English Learners Need to Use Academic Language

A MiddleWeb Blog

“My kids seem to speak English well, but when it comes to academic tasks, they struggle.”

“My kids seem to speak English well, but when it comes to academic tasks, they struggle.”

We often wonder why English learners have a difficult time with standardized tests and essays in content areas but are able to communicate with peers and get along fairly well on a day-to-day basis.

The reason behind it may be that academic language is different from everyday language. Academic language takes from 5-7 years to acquire while social or conversational language (often known as BICS or ‘basic interpersonal communicative skills’ – coined by Jim Cummins) only takes 2-3 years.

What we know for sure is that students need to make greater gains in academic language in order to become successful in school.

What is academic language?

“Academic language” is the language used to communicate ideas about a specific content area of instruction. It’s the “textbook talk” and the vocabulary and syntax used in lectures and class presentation. It’s not limited to single words but includes phrases and sentences as well. Think about “genre” and “point of view” in ELA classes or “metamorphosis” and “the hydrological cycle” in science.

It is critical that English learners are offered massive opportunities on a daily basis to practice using academic language. Why? We have to consider that some English learners go home to environments where they speak another language in the house. And that is awesome! Bilingualism has many benefits.

However, when they are in our classrooms, we have to build as many opportunities as possible for English language development using domain-specific vocabulary. We have to put the academic language in their mouths.

Other students (including native English speaking students) may go home to English speaking households, but the level of vocabulary or conversation may not be where we’d hope. This is yet another reason why our classrooms need to be filled with opportunities for students to use academic language.

10 tools to support academic language use

How can we get students to use academic language? Here are 10 ways to get students, especially English learners, using academic language in your classroom.

Remember that explicit modeling and explanation of these routines is necessary for success. And I caution you that the first time you try one, it might not go as planned. Don’t give up! Just like cooking something for the first time (at least for me) it may not turn out the way we hope. But with practice and repetition, it gets better!

1. Linguistic Frames. Linguistic frames or sentence frames help English learners with the language structure. They give students the momentum to begin a sentence in English. Many times our students know the answer. They are cognitively capable of answering the question but struggle with putting the thought into an English language structure. Linguistic frames are a scaffold. An example in science might be, “Based on the experiment, I can conclude that…”

2. Conga Line. Students are divided into two lines facing one another (here’s how). The teacher poses a question and students take turns sharing the answer with the partner facing them. When the teacher turns on the music, one of the lines moves down until the music stops. Everyone has a new partner and partners share once again.

The repetition of sharing their answer as well as hearing from multiple partners supports English learners in developing vocabulary by listening and speaking. Some students benefit from a linguistic frame as an additional scaffold.

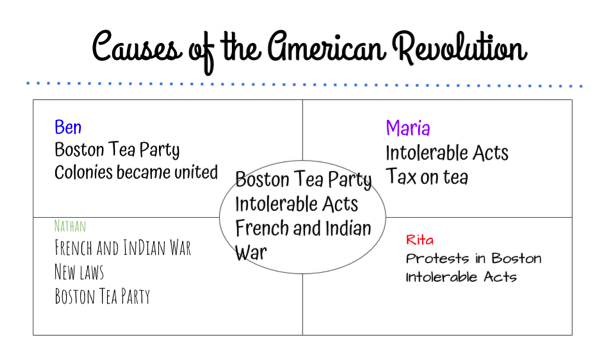

3. Consensus: Students begin by individually brainstorming on a topic or question. Then each person shares with their group. The group looks for trends and similar ideas and writes them in the center of a graphic like the one below.

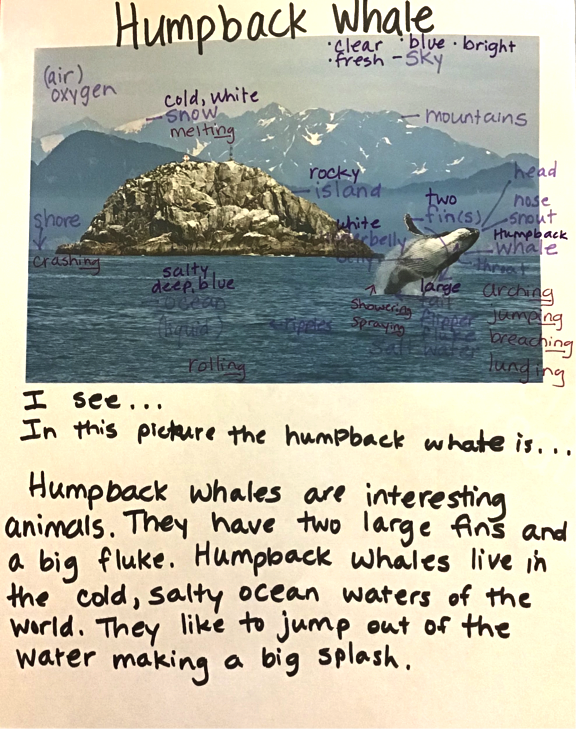

5. Picture Word Inductive Model: Calhoun (1998) presented this method as a way to build vocabulary. Students are given a picture related to the topic of study and are asked to list all the words they know about it. They discuss with a partner or group. Students dictate what they see in the picture as the teacher labels. The teacher adds critical vocabulary and multiple meaning words. Students use the labeled visual to generate verbal and written responses. Linguistic frames can be offered as a scaffold.

6. List, Group, Label: Students are given a LIST of words or asked to brainstorm words together in groups on a given topic of study. Then they work together to arrange the words into categories or GROUPS. Finally, they collaborate to come up with a name or LABEL for each group.

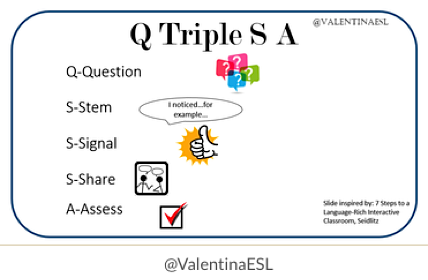

7. QSSSA. Seidlitz and Perryman (2011) offer the QSSSA as a structured conversation strategy that promotes academic language with 100% participation and embeds wait time. The teacher poses an open-ended question to the class. Students are asked to give a signal when they can answer the question. The teacher provides the class with a sentence stem to scaffold academic conversation. Students share their responses with a group or partner. The teacher holds students accountable by assessing a few responses and randomly calling on 3-5 students.

Students benefit from hearing many responses and from repeating and building upon their own responses. Linguistic frames and word walls can be offered to scaffold students.

9. Barrier Games: Students are paired up and sit across from one another with a barrier between them. Each partner holds vocabulary words, visuals, or information in front of them and must explain to the other partner using only verbal language what they have in their hand. The partners must guess.

10. Jigsaw: In the early 1970s, Elliot Aronson invented and developed the jigsaw strategy with his college students. Students are grouped in fours and each assigned a different section to read or task to complete. After reading their assigned section, they meet with others who read the same section to discuss. This is their expert group. The expert group talks about what they read, what was important, and what they will share with their peers that did not read this section. Everyone returns to their original groups of four and each member/expert takes a turn sharing and teaching about their section.

Meeting the challenge

Academic language can be challenging for students and for us as educators. Taking a student centered approach where kids are doing the work means a mind-shift for many of us. When we create spaces where students negotiate for meaning and they build their knowledge with our support and facilitation, greater gains will occur!

Great read. Informative and easy to apply.

Thanks for reading and for your feedback, Jodi.

Teachers are the busiest people on planet earth! Items like these are great blessings!

I agree, Vye. Teachers are extremely busy!! Thank you for your comments. Take care!

Very timely and spot in. Thank you for your ideas!

This is very useful to use during my PLC at my school. Thank you!

Valentina, Wow! Excellent information! I am working on a paper about “academic language” now and it’s interesting to see how different people operationalize this term. Thanks for your information and class ideas. I especially like that it’s written in very accessible language.

Thank you for the feedback, Keith! Good luck on your paper.

Thank you for your dedication to our ELs! Your posts keep me motivated and always inspire me to do more for my students!

So sweet, Rebecca! Thank YOU for your dedication! I know personally how amazing you are! Your campus and students are lucky to have you.

Valentina, do you also teach Tier 2 words and definitions as part of academic language? I’d love to hear more about how to do that with ELLs. Thank you.

Valentina,

I enjoyed reading your post. It gave me great ideas to use in my classroom. I’m hoping to try the Barrier Games and QSSA with the vocabulary in the novels the students will be reading in their English classes. I am second year elementary ESL teacher and the only ESL teacher in my building. I service about 80 students. I have heard many of the teachers make comments about a student’s ability to speak and wonder why they are not doing well academically. They tend to equate a student’s social language with their academic language. I have made suggestions for teachers to use linguistic frames, but only a few have used them in their classrooms. I’ve been struggling to get the content area teachers to see that what they do in the classroom also effects how well our students do on the state language assessment. I know that all of our ELLs’ learning cannot be placed solely on me. What steps did you take to help your teachers understand their role in students’ language development?

Great article!

Valentina,

Great article. I really like how you clearly explained the strategies. These strategies can be so helpful for ALL students. Using these strategies can truly benefit students who struggle to learn and then communicate their learning. Your presentation and explanation is so clear! I will surely find it easy to share with content area teachers at my school! Thank you!