The Learning Power of Cliffhangers & Link-Ups

A MiddleWeb Blog

I started saying it because it amused me:

I started saying it because it amused me:

Stay tuned for tomorrow’s episode in which we will look at the part of the Declaration of Independence that Thomas Jefferson cut out because it was so controversial…

Or…

Now that the United States has acquired the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Guam, tomorrow we will look at the key piece of the puzzle that will connect America’s new empire…

Then I began to notice students talking to each other after the bell rang about what we had done in class and what might be next. So I began to intentionally end class with a “cliffhanger,” leading to an obvious entry point for the following lessons.

A lesson on corruption in Congress using the famous Bosses of the Senate political cartoon can end with the dramatic, “would the government do anything to regulate the power of monopolies? Stay tuned for tomorrow’s lesson…” which segues nicely into a look at the Sherman Antitrust Act.

Why not give lessons titles?

“The Tragedy of the Triangle Fire and the Need for Government Intervention” or “Toussaint Louverture, Napoleon Bonaparte and Thomas Jefferson, or how a slave revolt in Haiti doubled the size of the United States.” Such a title might perk their interest a bit more than one on the Louisiana Purchase. Gimmicky? Perhaps, but when we are competing with so many things for students’ attention, why not give these link-up strategies a try?

Cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham has noted that students are likely to pay increased attention to stories. But it’s not just about telling the good stories in American history. It’s also about making connections among the multitude of facts with which students are presented. We can make choices about which stories, which facts, and which historical figures to introduce. (Teachers in other content areas will be quick to see the possibilities across their lesson plans. But I’ll stick to history here.)

Threads through US History

For example, in my unit on Industrialization in the late 19th century, I might have chosen the Baltimore Railroad strike of 1877 or the Homestead Strike of 1892 as case studies of labor strife. Instead, I choose the Pullman strike of 1894.

I choose Pullman not only because it occurs in Chicago, which is where I teach, but also because Pullman cars will play a role in future stories I choose to tell. Booker T. Washington, for example, was able to avoid a group of angry whites who boarded a train and searched in all the public cars for him – because he had booked a private Pullman car.

Later, when we get to the Great Migration, students learn about the role that Pullman porters played in distributing copies of the Chicago Defender in the South, helping African Americans learn of opportunities in Chicago. And finally, A. Philip Randolph, the leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, played a pivotal role in organizing Pullman porters and would challenge President Roosevelt during World War II, resulting in Executive Order 8802 (1941) which banned discrimination in the defense industries.

Making the connections

Think about what you teach, and how you can connect facts, people and events from one unit to past and future units of study. Students should see the things they learn about as something more than an item in one unit that is learned and then forgotten.

There are good cognitive reasons to making such connections. Students are better able to learn new information when it is connected to previous knowledge. Daniel Willingham makes this point very clear in an intriguing article about background knowledge and reading comprehension.

This year, on the first review sheet for the first unit test, I included the following point:

One of the things we can do to help our students is to make these connections visible. We should have a reason why we are teaching about Jane Addams and Hull House on Tuesday and the women’s suffrage movement on Wednesday. Making those reasons clear to students will help them with the task I highlighted on my review sheet. We can do this when we ask students for a brief review of the previous day’s lesson as a segue to today’s lesson.

Students uncover cause and effect

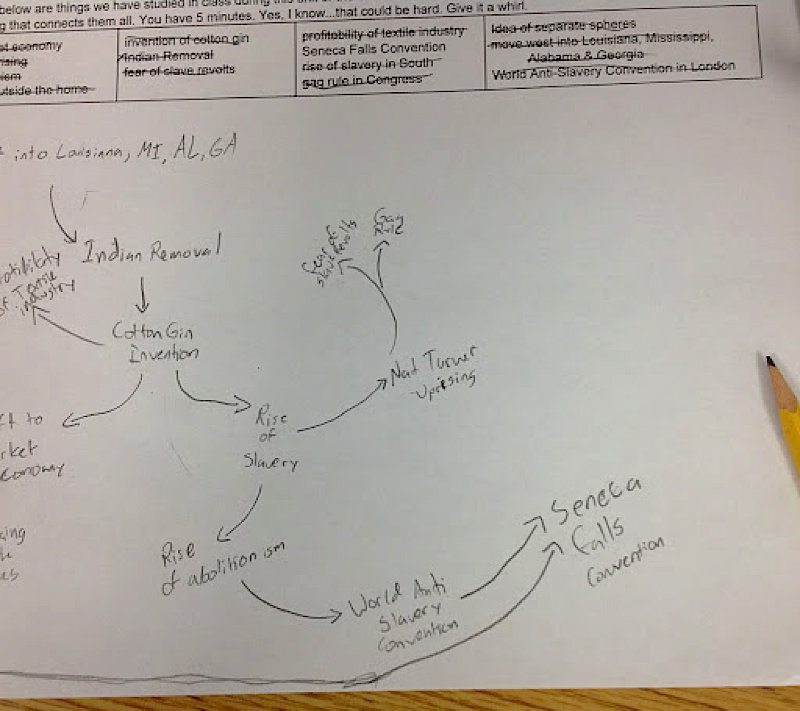

A few years ago, I created a lesson for my 7th graders to encourage them to find the connections among an entire unit’s lessons. Based on a post I wrote on my U.S. history blog, I created a lesson in which I gave students sheets of paper with items involving the antebellum era while other students got cards with arrows on them. They were instructed to “put them into some kind of order that shows cause and effect among and between items.” There were few instructions other than this; I was curious what students would do.

I didn’t know what to expect but was thrilled with the results. Students were up out of their seats, talking to each other about what the changing role of women in the market economy had to do with the abolition movement and what that had to do with invention of the cotton gin.

Below, one student’s notes from the lesson.

Linking one unit to the next

This can also be done with entire units. Look at the two examples below. Consider how you might share this with students as a review activity at the end of one unit and before another.

In our unit on Colonial America we saw that the colonies grew and became increasingly economically & politically self-sufficient. This led to our unit on the American Revolution in which the colonies wanted no taxation without representation, and so broke away from Great Britain. They were convinced that a republican form of government was best and so when the Articles of Confederation didn’t work out, they wrote a new Constitution.

Or this one:

It wasn’t just the U.S. that was expanding and industrializing in the 19th century. Europe was too. And so Americans became interested in maybe expanding our reach into colonies, leading to Becoming a World Power by taking over the Philippines and Puerto Rico, among other places. This expansion of American power and industry would lead us into World War I, but Americans were disillusioned by the experience and so retreated into the isolationism of the 1920s which wouldn’t change until events of the 1930s led the world into World War II.

Try experimenting by having students write their own summaries, alone or in groups. Or perhaps, similar to the arrow/card activity above, give students phrases from paragraphs like the ones above and have them put a sequence in order. Or try the activity where you start with a phrase or a sentence and then have pairs of students try to write the next sentence.

Understanding cause and effect

A deluge of facts in history class won’t build understanding. History teachers know this. Hooks, cliffhangers, and connectors can help.

Linking one event or person to later developments opens students up to seeing how pieces of the massive puzzle of the past fit together, not always neatly, and how the issues we face today developed over centuries.

Making connections in history is such an important, but difficult skill. When teaching about ancient civilizations, I encourage my students to find the patterns between them. By the middle of the year, it becomes a game for them!

Lauren, this article gives so much food for thought. I love the idea of selecting key events that will connect to another unit, such as the Pullman Strike and A. Philip Randolph. The “cause and effect map” is such a great collaborative activity and takes the concept map (www.middleweb.com/29037/how-going-deeper-looks-in-a-concept-map/) a few steps further. Thanks for all these ideas.

Thanks so much, Sarah!