Executive Function Is Key to Student Achievement

Executive function is the missing link to student achievement, Nancy Sulla believes. If students haven’t developed the brain-based skills to focus, catch and correct errors, identify cause-and-effect relationships, and more, they can’t make sense of lessons, no matter how well they’re designed.

When my sister and I were young and would misbehave, rarely of course, my father would sit us down to discuss our actions and the consequences of those actions. I remember we used to say, “Just punish us!”

We loathed the lengthy discussions of our wrong-doings. Our friends were either punished or grounded, but not us; we were engaged in discussion. I look back and think of how my father was a natural at teaching us cause-and-effect, seeing multiple sides to a situation, considering future consequences in light of current action, and more of what I now know to be the skills of executive function.

See if you can envision this. You have a 2” nail hammered partway into a piece of wood; your goal is to drive the nail all the way in. Have you got the picture? You start applying pressure with the palm of your hand; but no matter how hard or long you push, the nail does not move. You then step back from the situation and get a hammer. With a few quick strokes of the hammer, the nail moves through the wood to its destination.

You have students who attend class and have some background content but need to master a lot more to achieve at the desired level. You start teaching lessons and purchasing materials that break down the content into seemingly reasonable steps for one to learn. But your students aren’t achieving at the desired level.

You then take a step back and shift your focus to building executive function, and students begin achieving at higher levels of content mastery.

Do you see the metaphor here? Do you understand it? If so, you’ve just demonstrated your strength in executive function. Were you able to create a mental image of the nail-into-board scenario? Were you able to hold on to information while considering other information when you read the second paragraph after reading the first?

Were you able to consider the cause-and-effect relationships of hitting the nail with the palm of a hand versus hitting it with the hammer? Were you able to shift focus from one event to another when you ended the hammer-and-nail paragraph and read the executive function and achievement paragraph?

Were you able to think about multiple concepts simultaneously after reading both and engaging in a comparison? Were you able to focus and concentrate while reading those two paragraphs?

Having those italicized skills made the text accessible to you. If you did not have those skills, you could have read those paragraphs over and over again, to no avail. Trying harder wouldn’t have gotten you further down the road of understanding. These are just some of the skills of executive function: a set of skills that help direct the management of information and behavior.

The Internet requires executive function skills

Now consider a possible home scenario. You open a door, pushing it a little too hard; it slams into the wall behind it, punching a hole in the drywall.

You think, “I bet I can learn how to fix this and save the expense of hiring someone.” Where will you find out how to accomplish this task? With a quick Web search, you find a how-to sheet of directions with text and pictures. You also find a video of someone demonstrating and explaining the process. Easy!

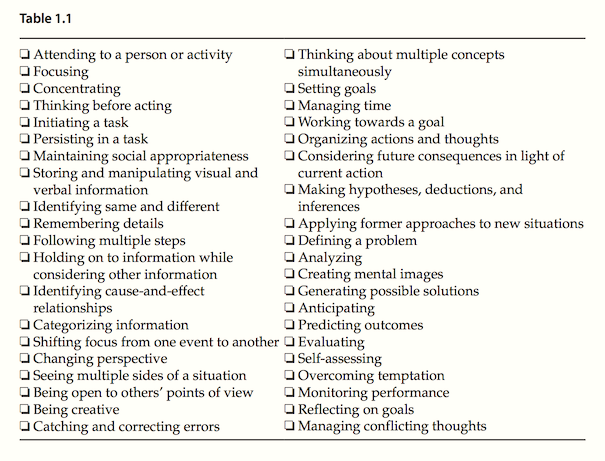

Well, not so fast. Review the list of executive function skills in Table 1.1 and check off the ones you will need in order to process this information you found – that is, to successfully follow the video or direction sheet and patch the hole.

If you search for “subtraction with regrouping,” you’ll find a wealth of resources. If you search for “light and shade in oil painting,” “basketball jump shot,” “how to use a gluestick,” or “balancing chemical equations,” you’ll likewise have no lack of resources.

Many of the skills and concepts students need to learn are readily available through a variety of sources on the Internet. This is far different from the accessibility to content that was available just a decade ago. What is important, however, is that you can identify a reliable source, and that requires executive function. Likewise, being able to take in the content information and translate that into learning requires executive function.

So, with all the “physical access” students may have to the Internet in school and at home, only the possession of strong executive function skills will provide them with the “cognitive access” to the content that will lead to learning. Physical access to content through lessons does not equal the cognitive access that leads to learning.

Without the skills of executive function, you cannot access the information needed to transform thinking and produce powerful learning. Executive function is, therefore, the coveted missing link to student achievement.”

Schools seeking to improve student achievement tend to invest in textbooks, computer programs, curricular programs, and related professional development on teaching lesson-level content. While an effective lesson and great materials may be necessary to learning, they are not sufficient to ensure learning. They will be to little or no avail with a student who lacks executive function.

The key to unlocking content and ensuring a pathway to long-term memory is through executive function.

What is executive function?

“The executive functions are a set of processes that all have to do with managing oneself and one’s resources in order to achieve a goal.” Executive function “is an umbrella term for the neurologically based skills involving mental control and self-regulation” (Cooper-Kahn, Dietzel, 2008, p. 10). While there is no one universally accepted definition of the term executive function, this one reflects most other definitions.

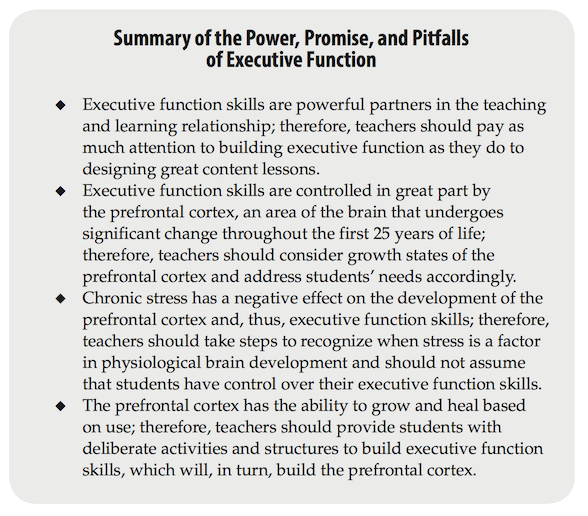

In my recent book Building Executive Function, I devote a portion of Chapter One to a straightforward explanation of the brain science behind this concept. In particular, I talk about the development of a young learner’s brain from the earliest years to adulthood, and how the more executive function skills students encounter, the more the prefrontal cortex grows.

I also examine the brain’s “pruning phase” during adolescence – a topic of particular interest to educators in grades 6-12. Understanding how these processes play out is essential to helping students – including students in very stressful life situations – maximize their development of executive function.

Covering all these key points in a brief article would be impossible, but I hope I’ve intrigued you enough to continue to investigate the relationship between building executive function and achieving student success.

Watch Nancy’s TED-Ed Dive talk about Students Taking Charge.