Can I Have a Do-Over? A Debate Gone Awry

A MiddleWeb Blog

But last month, when we did a debate in my eighth-grade history classes on whether the electoral college should be abolished, I finished the weeklong unit feeling I’d misstepped as a teacher in any number of ways.

It wasn’t one thing. Instead, the small fissures in the unit reminded me of poet William Stafford’s admonition in the context of a relationship, in “A Ritual to Read to Each Other,” that

…it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give – yes or no, or maybe –

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

Ultimately, I felt I wasn’t fully “awake” enough in planning this debate. And so afterward, I did a postmortem on what happened, so that it wouldn’t happen again and I wouldn’t feel like I’d missed the mark.

So what did happen?

- I stuck with an old topic instead of searching for a new one.

With my Constitution unit, I always try to end with a debate or consensus discussion. This kind of activity brings to life issues embedded in the document, often related to the Bill of Rights.

Many years in the past, I’ve done a very similar electoral college debate, with much more ultimate success. This year, I hesitated to do the topic because it felt a little stale to me for whatever reasons. But then I justified it to myself because the electoral college has been such a visible national issue since the 2016 election.

And I did change the unit slightly, adding an element that required every member of a group to find a fascinating article about the electoral college, add it to their group’s Google Doc, and have the option to use it in their final debate write-up. But this slight change yielded only slight additional interest.

A better approach – one that would have given me new energy – would have been to canvass students about their questions and concerns about the Constitution and base a debate or discussion on major issues that emerged. Or, even more problem-based and student-centered, to apply design thinking to the history classroom in a Constitution unit, as Jody Passanisi describes here.

- I didn’t think enough about how political the topic would feel.

In 2016, we had done this electoral college debate just before the presidential election, and it seemed informative and relevant. In late 2017, the topic felt world-weary to me.

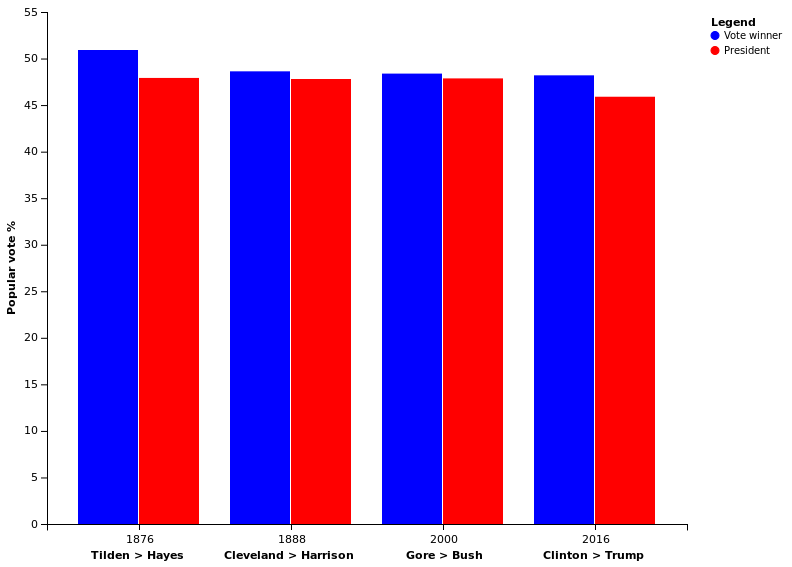

In addition, the mere topic of whether to abolish the electoral college felt unexpectedly liberal, given that Democrats lost the electoral vote but won the popular vote in both 2000 and 2016. And many of my most liberal students came in with sharp preconceived ideas about the topic from their parents’ discussion of both of those elections.

Below: US presidential elections when the popular vote winner received fewer electoral votes:

By Schmarrnintelligenz (Own work) via Wikimedia Commons

- I didn’t scaffold skills as much as I should have.

Last year by this time, we had done more projects that involved parenthetical MLA citation. This year, those projects will come later. As a result, I expected my students to know how to cite, but then I found myself in-filling the teaching of this skill on the fly, to mixed results.

Some students, even stronger ones, didn’t cite at all, and others did not paraphrase enough – a cocktail for some unfortunate accidental plagiarism that was largely my fault, not theirs. I marked off a little bit for it on the final drafts but didn’t feel I could truly blame students for it because I hadn’t taught the skills well enough. We are definitely revisiting this topic on the research paragraph students are working on right now.

- I didn’t give students enough of a chance to differentiate themselves from each other in the final assessment.

With most papers I assign these days, I look forward to reading what students write because the results vary very much. The written assessment for this debate, though – a 200-word paragraph giving each student’s point of view, from the perspective of his or her group’s state, on whether the electoral college should be abolished – yielded write-ups that, by definition, had to use many of the same arguments and language.

Interesting statistics and quotations livened up these papers a bit, but, whether you’re California or Alaska, the reasons your state musters are limited to only a few. And I found myself slipping in and out of concentration while I graded – not a recipe for teacher engagement.

Sure, they clawed their way into the debate as they always do, tenacious as ever, and I love seeing them spar and collaborate. But middle schoolers, at least mine, generally love arguing about any topic, so I think their enthusiasm was due more to the excitement of combat than to intrinsic interest in the topic.

So what’s the takeaway? The next time I’m unsure whether an assessment feels stale, I need to listen to myself – and either substitute a new project, if the curriculum allows, or infuse the old project with enough to make it seem new and unpredictable again – for me and for the students.

___________________________________________________________

Sarah, so good to see such self-analysis included in thinking about a lesson. It sounds like this lesson was still asking for a lot of higher-order thinking and debate.

Mary, thanks for your encouragement. Definitely, my goals were high!