Science Fair Projects or STEM Team Events?

A MiddleWeb Blog

Think back to your experience as a student. What purpose would say your science fair project served?

What about as a teacher – what do these projects accomplish for your kids? Or as a parent? Were you one of the many parents who felt science projects required too much time, caused a lot of stress, and didn’t achieve their purpose?

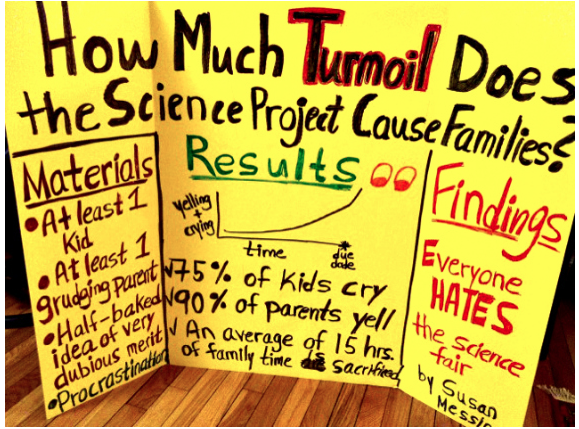

In researching this post, I found an article End the Torture of Science Fairs by Liza Rickey on the Teaching Channel. Liza refers to this hilarious article by Susan Messina, creator of what’s being loosely referred to as “the turmoil project.” I loved both articles!

So, back to science fair projects. The scientific method was a process by which mankind climbed into the age of reason and began to think differently about our physical world. Using this method helps students understand how scientific knowledge develops and gives them an appreciation of the approaches scientists use to investigate, model, and explain the world. Science projects have traditionally been proposed as one way to introduce the scientific method.

Ups & Downs of Science Fair Projects

If a science fair project is properly done, kids should be able to follow a series of steps and discover answers for specific questions they have. The usual steps look more or less like this: (Check out a more detailed version of this Science Fair Project Guide from Science Buddies.)

The Question. Start with a question built on curiosity.

Background Research. Investigate information pertaining to the question.

Hypothesis. Make an informed, justifiable guess about the possible answer to the question.

Experiment. Devise and conduct a carefully designed, controlled, and replicable experiment.

Observations and Analysis. If data prove the hypothesis correct, the question has been answered. If the data does not prove the hypotheses, more research and testing is needed.

Conclusions. Summarize and explain the results, including possibilities for future study.

Communication. Write a final report and display data analysis, observations, and conclusions.

Sounds logical, but here’s the rub. According to STEM Teaching Tools.org, following this rigid step-by-step “scientific method” does not truly introduce kids to the complex ways scientists think and work.

Think about the issue of time related to science fairs. I never taught fewer than 150 middle school students per day, and each student was doing his/her own project. Each one had to understand how to choose a good, testable question and be able to effectively set up controlled experiments with dependent and independent variables.

Given that I had to regularly monitor and coach individual students to keep them on track, quite a slice of time came out of teaching the curriculum objectives for the quarter (which sadly usually had nothing to do with science fair projects anyway).

Competition and equity. Then the equity issue always came up. Science fairs were competitive events. Some kids had parents who could (and would) buy them everything they needed for their projects. These parents usually provided major assistance with the project itself. Other students had few resources, even less support, and started in different places in terms of science readiness. My students were unable to compete on equal footing, which generally led to the same students experiencing success or lack of success over and over.

Research by Grinnell et al. suggests that adolescents don’t necessarily care for competition of the kind science fairs present, and that competitive science fairs might even hinder student learning. Not winning, or getting negative feedback on effort, can stymie kids’ interest.

Other logistics issues. In my experience, science fair projects were often “loner” projects that kids worked on out of school. The annual science fair was time-consuming, space-consuming, and generally fell short of producing learning, excitement, and enjoyment in students (and certainly in parents).

Science fairs also fell short of my hopes in terms of academic benefits for students. And I’m not alone. There’s a growing sense among scientists and educators that many science fairs simply aren’t doing a good job at helping kids learn about (or become engrossed in) science. (Schank)

Enter: The STEM Solution

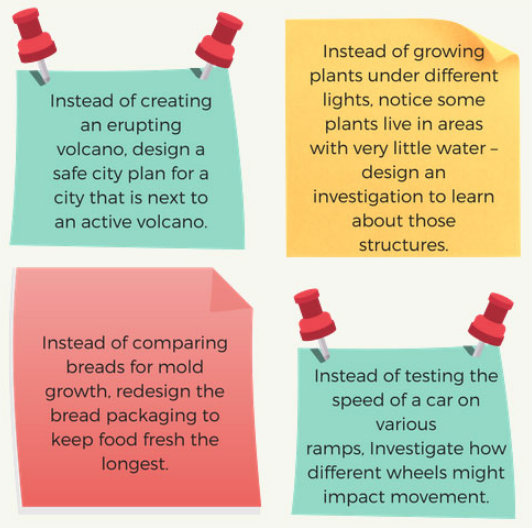

Good news! Increasingly schools are experimenting with some fundamental changes that show promise for better opportunities to practice real science. The new push is for STEM fairs – fairs that involve students in integrating science, math and engineering practices in authentic and relevant ways. STEM projects involve teams of kids in a hands-on process for solving real problems.

To help clarify STEM, the National Research Council identifies eight core practices of science and engineering that all students must be able to do. These are a dynamic set of building blocks for student investigations, and they are aligned and intertwined at each level.

- Define a real problem.

- Develop and use models or prototypes.

- Plan and carry out investigations.

- Analyze and interpret data.

- Use mathematics and computational thinking.

- Design solutions.

- Engage in argument from evidence.

- Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information.

A thorough explanatory chart distinguishing practices in science from those in engineering are on pages 49-53 of this free online publication by the National Academies Press. This is one of my favorite “go to” articles to keep my STEM thinking straight.

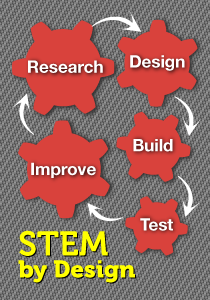

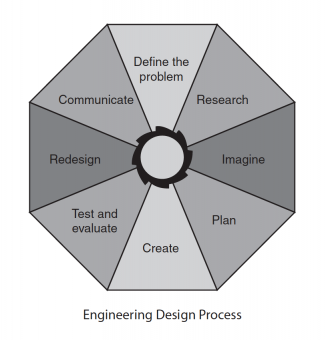

Since all kids need these competencies, this set of eight core practices drives the purpose and focus of a STEM fair. As STEM teams work to come up with a solution for a problem, their thinking is guided by the engineering design process. Unlike the scientific method, this process is iterative . . . not linear, meaning that students may go back and forth between steps of this engineering design process as many times as needed to find the best solution.

There’s also an EDP Description for Teachers you may use. Hey – just look around the website and if any of the tools or information I’ve posted help you, your students, or others – go for it! That’s why I posted them.

Match-up: STEM vs. Science Project Fairs

STEM fairs overcome several problems I encountered staging science fairs. Since I have worked with both kinds, here are some of my takeaways.

- Students work in collaborative teams. That means a teacher may coach 4 to 6 teams per class rather than working with 30 individual students. (FYI – This document can help you with student teaming.)

- STEM projects are more inclusive of all students and minimize equity issues. Resources can be shared and made more available to all students.

- STEM projects can remove the competition aspect. They can promote broader student involvement and more enjoyable learning during the project. They focus on collaboration for finding solutions.

- Students often work on their STEM projects during science/math/ STEM class (or all three). Kids can learn the basic practices of STEM and get help to keep them on the right track over the course of their school day.

- The quality of a team’s STEM project is determined by the degree to which students are mastering the process for solving a problem. STEM projects engage kids in a real-world approach to problem-solving. Their grasp of the method is the most important aspect of the project.

Science Fair or STEM Fair?

To make the decision between science fair and STEM fair, figure out what you want your students to get out of the experience. What value should this experience have for them? Then begin to design your fair to build those practices and learning skills in your students.

Feature image: Liza Rickey

________________________________________________