Teaching Poetry for Social Justice

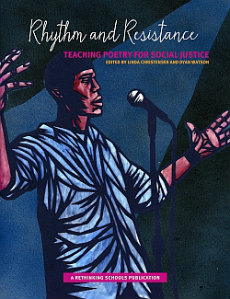

Rhythm and Resistance: Teaching Poetry for Social Justice

Edited by Linda Christensen and Dyan Watson

(Rethinking Schools, 2015 – Learn more)

Linda Christensen and Dyan Watson’s Rhythm and Resistance: Teaching Poetry for Social Justice had me at its title, which promises the perfect blend of art and activism.

After I read the introduction to the first chapter, I realized this book might promise even more than that. Christensen and Watson “believe that poetry is for everyone” and suggest that the lessons in the book “teach students that they are poets.”

They end their brief preface with a quotation from poet William Stafford that made me sit up and want to create:

If I am to keep writing, I cannot bother to insist on high standards… I am following a process that leads so wildly and originally into new territory that no judgment can at the moment be made about values, significance, and so on… I am headlong to discover.

Each chapter feels complete on its own – easy to look over as you begin a unit – or you could read the book start to finish for a compendium of ideas to draw upon all year. The book’s dozens of lessons include reflective explanations of how they came to be, along with many models by professional and student poets.

Snapshots of Voice and Conscience

In a short review it is impossible to encompass the myriad of teaching strategies in Rhythm and Resistance, so here’s a snapshot from each chapter to give a sense of the book’s scope.

Chapter 1

Roots: Where we’re from

In Renee Watson’s lesson about identity, “Talking Back to the World: Turning poetic lines into visual poetry,” she asks students to “create self-portraits using the strongest lines” from poems they’ve created about their true selves. When she hung the portraits on the wall for an open mic event, parents, students and teachers “stood at the wall learning and relearning the young people we thought we knew. Together we saw them again, for the first time.”

Chapter 2

Celebrations: Lift every voice and sing

Linda Christensen, whose thoughtful lessons weave throughout the book, supports positive self-talk in “Praise Poems: Celebrating and back talking.” After reading texts by poets such as Lucille Clifton, Maya Angelou and Lawson Fusao Inada, and Naomi Shihab Nye, Christensen asks her students to “praise their own attributes that often have been overlooked or held in contempt by society” — a powerful way to “speak against the negative portrayals of race, language, gender, sexual orientation, and size” that her students often encounter. Through celebrating unexpected attributes, such as with the “big women” Clifton and Angelou describe, students also give themselves a perhaps unexpected voice.

Chapter 3

Poetry of the People: Breathing life into literary and historical characters

As a teacher of both English and history, I loved this section’s insistence on the need for students to develop empathy through studying the past. Dyan Watson assigns a “dialogue poem” between two very different historical voices, such as the perspective of a U.S. soldier fighting during the Vietnam War and that of a man whose daughter the soldier killed. Such a juxtaposition emphasizes the disparity between those with power and means, and those without.

Watson also makes the case for bringing poetry into history: “When the world was chopped up and put into different curricular boxes, poetry ended up in the box labeled language arts. But poetry ‘belongs’ every bit as much to social studies…. It’s one important way we help students recognize that social studies is more than dates to memorize; it’s about lives to learn and to care about.”

Chapter 4

Standing Up in Troubled Times: Creating a culture of conscience

One especially topical lesson in this high-energy chapter on activism is Renee Watson’s “Happening Yesterday, Happened Tomorrow: Teaching the ongoing murders of black men.” After reading Willie Perdomo’s poem “Forty-One Bullets Off-Broadway,” students write their own tribute to black men such as Oscar Grant or Trayvon Martin. This assignment seems like a perfect pairing with Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give, the award-winning young adult novel about the Black Lives Matter movement.

Chapter 5

Turning Pain Into Power

This chapter aims to transform students’ difficulties into strengths. In Tom McKenna’s lesson “Pain and Poetry: Facing our fears,” Raymond Carver’s poem “Fear” becomes the basis for student poems about their own fears. Writing down individual worries shows students that they share many of them with their classmates. I could see how this lesson could help discussions of current events in my own eighth-grade classroom focus on taking action rather than becoming derailed by rumbling worries.

Chapter 6

The Craft of Poetry

This chapter goes deep into word choice and revision, with lessons on strong verbs, repetition, images and the elements of poetry. It ends with Christensen’s description of the read-around, which she calls “the classroom equivalent to quilt making or barn raising.” This activity is a sort of “town square” in which people ask, as one student reflected, “What was it about that piece that made me get all goose-bumpy?” The read-around creates its own sort of community, one that will encourage important issues to rise to the surface.

Unlimited Possibilities

Please don’t take my word for how useful Rhythm and Resistance is! Order it, and you can pick and choose your own ways into students’ identities and impacts.

If every elementary, English and history teacher did even one of these activities each year, our understanding of the children and young adults in our classrooms would deepen immeasurably, as would their appreciation of their families and their communities, both local and global.

As Christensen and Watson insist in the last chapter, “We believe that teachers must offer poetry not as a dried-up unit where students study other people’s poetry every April, but as a living, breathing way to understand the world daily…. Students need to care about their writing, and that means that all poetry begins first in a curriculum that matters, that encourages students to grapple with big issues in their families, neighborhoods, and world.”

Sarah Cooper teaches eighth-grade U.S. history and is dean of studies at Flintridge Preparatory School in La Canada, California, where she has also taught English Language Arts. She is the author of Making History Mine (Stenhouse, 2009) and Creating Citizens: Teaching Civics and Current Events in the History Classroom (Routledge/MiddleWeb, 2017). She presents at conferences and writes for a variety of educational sites. You can find all of Sarah’s writing at sarahjcooper.com.