Feedback That Saves Time, Improves Writing

One of my deepest regrets about my teaching career is how much time I wasted on grading papers. I lost literally months of my life—weeknights and entire weekends swallowed whole—to the process of copy-editing student essays.

My life was often imbalanced and exhausting, but even worse: all of this work did not improve my students’ writing.

Various factors influence students’ responsiveness to comments on their writing: 1) whether or not they can revise the work; 2) whether or not they understand the comments and how to act upon them; and 3) how long it’s been since they wrote the piece. Waiting two weeks to give extensive editing/revision comments that students cannot act upon is a recipe for indifference.

For this reason, feedback must be timely and strategic. And it’s easier to give quick feedback if students are doing the work in manageable bites. If you wait until they’ve written an entire essay, it’s too late.

Drafting in chunks means they won’t go too far afield before you redirect them. Nothing contributes to student disaffection with writing more than being told after they have written an entire essay that they need to rewrite the whole thing.

Feedback can be provided in several ways:

- Through teacher-led mini-lessons,

- Through teacher-student conferences, or

- Through a partner feedback protocol.

Let’s take a look at each option.

Teacher-led Mini-lessons

One of my favorite techniques for revising/editing mini-lessons is what Doug Lemov calls “Show Call.” The teacher selects student writing to share with the class by projecting it with a document camera and asks the class for input on what is effective and what can be improved.[1] What I particularly love about this technique is that it builds accountability for written work.

When students know that their writing might be shared with the whole class – whether for praise or constructive feedback or ideally both – they tend to pay more attention to the quality of their work. Norming the class to expect this approach establishes the expectation that good writing can always be improved.

Whether you select student work while actively monitoring[2] the class or while sorting through drafts afterwards, Show Call enables you to provide targeted feedback on points that benefit more than one student. PS: Make sure you seal the deal at the end of the mini-lesson.

My friend Katy Wischow, a writing consultant who observes classes frequently, notes: “A lot of teachers are on board with using student writing in lessons, but beyond asking for input, they’re not sure what to do next – so it kind of fizzles out, into a ‘Well, there you go’ sort of an ending.”[3]

Instead of “Well, there you go,” give students explicit directions, such as “Look at your own work now and ask yourself the same questions we just asked about these examples. Then do what you need to do.”

Timely Writing Conferences

By contrast, writing conferences obviously have a more limited audience. But your feedback should still be targeted. One reason teachers hesitate to confer with students is that they worry about how much time conferences take. Here are some ways to save time:

► Before you launch conferences, tell the class what you plan to focus on (e.g., “I’m just looking at your first body paragraph to see how effectively you’ve provided context and explanation for your evidence!”).

► Direct students to star or underline what you want to look at (e.g., “Please underline the topic sentence in your first body paragraph!”) before they meet with you.

► Call three students up to meet with you at the same time. Give them quick feedback one by one, noting, “Stay here and work on that; I’ll come back to you in a few minutes.” This approach—much like when you’re in the Post Office and the clerk tells you to step aside but stay at the counter to finish taping your package so you won’t have to wait in line again—has several benefits:

– First, it offers accountability with support: Students begin working on revisions avidly, knowing you will circle back; and it eases their anxiety to know that if they have any questions, you’re right there to help.

– Second, it enables you to capitalize on students’ inherent nosiness: While waiting for their turn, they can “academically eavesdrop” and learn from the feedback that their peers receive.

– Third, it offers flexibility: If several students require the same coaching, you can spontaneously conduct a small-group mini-lesson instead.

Here are some additional points to consider when you’re conferencing:

Here are some additional points to consider when you’re conferencing:

- Remember to start your comments with at least one bit of specific praise (even if you have to say something hedgy like, “I like what you’re trying to do here”) and maintain an upbeat, appreciative tone to open their ears to whatever else you might need to say. When students become defensive, you may lose precious time trying to convince them to listen. And an instructional compliment is powerful in and of itself, not just to forestall defensiveness. Naming a specific positive thing that students are doing means they will repeat it (and they might have just done it by accident, so now they know it’s a real thing!).

- Try to frame your feedback in the form of questions instead of judgmental statements: “Can you clarify what you meant here?” will be received more easily than “This part confused me,” or “I don’t understand this sentence.”

- When a student’s writing is garbled, it helps to ask, “What were you trying to say here? Just tell me.” Often students can explain their ideas more effectively orally, and then you can say, “OK, that sounds good. Let’s write that down.”

- You may want to ask students to read their own work aloud so you can praise them as they go and so they can catch their own errors, especially punctuation problems. You can prompt them with this: “When you read this part, see if you pause, or if you stop. Then we can decide what to do with punctuation.”

- Avoid specific corrections such as “You need a semi-colon here” because that kind of advice doesn’t teach students anything. Instead, provide grammatical context and ask a question to see if students can figure out how to make their own corrections. For example: “You have two independent clauses—two complete sentences—separated only by a comma. So right now it’s a run-on. What do you need to do to make this work?” If the student appears stumped, offer options: “You could add a conjunction after the comma, you could replace the comma with a semi-colon (if you think the sentences are closely related), or you could break this into two separate sentences. Which do you want to do?”

Partner Feedback Protocol

Along these same lines, when it comes to peer feedback, be careful. Instead of “peer editing,” which is often a recipe for the blind leading the blind (“I think you need a comma there, but I’m not really sure”), students should take turns reading aloud their essays or narratives while their partners read along and pause to tap the desk twice (with two fingers or a pencil, to avoid cacophony) any time they have a question or a specific sentence or phrase to praise.[4]

The writers should pause to listen and make notes, but not respond orally because we don’t want students to negotiate over the revisions (they might never get through the essay!); the writers will consult their notes and revise later.

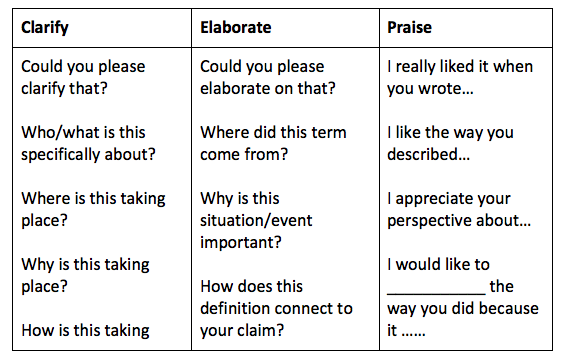

This simple feedback can be powerful. Authentic praise is useful and motivating. The questions can be either a request for clarification (“Could you please clarify that?”) or something more precise such as “Could you please clarify what you meant by ‘Scout should have realized that’?”) or a request for elaboration (“Could you please elaborate on that?” or “Could you say more about why you think Ponyboy did that?”).

Questions along these two lines—as opposed to statements such as “That’s confusing,” which can raise defensive hackles—show that the reader is genuinely interested. More importantly, they also invite the writer to explain. Which is what good writers do. Relentlessly.

A couple of bonus notes:

- It’s crucial to role-play this partner feedback protocol. Then invite students to share what they think could be challenging about using this approach. Do some preemptive troubleshooting. It’s time well spent.

- After students practice a few times, ask them to evaluate their feedback: “What went well? What do you need to work on?” Some of your strongest students might struggle because they are so eager to offer advice. And although it’s tempting to answer the questions immediately, the writers should limit themselves to taking notes.

- See the chart below, designed by several teachers at Great Oaks Legacy Charter School in Newark to support middle school students using this protocol.[5]

Time Saved. Writing Improved.

These three approaches engage students in improving their writing, and their writing actually does improve. Once the drafting and revision process is complete, you can collect the final drafts and—using a straightforward rubric*—grade them in a tenth of the time. Then go out for a peaceful walk.

*See the ESSAY WRITING RUBRIC and PARAGRAPH RESPONSE CHECKLIST.

Notes

[1] Doug Lemov, Teach Like a Champion 2.0: 62 Techniques That Put Students on the Path to College (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2015). For a detailed description of “Show Call,” see 290-299. Another great Lemov resource on this topic of feedback is his TLAC blog post “Reducing Teacher Workload by Re-thinking Marking” which draws on a visit he made to a large high school in London. It’s a deeper dive into the mistake of “maximum effort; minimum impact.”

[2] I prefer the term “active monitoring” over Paul Bambrick-Santoyo’s “aggressive monitoring,” which to me sounds a bit hostile (See Paul Bambrick-Santoyo, Get Better Faster: A 90-Day Plan for Coaching New Teachers [San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2016], 43).

[3] Katy Wischow, Email to the author, February 18, 2018.

[4] This section draws from my MiddleWeb post “Shared Reading Needs to Have a Clear Purpose,” Jan. 8, 2018.

[5] Shout-outs to teachers Bianca Licata and Allison Paludi for this chart, which I have modified slightly.

____________________________

Sarah consults with schools on literacy instruction, curriculum development, data-driven instruction, and school culture building. She taught English and Humanities in both suburban and urban public schools, including the high-performing North Star Academy Charter School of Newark. For more information visit her website The Literacy Cookbook and her TLC Blog.

Here are some additional points to consider when you’re conferencing:

Here are some additional points to consider when you’re conferencing: