grade Middle School Social Studies teacher. I am currently working on a school improvement project and my main focus is incorporating more rigor into the classroom. I am looking for any resources that are available for helping students to improve with writing. They will be conducting a research project of their choosing this fall. I will also post all of the resources that I have obtained over the years. Thank you for your help in advance!

These posts by Sarah Cooper, also a Future of History blogger, can help students with research: https://www.middleweb.com/37411/helping-students-do-research-in-the-stacks/ and https://www.middleweb.com/23822/helping-students-grapple-with-primary-sources/. Sarah Tantillo discusses understanding evidence when writing in this MiddleWeb article: https://www.middleweb.com/33293/tools-to-teach-writers-to-distinguish-evidence/ . More on writing here: https://www.middleweb.com/33379/better-student-writing-10-middleweb-favorites/ . Barbara Blackburn, author of several books on rigor, wrote this article for MiddleWeb:

https://www.middleweb.com/27750/rigor-made-easy-3-ways-to-go-deeper/ A search for her at MiddleWeb – https://www.middleweb.com/?s=Barbara+Blackburn – will provide more related articles. Hope these help.

I love this! However, can I be a little nit-picky? As a grammar teacher, I feel pretty strongly about appositives being used to rename, relabel, or define. They act as nouns. They do not describe. Other than changing your definition, I’m definitely going to try this with my students!

I’m pretty sure I got that definition from Judith Hochman’s and Natalie Wexler’s book, but I appreciate the correction. I hope it works well with your students.