Replace What Doesn’t Work with What Does

A MiddleWeb Blog

In general, we don’t spend a great deal of time with our students. So it’s important to make the most of the time we do spend with them. For English learners in the middle grades, this is even more critical.

In general, we don’t spend a great deal of time with our students. So it’s important to make the most of the time we do spend with them. For English learners in the middle grades, this is even more critical.

Students who are in grades 4-8 and adding English language learning while also learning new content need efficient and effective instructional opportunities that will advance their language and academic performance.

There’s no time to waste. The sense of urgency on our part and theirs should be great.

How do we do this? We can begin by taking a look at our routines and practices and considering the effect they have on language and learning. Consider these ideas:

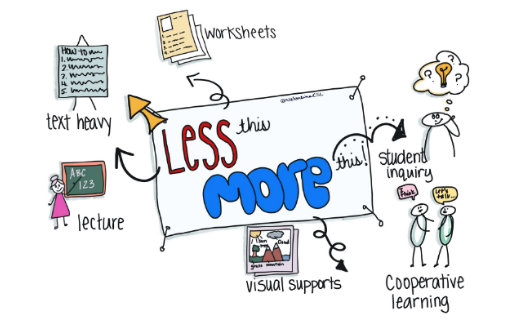

Fewer worksheets. More cooperative learning.

Typical classroom instruction might include a teacher-led lecture followed by an assignment for students to complete on paper individually. Imagine if you were an English learner or any student and you spent most of your day listening to each teacher talk. Then you completed a related assignment. Then you did the same thing in the next class. And the next.

How effective would this be? Would you learn to use academic language in speaking and writing? Would you progress academically and linguistically? Would your progress be rapid?

In contrast to offering assignments for students to complete individually, we can offer cooperative learning opportunities. According to Kagan, cooperative learning refers to instruction that is held in small heterogeneous groups of students who work together to achieve a common goal.

It supports English learners because the grouping allows for a constant stream of communication with native English speaking peers who serve as models. English learners are able to practice listening and speaking in a small setting, providing more opportunities for interaction.

Less lecture. More student inquiry.

One way to break up the teacher talk and make space for student inquiry and empower students to take ownership of their own learning is to structure some lessons using the Talk, Read, Talk, Write framework by Nancy Motley.

You can learn more about it from her book, Talk, Read, Talk, Write and also from this blog post by Tan Huynh. This will move instruction from being teacher centered to student driven. Here’s a sample classroom scenario for a Talk, Read, Talk, Write lesson in social studies:

Talk 1: Should Supreme Court members be elected by the people instead of appointed by the President?

Teacher: Take a minute to think about this question in your mind. When you can complete this sentence, stand up: “In my opinion, Supreme Court members should be…because…”

Read: Now students are given a text to read. This text is directly related to the topic that was discussed in Talk 1. For this example, students read about how Supreme Court members are elected. They read about the process. The teacher gave them a purpose for reading.

Teacher: While you read, make annotations. Highlight information that is new to you. Place a question mark by information that you don’t understand. And put a star by information that you already knew.

Talk 2: After students read the text, they reconvene in small groups of 2-4 to discuss. The teacher can give students specific questions to answer or open this up for a more student-created conversation. The important part of this Talk is that it bridges the reading and the writing. It serves as a scaffold.

Teacher: It’s time to check-in with your group to talk about the process of becoming a Supreme Court member. Take your text and notes to help you use textual evidence. As you discuss your annotations, remember that each member should share either a comment or a question. Okay, you will have seven minutes to discuss.

Write: Now that students have had time to listen, read, and speak about the topic, they will write about it. In this case, the teacher asks students to write in their journal.

Teacher: Take out your journal and write about the process of becoming a Supreme Court member. Share the process and how you would change it if you could.

Less text heavy. More visual support.

No matter what we teach, there are students who will benefit from the support of visuals. Let’s just think about our content. If a student lacks the academic vocabulary to comprehend the content that we teach, visuals can support their understanding. It doesn’t even matter if they are an English learner.

Many of our English-only students need support with academic language as well. We can take a text-heavy assignment, reading, anchor chart, etc. and use visuals to make the assignment more accessible to all students.

Visuals come in various forms. Here are a few ways to enhance instruction with visuals:

- Labeling a graphic or picture with students (Picture Word Inductive Model)

- Adding visuals to word walls

- Using videos or interactive media

As we reflect on our own teaching and learning, we realize there’s so much more. What else do you think we need less of and more of in classrooms?

Hi,

I would love to see your ideas or read your blogs through email please. Not a huge twitter user. Thanks!

Hi, Stephanie, You can read Valentina’s MiddleWeb posts at https://www.middleweb.com/category/unstoppable-ell-teacher/ any time. Her own website is here: https://elementaryenglishlanguagelearners.weebly.com/blog . Susan at MiddleWeb

“Talk Read Talk” is a great strategy to reinforce subject-matter. This pedagogical learning is often utilized with “chunking”. Chunking occurs when there is a segment of information given, followed by a group discussion and then reconvening to summarize what the students have learned.

Thank you for posting these wonderful and effective strategies to be used in the instruction or facilitation in the learning of English proficiency. I would love to see all of these strategies implemented via the native language. It is a well-known fact that language mediates access to content. Language barriers are real, therefore there is a need to provide appropriate academic instruction through the home language with effective strategies so that these students have a real opportunity to reach grade-level achievement while learning English proficiency (3-5 or 7 years). As a nonnative speaker of English in college, I experienced directly how impossible it is to learn meaningful concepts through a language one does not yet understand proficiently. Colleges and universities understand this issue quite well…