Close Reading in Science Deepens Understanding

The work of scientists involves so much more than investigations and experimentation.

The work of scientists involves so much more than investigations and experimentation.

Science starts with a question about the natural and man-made world. Scientists wonder and inquire, talk, write, and read.

And their process is iterative. After a question is asked, these components can happen in any order, but each component is almost always present when good science is taking place.

Classroom science studies should emulate what is happening in the real world of science. This means that our students are not only questioning, investigating, talking and writing – they are reading about science as well.

Science-related reading is not only enjoyable and informative but it is an expected element of the three-dimensional learning described in the New Generation Science Standards. Let’s take a closer look.

How do science teachers fold reading into their instruction?

I recently had the wonderful opportunity to work with teachers who were more than a little interested in how they could strengthen their science instruction and also help improve the reading skills of their students. This topic has long intrigued me.

Close reading in science means getting our students to focus on the text with intentionality. If we are reading in science, we are reading for information, often trying to locate additional evidence to support or verify the evidence we found in an investigation.

Providing periodic opportunities for our students do a close reading in science will help them become better learners about science and also foster students who can read independently and extract the meaning when dealing with complex texts in any content area or life situation.

Multiple readings should be the norm

Close reading in science means reading the text multiple times. Helping students see the importance of multiple reads is critical. They need to know that good readers almost always do multiple reading of informational texts, especially when they are seeking an answer to a particular question.

Often, it is only upon reading a text the third time that the reader is ready to do a deep dive and begin evaluating – determining if this particular text supports or extends their previous work with the topic. Does it provide additional evidence? Does it verify or does it raise more questions to investigate?

Focused partner reading

Another strategy for developing literacy skills in science – and making the text more accessible to all students as we expand student understanding of a science concept – is to engage them in a focused partner reading.

There are many variations that can be determined by the teacher. For example, for a struggling reader or EL student, the procedure might include a good reader beginning the process and the reader in need of extra support reading in unison (shadowing). The two would then discuss the selection they’ve read together and move on to the next one.

Another variation might be Partner 1 reading aloud a few sentences. Partner 2 would then summarize, ask a question about the content, the text structure, or the academic vocabulary that is necessary for understanding the concept. Roles can be switched. Teachers can develop a variation of a focused partner read that works best for their students.

Helpful tools

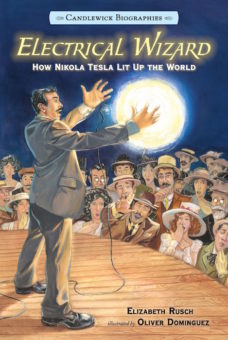

One example I have of a close reading exercise is one I developed with my literacy colleague using the trade book “Electrical Wizard: How Nikola Tesla Lit the World.” The lesson is a scripted example of using close reading and text-dependent questions to enhance student understanding of how electricity works and the transfer of energy .

The NGSS Connection

Reading in science is an expectation of three dimensional science instruction that can be found in the Framework of K-12 Science Education as well as the Next Generation Science Standards. When students are reading in science, they are engaging in the science and engineering practice of obtaining, evaluating and communicating information.

The Middle School (Gr. 6-8) NGSS discussion includes this language:

Critically read scientific texts adapted for classroom use to determine the central ideas and/or obtain scientific and/or technical information to describe patterns in and/or evidence about the natural and designed world(s). [Source]

Some additional resources about reading in science:

Text Complexity in Science – Resources for Teachers (Wisconsin DPI)

Strategies for Teaching Science Content Reading (ERIC)

Richard Feyman: The Making of a Scientist – Grade 6 Example (Achieve the Core)

Science and Literacy (Boston Public Schools)