How to Stop Ourselves from Doing All the Talking

A MiddleWeb Blog

Even more alarming is that studies have found English language learners are talking only about 4% of the school day. This can be a disturbing thought if we agree that those who do the talking are doing the learning.

What’s stopping us

Yet, there must be a reason behind why students are talking less and teachers are talking more.

In my experience, I’ve found a number of reasons why this might be true.

► When I have given students opportunities to talk or have seen this in 4-8 classrooms, there have been times when students are off topic. This tends to be frustrating as a teacher, especially when we have much to cover. And the further the students are from me (the teacher) physically, the further they are from the topic. I can’t be in all places to make sure they discuss what I’ve given them.

► Another frustration teachers express is that when students are given a discussion topic and everyone discusses, it gets too loud in the room. We question whether the students can even hear one another. Is this even a productive use of time? The lack of control can be wearisome.

With all of these concerns, many of us give up on student talk in the classroom. We throw our hands up at the notion of giving students the opportunity to discuss with one another because we’ve tried it before and it seemed to fail us.

Don’t let these setbacks get you down. Peer conversations are too important and need to be happening in classrooms every day.

Think about the students in your classroom that are learning English and learning content simultaneously. Though this seems like a challenge, they can do it with our support. And giving them intentionally planned opportunities to have conversations with their peers is an excellent scaffold.

Learning content and language together

When we serve students in grades 4-8 that are English language learners (ELLs), we should not wait until they are proficient in English before we expose them to content in English. Research says that our students can and should learn content and language together. Content and language should be intertwined and not separated. This has to happen through meaningful interactions.

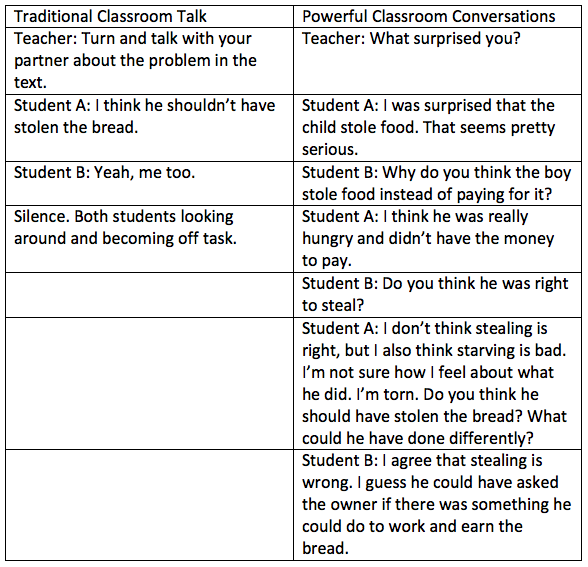

More often than not, when we hear kids talking in classrooms, they are participating in a “Turn and Talk.” Turn and Talk is not a bad practice. In fact, it is a good foundation for authentic conversations. However, it is not necessarily a meaningful interaction.

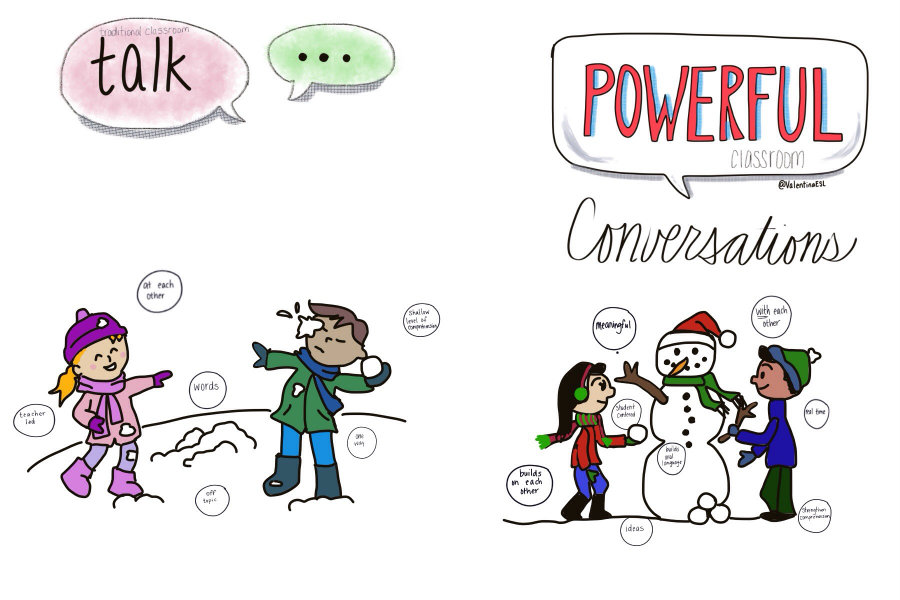

Our goal is that students can hold academic conversations that are meaningful interactions, but to get there we might need to provide students with scaffolded opportunities. We want our students to hold powerful conversations with one another – conversations where peers are discussing WITH one another and not AT each other.

When I picture these two scenarios in my mind, I picture the “Turn and Talk” like a snow ball fight where kids are throwing words AT each other. Some kids miss their target. Others dominate the game. Some don’t participate or hide behind a wall.

But the meaningful conversation is one where kids are building a snowman together out of ideas. Adding more, building on top of, rethinking and making something new that wasn’t there when they started.

The thing about conversation is that it’s more than simple talk. Conversation can’t happen alone. We have to teach our students how to work together and collaborate and think in real time. Thinking in real time means that they will have to immediately process the ideas they receive through oral input. They will need to deliver oral output and support it with their own ideas.

All of this is work. It’s hard work. In many ways holding an academic conversation is similar to writing an essay. Students express what they know and understand, but it is done orally and not in written form.

Scaffold with modeling expectations and with sentence starters

To support struggling students and ELLs through academic conversations, we can provide scaffolds. The first scaffold is to model our expectations. Students need to see what we expect of them so they can achieve it. Using a fishbowl or model group is effective. Select a group of students who exemplify correct conversation skills and ask them to do a mock conversation for the class to see. While they are sharing, point out the elements that you want to see from your students.

Another effective scaffold is sentence starters. Making sentence starters available in the classroom benefits every student, but struggling students and ELLs might need the extra linguistic support when they are discussing with their partner or group. During class, model the use of the sentence starters so students will understand how to access them.

Conversing in all content areas

Academic conversations should happen in all content areas. Students benefit from discussing their thoughts, perceptions, understandings, ideas in science, in math, in history, etc. The opportunity to converse with peers using domain specific vocabulary is invaluable. If students don’t practice this in our classrooms, when will they have the chance? It won’t happen when they are hanging out with friends. This is our chance to elevate their language and learning. We have to seize the moment.

Think about your own experiences. When you have a problem, question or deep thought, do you keep it to yourself? Perhaps you do. But many people take their concerns to a professional learning network, a community of peers, Twitter, Facebook, RTI, etc. and discuss it. Why? Because we know the power of conversation is great and learning is social. We learn from one another and from verbalizing our own thoughts.

When we don’t give students the time to process, negotiate for meaning, and collaborate, we have to wonder… are we supporting them as learners?