In the Heat of Learning, Good Questioning Is Key

In the heat of a game, coaches call time-outs to stop the action and provide feedback to players to enhance their future play.

These pauses afford opportunities for coaches to reinforce positive performance, activate their players’ prior knowledge/skills, and assist team members in customizing what they know to fit a current situation.

Time-outs also provide players an opportunity to stop, reflect, and identify gaps between what they have been doing and what they know how to do. With a chance to reflect, they can make real-time adjustments as they move forward.

Classroom teachers also resort to time-outs when they sense their students are off-course and there’s a need to redirect or reteach. When time-outs are unplanned they can interrupt the flow of the lesson, and most teachers use them sparingly – breaking the learning rhythm only when feedback suggests there’s a need for immediate corrective action.

Time-Outs: What Mary Rowe Discovered

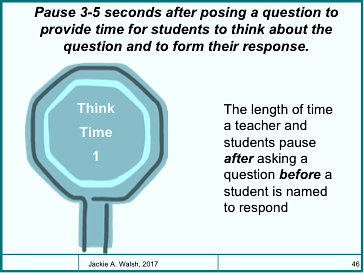

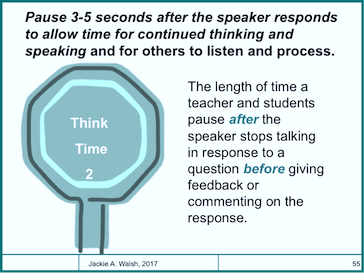

Within the classroom setting, there is also the potential for briefer, routine time-outs that “go with the flow” and support continual, reciprocal feedback between teacher and students. These pauses, referred to as Think Time 1 and Think Time 2 (aka, wait time 1 and wait time 2), provide students and teachers alike the chance to form, interpret, and use feedback to advance learning.

Rowe found that, after asking a question, teachers waited on average one second for a student to begin an answer – and less than a second after the student stopped speaking before reacting to what the student said (Rowe, 1996).

After some experimentation, Rowe discovered that an extended pause following the asking of a question (Wait Time 1), and another extended pause after a responding student stopped talking (Wait Time 2), resulted in multiple learning benefits. These included increases in the length of student responses, the number of questions asked by students, student confidence, speculative thinking, and a decrease in “I don’t know” answers (Rowe, 1996).

Further research also revealed benefits to teachers, including: a decrease in the number of questions asked, an increase in the cognitive level of questions, higher expectations for traditionally lower achieving students, and an increase in probing and other follow-up moves to get behind student thinking (Rowe, 1986; Tobin, 1986).

These pauses can be powerful and productive, but they only work when all parties know what to do during the silences and are committed to these actions.

Using Think Time Pauses for

Real-Time Formative Feedback

As I’ve partnered with teachers to improve classroom questioning practices, we’ve discovered that intentional use of these two pauses can also enhance the quality of real-time formative feedback to both teacher and students. Here’s how to set the stage.

1. Begin with shared mindsets

First, teachers and students alike must believe the purpose of questions is to surface where students currently are in their understanding – not just to solicit “the teacher’s answer.” This shift from fishing for the “right answer” to a learning orientation can represent a sea change in thinking for many students and teachers. However, without this shared belief, teachers are likely to provide an evaluative (i.e., “right” or “wrong”) reaction to a student statement rather than a formative one designed to move learning forward.

A second mindset, and a companion to the first, is viewing responding as a process that involves multiple exchanges between teacher and students en route to a more complete and correct result – not as a “one and done” transaction involving a single teacher question and a short student answer.

This second shift paves the way for both teachers and students to use Think Time 2 to reflect on an initial response and form feedback to the speaker.

2. Provide time for students to form responses (not ‘answers’)

In introducing these two mindsets to students, we’ve found it helpful to substitute the phrase “respond to” for “answer”—and to explain why the distinction. Traditionally, teachers call on volunteers with raised hands to answer questions. The “usual suspects” try to raise their hands first to receive positive feedback. Their answers are usually brief (on average 3-5 words) and final.

In contrast, responses resulting from deeper thinking are more elaborated and complete, providing teachers with richer and more accurate feedback regarding where students are in their learning and enabling more substantive and supportive feedback from teacher to students.

Deeper thinking requires time, the time afforded by the first pause.

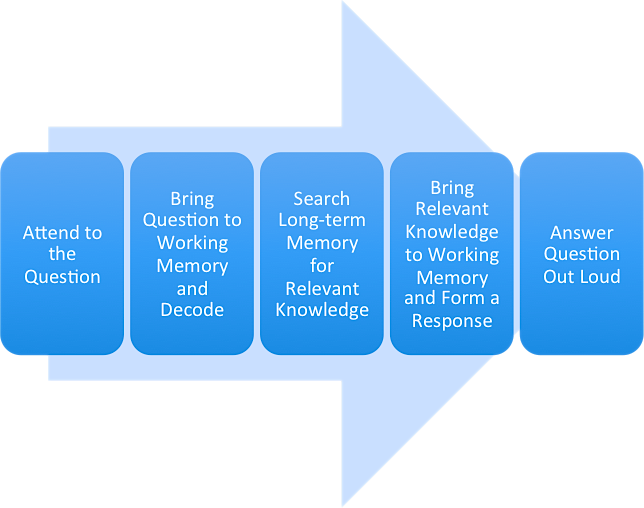

The illustration above depicts the process for thinking in response to a question. This is adapted from the work of cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham, who calls this “the simplest ever model for how thinking works.”

Consider presenting this visual to students as a metacognitive lens through which to understand the “why” of Think Time 1. Most students quickly conclude that thinking takes time, and appreciate that individuals require different amounts of time to move through this process. The goal is to promote a new norm for classroom interaction: “We all need time to think prior to responding to a question.”

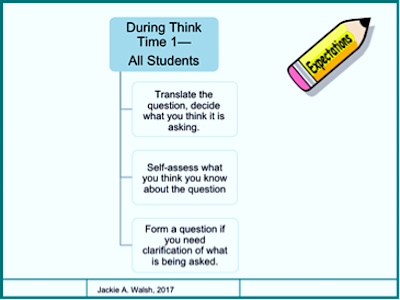

It is not enough for students to understand the how and why of the first pause. To use Think Time 1 to generate rich feedback to their teachers, they need to learn exactly what to do during this silence.

These questions help students surface what they think they know. It may be correct or incorrect – sound prior knowledge or a misconception. But a student’s response provides accurate, real-time feedback that informs the teacher in preparing needed support.

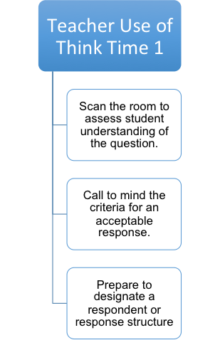

This first 3-5 second pause also provides teachers with time to be thoughtful as they seek to secure feedback from students that is valid and will improve the quality of teacher feedback to students.

If looks of confusion predominate following a 3-second pause, the teacher might ask one student to restate the question in her own words (clarifying the question if required). The next step is to call to mind the criteria for an acceptable response in preparation for listening to the respondent.

Finally, the teacher decides who to call on or or whether a paired response prior to an individual one seems appropriate. These metacognitive moves enhance the value of student responses as feedback to the teacher.

3. Self-assessment, correction and elaboration

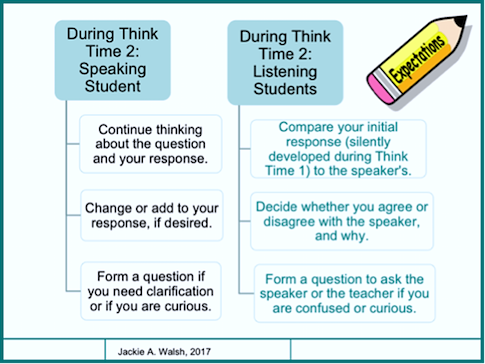

Think Time 2, the 3-5 second pause following a student comment, has formative value for both speaking and listening. This pause provides students who are listening with an opportunity to make meaning of a speaker’s comment and compare it to their own responses, continuing the process of self-assessment begun during Think Time 1.

Listeners are also expected to formulate a comment or a question, preparing to offer peer feedback to the speaker if called upon to do so. Meanwhile, the speaker can continue to think about the question, reflect on the proffered response, and elaborate or self-correct. This figure illustrates explicit expectations to convey to students as you assist them in developing the metacognitive thinking associated with productive use of this pause.

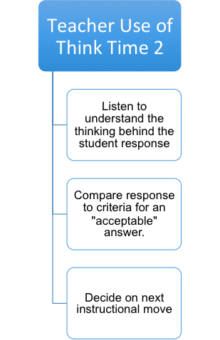

This second time-out in the flow of an interaction provides teachers an opportunity to enhance the quality of feedback to students. Consider three strategic metacognitive moves at this juncture:

► While listening, we need to be comparing a student’s response to criteria for an acceptable response to identify possible gaps in understanding. These two moves enable teachers to decide upon the most appropriate feedback to the student.

► Whether a student offers a correct or incorrect response, the most productive feedback is usually another teacher question, one designed to get behind student thinking and invite elaboration on the first response.

Ron Ritchhart, a cognitive scientist at Harvard, found that the most effective follow-up question is “What makes you say that?” When posed following an incorrect response, this query can help pinpoint a specific area of misunderstanding or confusion, which allows the teacher to customize additional feedback. In the case of a correct response, this follow-up question invites elaboration, justification, and deeper thinking.

4. Real-time adjustments

Quality feedback is reciprocal. When teachers use student responses to questions as feedback from their students, they can, in turn, provide effective feedback to these learners. Interpretation and use of feedback require time if adjustments in teaching and learning are to ensue. Think times provide a break in the action that enable these outcomes if and when teachers adopt associated mindsets and routines and explicitly instruct their students in the what, why, and how of these time-outs.

References

Ritchhart, R., Church, M., & Morrison, K. (2011). Making thinking visible: How to promote engagement, understanding, and independence for all learners. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Rowe, M. B. (1996). Science, Silence, and Sanctions, Science and Children, 3, 35-37.

Rowe, M. B. (1986). Wait Time: Slowing Down May Be A Way of Speeding Up! Journal of Teacher Education, 37(1), 43–50.

Tobin, K. (1986). Effects of Teacher Wait Time on Discourse Characteristics in Mathematics and Language Arts Classes. American Educational Research Journal, 23, 191–200.

Walsh, J.A., & Sattes, B. (2017). Quality questioning: Research-based strategies to engage every learner (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks: CA: Corwin.

Author and educator Dr. Jackie A. Walsh is a leading authority on using effective questioning to advance learning. She is the co-author, with Beth Sattes, of Quality Questioning: Research-Based Practice to Engage Every Learner (Corwin, 2nd Edition, 2017) and Questioning for Classroom Discussion (ASCD, 2015).

Dr. Walsh is also a lead consultant for the Alabama Best Practices Center, which affords her the opportunity to work in classrooms and with networks of school teams, district teams, instructional partners, and superintendents.