Teaching the Holocaust: Facts, Emotions, Morality

A MiddleWeb Blog

The idea for this post began as I was helping a student last spring write an essay for Language Arts on the strategy of Atticus Finch during the trial in Harper Lee’s classic book To Kill a Mockingbird.

The idea for this post began as I was helping a student last spring write an essay for Language Arts on the strategy of Atticus Finch during the trial in Harper Lee’s classic book To Kill a Mockingbird.

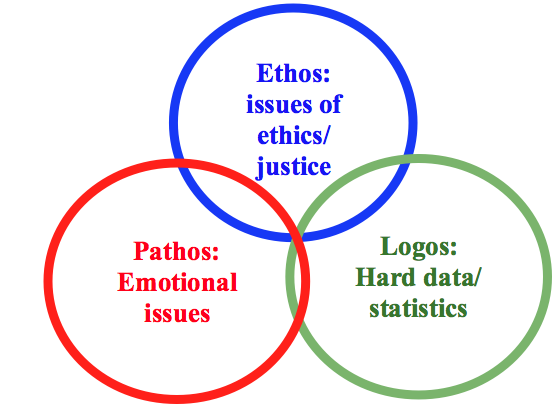

The assigned essay asked students to consider the extent to which Finch used the persuasive techniques of ethos, pathos and logos in his argument before the court.

Around the same time, I was preparing my unit on the Holocaust and looking to create several prompts for students to respond to it in an essay assignment.

I have always believed that a thoughtful approach to the study of the Holocaust must include consideration of both hard facts – the data, if you will – about what happened, and also some personal accounts to humanize the history.

As one of those writing prompts, I asked them to consider the advantages of using logos or logic to explain what happened compared with the advantages of pathos or emotion. Is one more important or valuable than the other in exploring Holocaust history? Or do you need both? (It was one of several prompts – see here for the others, if you like).

Beyond the staggering numbers

In particular, I expected students to focus on two films I had used to supplement the unit. The first, The Fallen of World War II, is an award-winning video with animated infographics that is absolutely mouth-dropping. There are a few minutes of it, roughly in the middle, that pertain specifically to the Holocaust. This is the “logos” part, that explains the numbers of people killed as a result of the Holocaust and where they were from. (There are two versions – the interactive version allows closer exploration.)

My favorite resource for the human story is the 2005 documentary, I’m Still Here: Real Diaries of Young People Who Lived During the Holocaust. This is an outstanding documentary – as long as you preview it in advance and perhaps cut a few scenes. (I omit one of the scenes near the end because I think it is too disturbing for my 8th graders. The cutting also helps get the 48-minute film within my 41 minute class periods.)

A student’s suggestion: understanding ethos

I was pleased with the logos/pathos prompt I created for the Holocaust essay. One of my students, however, went a step further and added the “ethos” part to the essay. Though ethos has more to do with relying on the character of a witness or the persuader, it can still be a useful tool for thinking about how to teach history if you interpret it more broadly to refer to ethical issues.

This is what my student did. He pointed out in his response that a class discussion we had on guilt vs. responsibility (using the now familiar classification of perpetrators, collaborators and bystanders) had led to his consideration of the ethical issues raised by the Holocaust.

Where ethos can take us

Take, for example, the internment of Japanese Americans in the U.S. during World War II. Surely, we need students to learn some basic facts about the issue: who was interned, when, and where. And students should also be exposed to the personal stories. An excellent resource for this is The Orange Story, a short film and accompanying website designed for students.

The film, though fictional, is historically accurate. Its brevity – 17 min – makes it well suited to show during class while allowing time for reflection and discussion. The accompanying website offers excellent additional resources and links, including some pertaining to “ethos.” American citizens of Japanese descent were stripped of their citizenship rights in a time of war. It’s not hard to see the ethics/justice discussions that emerge from that historical fact. (Thank you to the film’s producer, Jason Matsumoto, for introducing me to this resource.)

Most people, when asked about what they remember about history class, refer to the “logos” sorts of things: facts and dates. Surely, history must include facts. They are the nuts and bolts, essential tools to learning. But if this is all that our class is, it will be no wonder if students find it dull and meaningless.

So maybe these 3 “lenses” are worth considering in other lessons as well. Almost any tragic topic in history can be similarly addressed – Indian removal, the later Indian wars, slavery, lynching, war.

Questions to launch inquiry

1. Logos: What are the numbers and data on this topic? And how can we present them in a way that will make them meaningful? Try comparing them to your school or community. For example, the same number of people died at the battle of Gettysburg as are in all the schools in our town. Or the number of Japanese Americans sent to internment camps is equal to twice our community. (See “Suggestion #1” of this previous post where I discuss how to visualize statistics).

2. Pathos: How can we humanize the story? Can we find a first-hand account or a short film that describes what this event was like for somebody? Will this account help students feel something? Finding an account from someone near their age can be especially effective, but isn’t always necessary.

3. Ethos: Does this event in history raise ethical issues? Questions about justice, right and wrong, or the rule of law? Is there some way in which the event might have been preventable, or have occurred with better results had the primary actors behaved differently or if different choices had been made? And what do we mean by “better”? And better for whom?

Nothing is inevitable

And yet, isn’t that exactly what we want?

We want to raise young people who are aware of civic life and responsibility, who are thoughtful and some of whom will become our nation’s leaders – and yes, prevent World War III. As the historian Gerda Lerner wrote, in the title essay in Why History Matters: Life and Thought (1997):

The main thing history can teach us is that human actions have consequences and that certain choices, once made, cannot be undone. They foreclose the possibility of making other choices and thus they determine future events.”

Asking ethical questions helps students understand that nothing in history was inevitable. Though events sometimes seem inexorable, that is a rearview mirror perspective.

Next up: the message of the Great Depression

As I prepare myself to teach about the Great Depression next week, I am reminded that economic turmoil led to different outcomes in Russia in 1917 and in Germany in 1933 than in the United States. Our democracy was preserved in the 1930s due to choices made by real people. And roads not taken by others.

Thinking about it that way sounds like a good way to start off my unit (and a way to engage students in a meaningful question following spring break). We will look at statistics: the number of unemployed. We will read first hand accounts of those who experienced poverty and employment. And we will discuss the ethics involved when a government makes itself responsible for the well-being of its citizens.

Love these three lenses!

Lauren, I wished I had had a history teacher like you in school. You care deeply and passionately about your students and how they learn about important and difficult events in history. This is a phenomenal blog; one that I will not only share publicly through Twitter but in a more personal and private way through the work I do as an Executive Function coach. Many of the students I support struggle with writing about history, and your ideas and resources are priceless.

Thank you so much for your comments. Mary, do let me know if you think of other examples for using these 3 lenses. I hope they are useful for lots of topics, not just the Holocaust. And Laurie, thanks so much for your kind words. I hope to be writing another post soon about writing in history class. See my earlier post on this site, https://www.middleweb.com/36391/strategies-to-improve-writing-in-history-class/ which touches on some ideas.