My Must-Listen Podcast: Teaching Hard History

A MiddleWeb Blog

For a long time I had what I thought were good reasons: I don’t commute far. I like to listen to music, not words, while I exercise. I had a wonky old phone without enough memory to download podcasts while doing just about anything else.

But this past summer I became a podcast convert. Circumstances changed. I was driving my kids to far-flung camps and got tired of the radio and even Bruce Springsteen (only temporarily, don’t worry!). Sometimes I wanted to chew on new topics while I worked out. And I finally got a phone that can handle seemingly infinite episode downloads.

As a result, my world has opened up, because listening to a podcast rather than reading feels like getting away with something grand.

So I’ve been loving a lot of shows you might also be listening to: Malcolm Gladwell’s Revisionist History, Radiolab’s More Perfect, Jennifer Gonzalez’s Cult of Pedagogy, Angela Watson’s Truth for Teachers. I’ve even fantasized about starting my own podcast about teaching controversial current events.

A Topic That Hits Hard

Surprisingly, the podcast I’ve turned to over and over is one of the most intense ones to process: Teaching Hard History from Teaching Tolerance at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

I first heard about it from Jennifer Gonzalez’s interview with its host, Hasan Kwame Jeffries, on Cult of Pedagogy.

At first I thought: I know a lot of this stuff already, especially given recent classes on the Civil War, such as Emancipation, that I took online through the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

I know the Civil War was caused by slavery, not states’ rights. I know that Dred Scott v. Sandford was one of the worst decisions in U.S. history. I know that Lincoln’s policies of military emancipation led to legal emancipation.

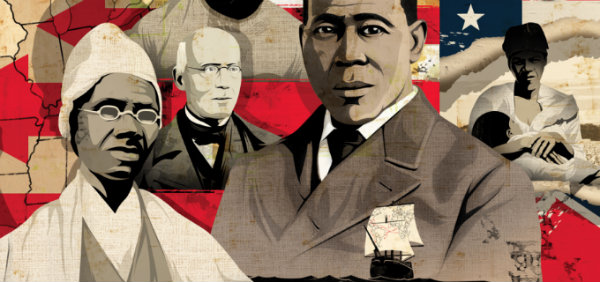

Source: Teaching Hard History

Yet the more I’ve listened, the more I’ve learned, because these podcasts build their arguments steadily and subtly.

In addition, the podcasts are steeped in primary source material we can use with our classes, as are the lessons and primary source documents accompanying them on Teaching Tolerance’s website.

And I enjoy host Hasan Kwame Jeffries’ folksy and personal introductions to each show, sometimes related to his childhood or his time at Morehouse College, each of which has a serious takeaway.

Three “Rewindable” Moments

Here are just a few examples of Teaching Hard History moments that have caused me to hit rewind in the car, to hear them again. Links to all episodes can be found at the Teaching Hard History Podcast site.

In “Dealing With Things As They Are: Creating a Classroom Environment,” Steven Thurston Oliver of Salem State University acknowledges the guilt that students can feel when addressing issues of slavery:

And I find that one thing that’s helpful, particularly for white students, is to lay out for them this idea that we didn’t do this. All of us sitting in a particular classroom, we didn’t do this, we’ve inherited this mess that we find ourselves in…

But what follows that very quickly is this notion that all of us, although we didn’t create these dynamics, we now have a responsibility and an opportunity to consider the ways in which we might be upholding some of these systems of oppression, how we might be benefiting from some of these dynamics, and most importantly, how we can be part of undoing these systems of oppression. I think that laying it out that way helps students wrap their minds around it.

Oliver’s suggestion to acknowledge that we all live with the consequences of the Civil War and its aftermath – and then to insist that we all take our part in improving the world in response – resonates with how I want to teach my classes. I want students not simply to feel mired in tragedy (as can happen all the time when learning U.S. history), but to imagine how they can begin to help.

Source: Teaching Tolerance

A second professor at Salem State, Bethany Jay, offers two episodes on “Slavery and the Civil War.” To begin, she aggregates evidence that slavery was indeed the cause of the Civil War, introducing stories and sources by saying:

No matter where you’re teaching across the United States, if you ask students to name some of the causes of the Civil War or the cause of the Civil War, you’ll most likely hear states’ rights come up. And that’s even in classrooms where students are not at all emotionally attached to the subject of the Civil War…

But … everybody knew the reasons that people were seceding before the Civil War, because the South was very clear about why they were seceding. They were seceding to protect slavery. And the issue of states’ rights was connected to the issue of slavery. So, this is a conversation that has only happened as we’ve historically looked back at the Civil War, whether we’re looking back at it in 1877, in 1954 with Brown v. Board, or in 2018.

Once Jay finishes her methodical historical work, she wraps up by saying:

So now that we’ve done the work of looking at the Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act, looking at this moment of the secession crisis and what the seceded states are saying the reasons for their secession are, we can see how artificial it is when we continue to talk about states’ rights as an issue that is separate from or an alternative to slavery. If we take slaveholders at their word, in their own words, we know that slavery is the reason for secession, and that it’s the preeminent cause of the Civil War.

Again, her use of primary sources, including South Carolina’s “Immediate Causes” and, in her second podcast on emancipation, the First Confiscation Act, shows exactly the kind of work we should be doing with our students. And, because Jay focuses on both history and on teaching history in her university work, she gives ample ideas of how to take advantage of these documents with our classes.

One last presenter I’ve really enjoyed is Paul Finkelman, legal scholar and longtime professor at Albany Law School, with one podcast on “Slavery and the Constitution” and another on “Slavery and the Supreme Court.”

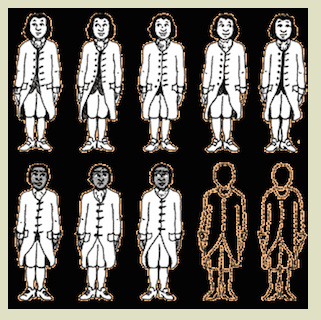

In the first, Finkelman connected the Three-Fifths Clause from the Constitution indelibly to the two major compromises leading to the Civil War, with a clarity I hadn’t thought of before:

If you look at subsequent debates, if you look at the debate over the Missouri Compromise, which allows slavery to spread into Missouri west of the Mississippi, north of where the Ohio River reaches the Mississippi, the Missouri Compromise could not have been passed if the South had not had a significant number of representatives based on counting slaves as three-fifths of the population for representation. Similarly, it’s impossible to imagine in 1850 that the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 could have been passed if there had been no Three-Fifths Clause because the votes weren’t there.

Source: BlackPast.org

In the second episode, Finkelman tells a story about the 1857 inauguration of James Buchanan, Buchanan’s close relationship with Chief Justice Roger Taney, and the strangely timed release of the Dred Scott decision. For that, you’ll have to listen, as he tells it better than I would. But there’s a transcript for each episode at Teaching Tolerance, if you’re in a hurry!

There’s Even More

I haven’t even mentioned other excellent Teaching Hard History episodes, such as “Confronting Hard History at Montpelier” or two parts on “Film and the History of Slavery with Ron Briley.”

Listening to even one of these podcasts, and considering how we can incorporate even one of the documents or stories into our classes, will complicate the history we teach in interesting – and I would argue necessary – ways.

________________________________________