Support Students to Be Accountable for Learning

By Ron Williamson and Barbara R. Blackburn

Sharing accountability with students for their own learning doesn’t just happen. It must be planned for and supported. Yet, too often, when we design our accountability systems we don’t bring them fully into the mix.

Sharing accountability with students for their own learning doesn’t just happen. It must be planned for and supported. Yet, too often, when we design our accountability systems we don’t bring them fully into the mix.

One way to increase student ownership and responsibility is to require that they demonstrate understanding of content.

Here, we’ll share a leadership strategy that insists that students complete key assignments, assessments, and tasks at an appropriate level. Then we’ll address how leaders can support this piece of the accountability equation.

Expecting students to demonstrate learning

Too often students don’t complete work that requires a demonstration of learning. Typically this results in a low grade. We often think this means students learn the importance of responsibility, but more often what they learn is that if they are willing to take a lower grade or a zero, then they do not actually have to complete their work.

For some students in middle and high school, that’s a preferable alternative to doing the work we ask them to do. Perhaps they don’t fully understand the assignment; perhaps they don’t want to make the extra effort. Whatever the reason, if we truly have high expectations for students, we don’t let them off the hook for learning.

The use of a “Not Yet” or “Incomplete” policy for unfinished projects and assignments shifts the emphasis to learning and allows students to revise and resubmit work until it is at an acceptable level. Requiring quality work that meets our expectations lets students know that the priority is learning, not simple completion of an assignment.

The importance of work completion

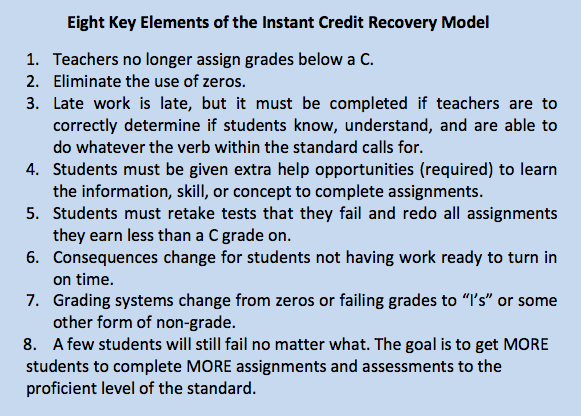

We had the opportunity to speak with Toni Eubank of the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB) state consortium. As part of their comprehensive school reform model, SREB has long been a proponent of holding students to high expectations for completed work. Eubank describes the model as “Instant Credit Recovery” (or Instant Content Recovery for middle school students). She told us:

This grading intervention practice requires that teachers rethink credit recovery completely. If it is okay for students to retake courses to meet standards, why is it not okay to retake tests that do not meet standards? Or revise essays, redo class-work and homework that do not meet standards?

Why do we let students “off the hook” for learning and for completing work that meets the standards during our classes, and then spend thousands and thousands of dollars requiring them to retake entire courses they have failed, or go into remedial programs – many times simply because they did not do homework?

Instead of sitting in classes throughout the semester or year, putting forth little to no effort, doing little work, failing tests or turning in garbage instead of high-quality work, students must now be required to work as they go. This method truly reflects job-embedded skills and habits and better prepares students for college and careers.

What Leaders Can Do

If school and teacher leaders want to bring about a similar approach in your school, your involvement is critical. Prior to implementation, it’s important to use shared decision-making to build ownership and garner the support of teachers for this initiative. As a part of this, you will need to introduce and reinforce the purpose of “not yet” grading, stressing its long-term impact on student learning and success.

It is almost impossible for teachers to incorporate “not yet” grading on their own. First, they need you to offer appropriate professional development so they understand the aspects of this type of grading, as well as seeing practical examples of related strategies. This may take the form of workshops, webinars, or book studies.

Next, it’s helpful to provide the opportunity for selected teachers to visit other schools that have implemented “not yet” grading. This will allow teachers to see the process in action as well as ask a variety of questions. If this is not practical, consider inviting teachers from another school to come to your school. For teachers, seeing is believing.

You’ll also need to encourage your teachers throughout the process. There will be bumps along the road, and it’s easy to become frustrated with the extra time that “not yet” grading takes initially.

One particular obstacle teachers will face is resistance from students, some of whom have developed the habit of “learned helplessness.” This is another reason to implement “not yet” grading on a school-wide basis, rather than having students complain “my other teachers don’t make me do this.” School leadership’s help in lessening and negating this challenge is critically important.

Resistance from Parents

Finally, there will be initial resistance (as well as some support) from parents and families. Although your teachers will take the primary role in ongoing communication, how you introduce the concept to parents and families is critical to the program’s success.

We recommend finding multiple ways to share information with parents and families. Options include PTO/PTA/Parent and Family meetings, school newsletters and email blasts, social media, and one page fact sheets.

A particular concern you will hear from parents (and teachers) is that allowing students to redo work does not teach responsibility or prepare them for “real life.” We disagree. In adult life, at your job, you don’t usually have the option to say to your supervisor, “I don’t want to do the annual report. I’ll just take a zero.” In all likelihood, you will be held accountable for completing the report.

Additionally, when new employees are hired by a company, they are typically provided support and training. Then, if they make a mistake, they are likely shown how to prevent the mistake in their next attempt, or possibly provided a mentor. They are rarely fired (think, “punished with a zero”) for their first mistake.

A Final Note

Requiring students to complete their work at an acceptable level is critical to improving student achievement, learning, and long-term success. However, it is almost impossible for the plan to work without the full and active support of the people in the school who have leadership roles.

_____________________

Barbara Blackburn was recently named one of the Top 30 Global Gurus in Education. She is a best-selling author of 16 books including Rigor in Your School: A Toolkit for Leaders, 2nd Edition written with Ron Williamson. A nationally recognized expert in the areas of rigor and motivation, she collaborates with schools and districts for professional development. Barbara can be reached through her website or her blog. Follow her on Twitter @BarbBlackburn.

This article was very motivating to change the current teacher mindset “they just don’t care.”