When ‘Math Hate’ Curbs Your Teacher Enthusiasm

A MiddleWeb Blog

I think this time of year invites reflection. You think about what worked and what didn’t. Typically, I spend a lot more time thinking about what didn’t go right than what did. This year in particular has been a challenge. I have struggled with a sense of inadequacy – feeling as if I was failing in many ways.

I think this time of year invites reflection. You think about what worked and what didn’t. Typically, I spend a lot more time thinking about what didn’t go right than what did. This year in particular has been a challenge. I have struggled with a sense of inadequacy – feeling as if I was failing in many ways.

A few months ago, I was talking about this with a coworker after school. I was completely dejected and couldn’t really pinpoint why. I just felt defeated. Well, we talked for awhile, and he said it’s hard teaching a subject kids don’t always like or feel drawn to. That really hit home for me.

I thought about all the times students walked in and asked me what we were doing today, and when I told them, they weren’t excited at all. Or all those times I worked hours and hours on a lesson and students just didn’t get into it like I thought they would.

I have always enjoyed looking for new lesson ideas and planning activities, but I began to dread even doing that. The voice in my head said, “Why bother? They won’t like it anyway.” Even worse are the times students asked, “Are we doing anything interesting today?”

I had thought a lot about how to combat students’ negative attitudes toward math, but I never thought about how their attitudes might be affecting me. It got to the point that I began to steel myself for the negative comments. Every time a student made a negative comment about math, my enthusiasm took a hit.

I have great students – some of them love math and even the ones who don’t will usually try their best for me. But the constant comments that “I don’t like this stuff,” or “it’s boring,” or “I’ll never understand it,” etc., can take their toll.

The negativity doesn’t stop with students either. Many times when calling home to a parent, I hear exactly the same thing. And sadly, even when talking to other teachers it’s not uncommon to hear “math bashing.”

I’m aware that all teachers work very hard under specific challenges. I don’t think any subject has an easier time. I do think that teachers work under different challenges. It would be unrealistic to think that math teachers would be immune to those comments made by students, parents, and others.

To be clear, I’m not blaming anyone. It’s my job to help students overcome their negative feelings toward math. But I had to face up to the truth: the negative comments were taking a toll, and I needed to do something so that I wouldn’t become dejected. Once I realized what was bothering me, I was able to address it and my outlook improved.

Finding the way back

Over the course of the last few months I have slowly begun to feel better, more positive, with more of the teaching enthusiasm that I had lost. I’m not sure that what worked for me will work for anyone else, but I will share what helped:

Talk to a colleague. They know what you are going through (especially those who teach or have taught your subject) and can offer words of support.

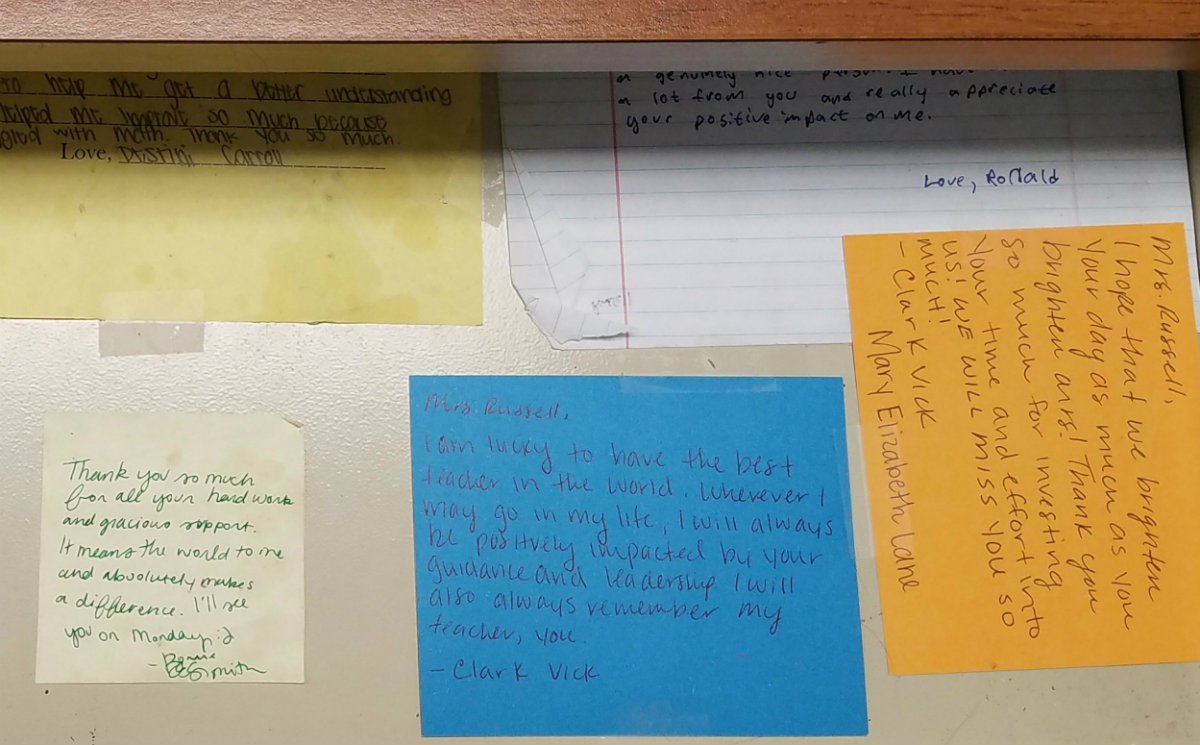

This too shall pass. Realize these feelings are not permanent. They often come as the end of the year approaches. We’re tired; we need a break. You will regain your enthusiasm. If any students in the past have left nice notes with words of encouragement, read them again. They will remind you of why you teach. I have a couple of mine taped to the bottom of my desk drawer so I can see them when I pull it open.

Try not to take negative comments about math personally. Many times students don’t actually mean it, and with time, maybe we can change their minds. Also, I have found it helpful to address it (in a nice way) when a student makes a negative comment about math. Many times when I ask them why they say they don’t like math, it turns out that it’s more about a bad grade they got or that they just think they are not good at it. It provides an opportunity to learn more about the student.

See past what the students are saying and understand why they are saying it. I think a lot of students say they don’t like math because they are struggling, not because they are absolutely opposed to studying it. This article by Ben Orlin helped me understand some of the behaviors of struggling math students.

Attend professional development that you personally find exciting, interesting, and worthwhile. Recently, I was lucky enough to be able to attend a three-day professional development experience with other math teachers. I left feeling re-energized and excited after spending so much “quality time” with other teachers who absolutely get it.

I won’t say that I feel completely back to my old self, but I do feel more hopeful. In fact, one of my classes told me last week that they appreciated how enthusiastic I was about math, and it helped them persist when they saw how much I enjoy it.

Now it’s time to start planning for next year!

Summer reading: Teacher Jessica Lahey’s Atlantic article, “Teaching Math to People Who Think They Hate It,” tells the story of a math professor at Cornell who’s developed some clever ways to interest English majors and other “math haters” in our subject! Can middle and high school teachers find some ideas here?

Michelle,

Thank you for your thoughtful article.

I’m constantly intrigued by the question “When will I ever use this?” And especially when a parent uses this same line rhetorically to defend a child’s distaste for mathematics (or a low grade).

Do literature students ask when they will ever use Hamlet in life? Or does a high schooler stop his biology teacher in the middle of a lesson to ask her when he is going to use a Punnett square in real life?

Keep up the good work.

Thanks for your comment! I feel the same way when students ask me when they are going to use this in their “real life”. I’m not sure why it comes up in math more than other subjects. I guess that’s the challenge math teachers face! Thanks again for the comment!

Thank you for writing this. I have been feeling the same way this school year. Our students received one to one chrome books this year and it has its positives and negatives. It makes some things easier but I’ve been feeling that I need to be their entertainment instead of their teacher. Math takes practice, and at times it’s rather mundane, but necessary. With students being constantly stimulated with technology, math becomes boring…and this generation doesn’t understand that “boring” can bring about creativity and fresh perspective. It’s been an uphill battle. This article allows me to know I’m not alone!

Thank you for your comment! I couldn’t agree more- you said it much better than I could! My students also have Chromebooks and I feel like I am competing with what they have available on their Chromebooks for their attention. That can be exhausting. It was really a source of discouragement for me this year. I think my challenge for next year is to get my students to really buy into the idea that if they will do the hard work (sometimes boring) up front it will pay off later in more interesting ways. I love what you said about how boring can bring about creativity- I’d love to share that with my students next year! Thanks again!

The issue is that Math is a subject quite unlike other subjects. It is concept heavy & information light. Even skills in Math require understanding of underlying concepts.

Unfortunately students have never been taught to “understand” concepts. THis is critical particularly in K-5 when students developmentally cannot handle concepts. Abstract concepts need to be “mirrored” with manipulatives & role plays. In the absence of these, students drown in “non understanding” and develop math phobia.

I have written many articles on this topic which cannot be copied here. But in essence they strategies are

1. Mirror concepts with materials & activities

2. Tell them that only a small part of math, which is K5 curriculum is directly usable in life. Most math is to develop the ability to think logically. An idea of this can be given to students through simple puzzles.

One such activity – “Using all numbers from 1 to 9, make three 3 digit numbers such that their total is maximum”. This has concepts applicable from Grades 3 to 9!

The real solution is to improve quality of teaching in K5, so that students are ready to build on their previous understandings.

I can share more articles on this issue, if you send me your email ids.

I am glad I found this post. It allowed me to see that I am not the only teacher who receives the “I hate math” comments. Math is such an important subject and something students will need to know how to use their whole life. I feel as though one of the biggest problems we encounter now with math is how much we are trying to “make” our students know each year. The more content students are expected to know, the less time there is to spend on practice and mastery. “We will visit this again.” I hear this a lot. If students do not get the opportunity to master a topic before moving on, the foundational skills are weak. What happens if the foundation of a house is weak? It will fail.