Regie Routman: On the Level with Leveled Books

By Regie Routman

By Regie Routman

To level, or not to level? Like many educational dilemmas there is no simple right or wrong answer. Freedom to read and choose what to read is at the heart of our democracy and what it means to be a reader.

What is not in question, I believe, is that we want all students to read because they love to read for pleasure and information, not because they want to move to a higher book level. Here’s the crucial question, then, we need to be asking: How are leveled texts supporting students to become engaged, deeply comprehending, joyful readers?

Full disclosure: I have been “leveling” books for 30 years. With other teachers I have organized by approximate levels of difficulty, multiple copies of high quality fiction and nonfiction books.

Those leveled books serve primarily as a teacher-directed, temporary scaffold for instructing beginning readers in guided reading groups. They are not used as a single determining factor for assessing a reader, and they are not part of the classroom library where students self-select books to read on their own.

Leveled Books Used Successfully

In the mid-1980’s I wrote a proposal to flood a first grade classroom with authentic children’s literature and teach reading and writing through natural language texts, both professionally written and student authored.

Because most of the students in the high poverty school where I was working as a reading specialist were failing to learn to read with commercial reading programs, the superintendent and school principal gave their approval. That journey, including our unique “leveled” book collection, was chronicled in my first book, Transitions: From Literature to Literacy. (Heinemann, 1988.)

While leveled texts played an important and limited role in that successful journey, it was leveling done in a commonsense way that honored the best of children’s literature in combination with students’ choices, interests, and needs as well as thoughtful teacher judgment.

Ultimately we put together an extensive book room for our school where teachers signed out sets of engaging books to be used for guided reading, book clubs, and discussion. For “Beginning Readers” we had a collection of “Rhyme, Rhythm, and Repetition” books and “Predictability and High Interest” books. I wrote at that time (1988):

At no time do we ever state that a student is on ‘green level’ and is to choose green level books. These levels are to be used as a starting point guide only. It is not the list. When we find a book does not work at one level, we change it. Teachers need to make adjustments according to their students’ reactions.”

By grade 3, at the latest, our book collections were mostly multiple copies of outstanding fiction and nonfiction literature, organized roughly by grade levels for small group reading and conversations, sometimes guided by the teacher and sometimes self-directed by students.

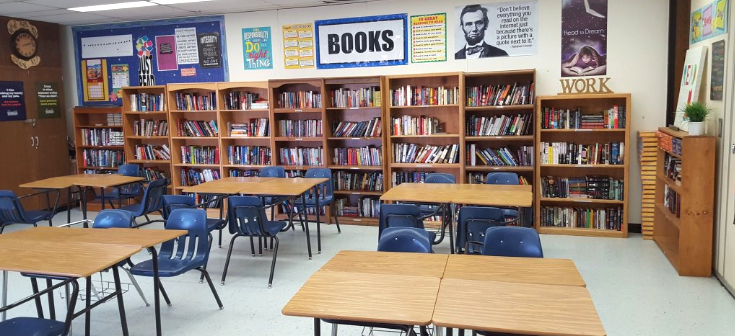

Most importantly the foundational anchor for students becoming readers was the classroom library, which like public libraries everywhere honored students’ choices and was not leveled. The extensive class library – organized with students – and the cozy, adjacent reading area became the centerpiece and heartbeat of the classroom.

It was here the whole class enthusiastically gathered “unleveled” for daily read alouds, teacher demonstrations, shared reading, and shared writing. Most important, daily independent reading – with students reading books of their choice from the classroom or school library – and writing stories, nonfiction and fiction, became the mainstay and first priority of the literacy “program.”

The results were transformative. According to standardized test results, we went from a school where more than 50% of first graders were failing to learn to read to a school where 90% of students became successful, self-directed readers, and those gains were sustained.

Concerns About Leveled Texts

So while there is a rightful and temporary place for leveled texts in guided reading and for helping those few students who are not able yet to choose books on their own, there is an accompanying inconvenient truth: It is possible for students to move through levels without adequately understanding what they are reading.

Because the questions on computerized tests, which often accompany leveled collections, are typically low-level ones, students with just a cursory grasp of a text can do well enough to move up a level. I know that as fact. I failed the computerized test on Charlotte’s Web, a book I love and deeply comprehend, because I couldn’t remember unimportant details. There were no questions on weighty things like theme, setting, character development, or what it means to be a friend.

Here are some other major concerns with using leveled texts:

- Leveling texts is a subjective process.

There is no scientifically proven, research-based process for “accurately” leveling books. Keep in mind the wise statements by scholars and practitioners:

“Students can read texts with comprehension in a range of levels, not one hard and fast level.” (Rita Platt, MiddleWeb blog, “Don’t Throw Out Your Leveled Library Yet!”, Jan. 21, 2018)

“Reading levels are not the same as reading needs.” (Kath Glasswell and Michael Ford, “Let’s Start Leveling about Leveling”, Language Arts, NCTE, Jan. 2011, p. 209)

“Leveling takes a complex idea and makes it too simple.” (Glasswell and Ford, p. 209)

- Over relying on leveled texts can work against developing self-directed, engaged readers.

When the teacher is in charge of the decision-making, student choice and freedom to choose – reading motivators at all levels – are removed or delayed. Some students become hyper-aware of their level, thereby constraining that student’s understanding of what it means to be a reader.

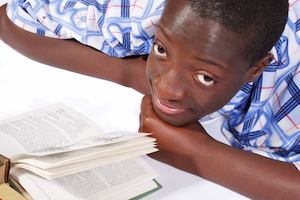

- Leveling is an equity issue.

In some schools, librarians and teachers are only allowed to have students check out books “on their reading level,” which can send a harmful message to students. Restricting students to a leveled reader may underestimate students’ potential, lower expectations, stifle curiosity, and work against perseverance. Also we must ask: Whose interests are being best served? Is it the students, or is it the publishers and those in power?

Recommendations for Great Reading

1. Do not underestimate curiosity, passion and interest as a motivator for turning kids into readers.

Many successful readers who were labeled “dyslexic,” including such notables as Albert Einstein and Nelson Rockefeller, admit to feeling driven to become readers because of their passion, persistence, and patience to read things they were fascinated by but could not yet understand. Limiting kids to levels can kill an eager learner’s natural curiosity on a topic.

2. Organize all classroom and school libraries like the public library, with no leveled books and no areas off limits to readers.

Freedom to choose books and to read them at leisure is the cornerstone of what a library offers – the opportunity to decide for yourself what books you want to read and check out.That means we need to teach students right from the start how to make appropriate choices. Those choices must include – to name several factors beyond word recognition and comprehension – the right to explore, peruse and skim books that appeal; reread easy books; spend months on a series or genre; listen to audiobooks, and abandon books not to our liking.

3. Use leveled books in moderation and with caution.

Ultimately the first graders in the opening story became proficient, joyful readers, not primarily because we used wonderful literature “at their level” for guided reading, but because we kept our main focus on the reading-writing connection and sustained time each day to read and write continuous and relevant texts, mostly of their own choosing.

4. Use common sense; look carefully at what you do as a reader.

5. Use multiple sources of data to assess readers.

First of all, there is no substitute for the informed judgment of a teacher who knows the whole child and knows, as well, that a reading level cannot sufficiently represent a reader. We must also consider volume of reading, reading interests, motivation, anecdotal evidence from discussions, conferences and observations, student self-assessments and reflections, and more.

Finally, all students deserve the chance to read what they want. It’s a lesson I learned over 30 years ago, and it’s the opening story I tell in Transitions. When a group of second graders begged me to let them read an enchanting book I’d read aloud to them, I told them “This book is too hard for you.” The children, as children do, persisted and I finally relented.

To my amazement at the time, I learned that when interest and motivation are high enough, with guidance and practice students can often read in context what tests and levels indicate they cannot. Let’s ensure that however we teach any reader, we keep engagement, excellence, equity, and joy at the forefront.

______________________________________________

Regie’s most recent book, The Heart-Centered Teacher: Restoring Hope, Joy and Possibility in Uncertain Times, is published by Routledge/Eye on Education (2024).

For more information about her work and her many books and resources, see www.regieroutman.org.

Thank you for sharing all these angles and ways of thinking about reading levels. Giving pause to think about purpose and value where reading levels are concerned is such an important topic. It is a conversation that I hope continues and I throw my coin in the wishing well to ask that all teachers wonder a little longer about their purpose and value of reading levels as a teaching tool. Many thanks and best wishes.

Thanks for this kind response Betsy. Like all excellent teaching, there is no one “right” way. I agree that we need to think more about purpose and value, not just with reading levels as a teaching tool, but with all the teaching and assessing tools we use.

Regie, you always amaze me. One of the things that makes me weary is the dogmatism in education. So much of what I read on Twitter and in blogs makes the answers to edu-questions seem black or white. You know, “Levels BAD!” or “Levels GOOD!” But, in my experience, most often the truth is less binary. I appreciate your willingness to be thoughtful and open and to dig deep and look at issues like using leveled text with a, well, a level head!

Thank you for sharing my thoughts in your piece. I believe that there is a place for leveled texts in the learning environment and that they can be used (especially in the early to mid-elementary grades) to a strong positive effect in terms of academic growth – building student confidence a sense of self-efficacy, and the passion for and love of reading. As you said, the goal should be to help students learn to pick books they will love so that they read, read, read!

Great post, Regie. Thank you!

Thanks for your thoughtful comments, Rita. As you note, too often educators take a rigid stand on an educational issue, and it’s rarely the case that works out well for us or our students. If we keep what’s truly “best” for students uppermost in our planning, teaching, and assessing, we’re more likely to adapt nuanced, principled, and equitable stances on tough issues.

This is a great post Regie, but I worry when educational leaders such as yourself place an emphasis on classroom libraries and the use of external consultants when this type of issue could be solved on a much larger scale by supporting and promoting school libraries let by a trained teacher librarian. The combination of centralised and decentralised resources is so much more powerful than needing to rely on individual teachers and classrooms.

I appreciate your thoughts Nadine. I believe the school library is of primary importance, staffed by a knowledgeable teacher librarian who works in concert with classroom teachers and their students. I champion school librarians! The classroom library is essential for all students’ immediate and equitable access to a collection they’ve helped organize according to their interests. Excellent school, classroom, and public libraries are all essential!