Using Mood and Imagery to Engage Kids with Text

By Trevor A. Bryan

By Trevor A. Bryan

You have about 10 minutes of class time. Is it possible to help students…

- Find Key Details

- Synthesize Key Details

- Make Inferences

- Use Evidence to Support Thinking

- Identify Possible Themes

- Make Meaningful Strong-link Connections

- Use Symbolism

- Make Reasonable Predictions

- Explore Story Structure

- Explore Writers’ Craft?

Perhaps surprisingly, the answer is yes. Even if your students aren’t the most proficient decoders, you can help them engage with these skills and strategies through quick and easy conversations. How? Well, the answer is quite simple: by using visual texts such as illustrations, paintings, and photographs.

My book, The Art of Comprehension: Exploring Visual Texts to Foster Comprehension, Conversation, and Confidence, explains how. The approach is designed to help all students connect with the skills they need for academic success and to become active members of the classroom community.

The approach builds on a foundation of three simple questions:

What’s the mood?

How do you know the mood?

What’s causing (or could cause) the mood?

These questions may sound simplistic, but they are extremely effective in helping students to start thinking about the texts before them. Let me briefly explain why and then we’ll look at an example.

What’s the Mood?

Whether they are fiction or nonfiction, stories are told through mood. This is because stories are usually built, at least metaphorically, around our human experience. And our human experience is driven by our reactions to the events, people and dreams in our everyday lives.

Reactions reveal and influence our moods. Therefore, identifying, tracking and exploring moods in stories and other creative forms is an easy way to enter into them.

How Do You Know the Mood?

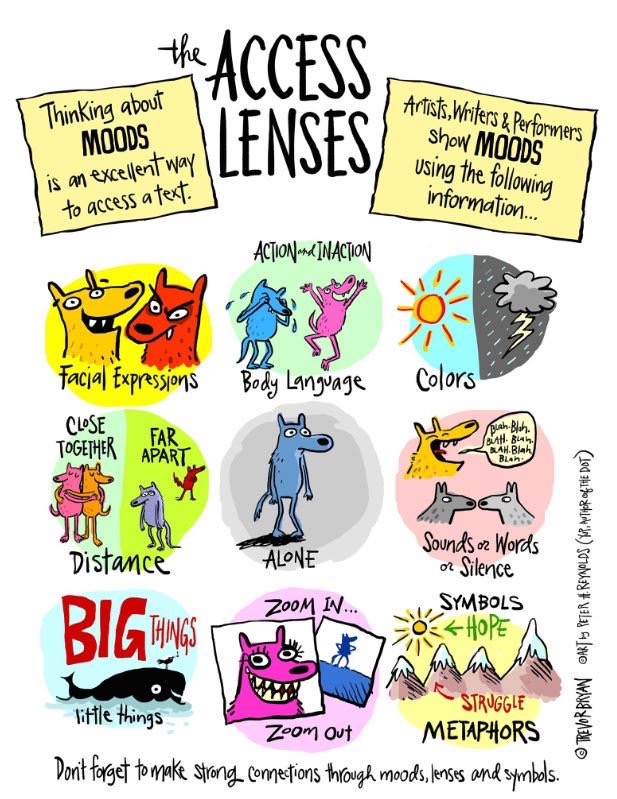

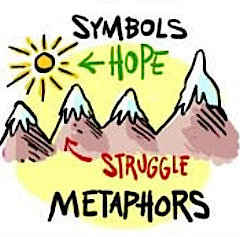

This question is asking viewers to identify the key details they notice, synthesize them, and use them to support their thinking. To help students notice key details, I created a tool illustrated by Peter H. Reynolds, titled the Access Lenses.

Humans can only show moods in so many ways. Whether we are looking at pictures, reading books or watching movies or plays, these lenses occur over and over in the work, showing the audience the characters’ reactions as events unfold and reveal their moods.

The Access Lenses, illustrated by Peter H. Reynolds. Click to enlarge or download.

What’s Causing (or Could Cause) the Mood?

Once the audience knows the mood, the next thing they need to know to understand the story is what is causing the mood. Sometimes this question is answered quickly and clearly. Sometimes audiences have to wait for this question to be answered.

In written stories or plays and movies, if this question isn’t answered right away, the audience’s job is to look for the answer. In single images, such as paintings and photographs, the viewer won’t always know the exact cause of the mood being portrayed. Sometimes there are clues, and sometimes it’s up to the viewer to bring their own life experiences and background knowledge to the piece.

When viewers do have to call on their experiences and background knowledge to decipher the mood of a piece, this is an easy way for them to practice making strong-link connections.

Let’s look at a quick example to see how this all works using the opening illustration from Peter H. Reynolds’ book, The Dot.

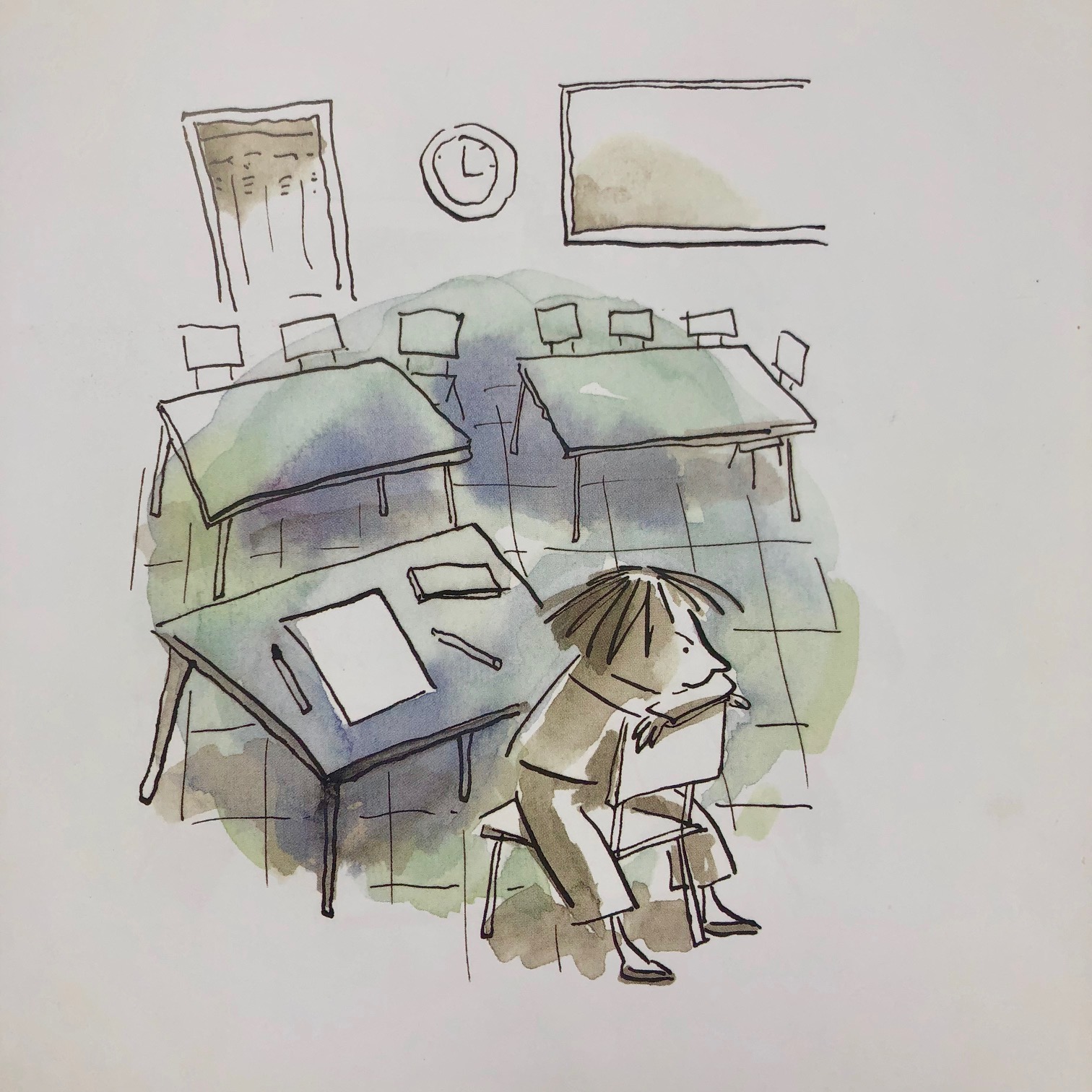

Illustration from The Dot, by Peter H. Reynolds

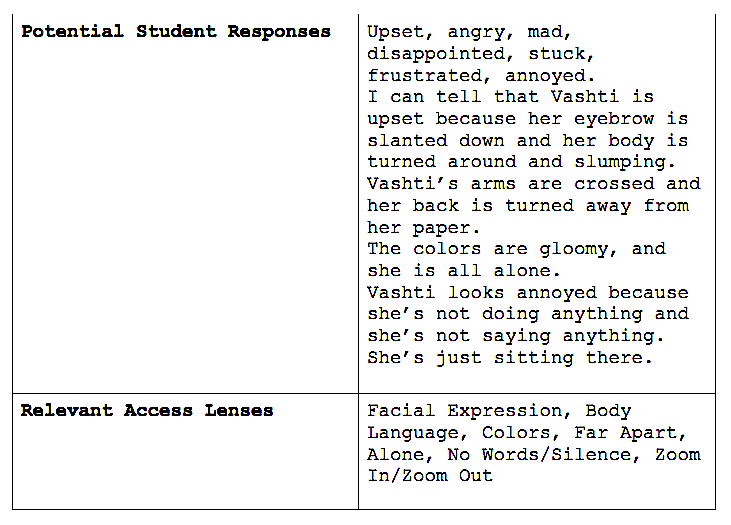

So what’s the mood? Take a moment to look at the Access Lenses and see if each lens can help you notice key details that help you infer the mood of the main character, Vashti, who is depicted in the picture.

Did you make an inference? Do you have a mood in mind? What words can you use to describe her mood? Sad? Upset? Frustrated? Isolated?

When you ask your students to come up with a list of words that could describe Vashti’s mood, you are helping all students to join the conversation and explore vocabulary. Striving students may use simpler words, and soaring students might use more sophisticated vocabulary. Once students have a mood in mind, if it’s based on the text evidence, they are right in the heart of the story.

Student responses: How do you know the mood?

Below are some examples of potential student responses that use textual evidence to support their thinking:

Identifying Possible Themes

The above illustration shows a girl sitting in an art room by herself. That’s what it shows, but that’s not what the picture is about; that’s not a theme of the picture. What the picture is about is feeling stuck or frustrated or upset. That’s why Peter Reynolds created this picture.

Once students identify a mood of a picture, they are really identifying a possible theme or big idea of a story. If students know the actual cause of the mood, then they are really in the thick of theme. In the case of Vashti, she feels upset or stuck or frustrated because she believes that she can’t draw. If students identify the reasons for a mood and string them together, they have a theme or big idea. In The Dot, the theme might be stated this way: When we believe that we aren’t good at something, it can make us feel frustrated, upset, stuck or isolated.

Making Strong-Link Connections

Moods also present good opportunities for students to make meaningful connections. When students identify Vashti as feeling upset and then identify with the mood of feeling upset by recalling a time in their life when they felt that way, or when they have encountered another character from another story who felt that way, they are demonstrating that they comprehend the story and are developing and exploring empathy.

Furthermore, when they make a strong-link “text-to-self” connection about times they have felt like Vashti, they have a potential idea for telling some of their own story.

Symbolism

To think about this concept another way, consider how your students feel about gym class. For some of them, gym may fill them with excitement. For others, gym might fill them with dread. Same event. Different reactions. Different moods. Different symbolism.

Making Reasonable Predictions

During the course of a story, mood may change, perhaps more than once. Characters have some problem, difficulty or struggle that they have to work through. In the majority of stories written for young people, main characters wind up successful and the story ends up with them being in some happy, positive mood.

Once students have identified a mood (whether positive or negative) based on the textual evidence, an easy way for them to think about making a prediction is by asking themselves, “What would cause the character’s mood to change?”

What would change Vashti’s mood? Knowing that she feels upset because she can’t draw, students might predict that someone will come over to help her. Maybe she gets an idea. Perhaps she’s even told that she never has to draw again in her life. Based on the textual evidence, all of these predictions make sense. Once a prediction is made, a reader’s job is to read on to see if their prediction is correct.

Exploring Story Structure

Understanding that stories have changes in moods is also a way for students to think about story structures. Knowing that when a character is wrapped up in some negative or positive mood their mood is bound to change helps readers become more aware of how stories are put together. This awareness of how professional story-sharers structure their stories makes it more likely that students will utilize these structures in their own writing.

Exploring Writers’ Craft

The Access Lenses can also help students think about elaboration, adding key details and showing, not telling, in their writing. When students use the Access Lenses to pull details out of visual texts, it can help make the kinds of details they need to put into their own writing more apparent – more concrete. For instance, if one of your students was writing about a character who felt frustrated, they may be able to take a page from Peter H. Reynolds and write something like…

I was so mad! I crossed my arms, turned my back and didn’t say a word to anyone.

So Can All of This Work Really Be Done in About Ten Minutes?

Yes! Once you and your students get used to identifying moods using the tools I share in The Art of Comprehension, you will be well on your way to having rich, meaningful discussion about the texts you engage with in very little time.

The Art of Comprehension is an easy, student friendly approach that helps all learners become active members of the learning community. It has helped me to help many of my strivers find and share their voice, and it has helped me to help my more confident students soar. I am sure these ideas can help your students too. Let’s help every student to explore, find and share their voice. I hope you join me on this mission.

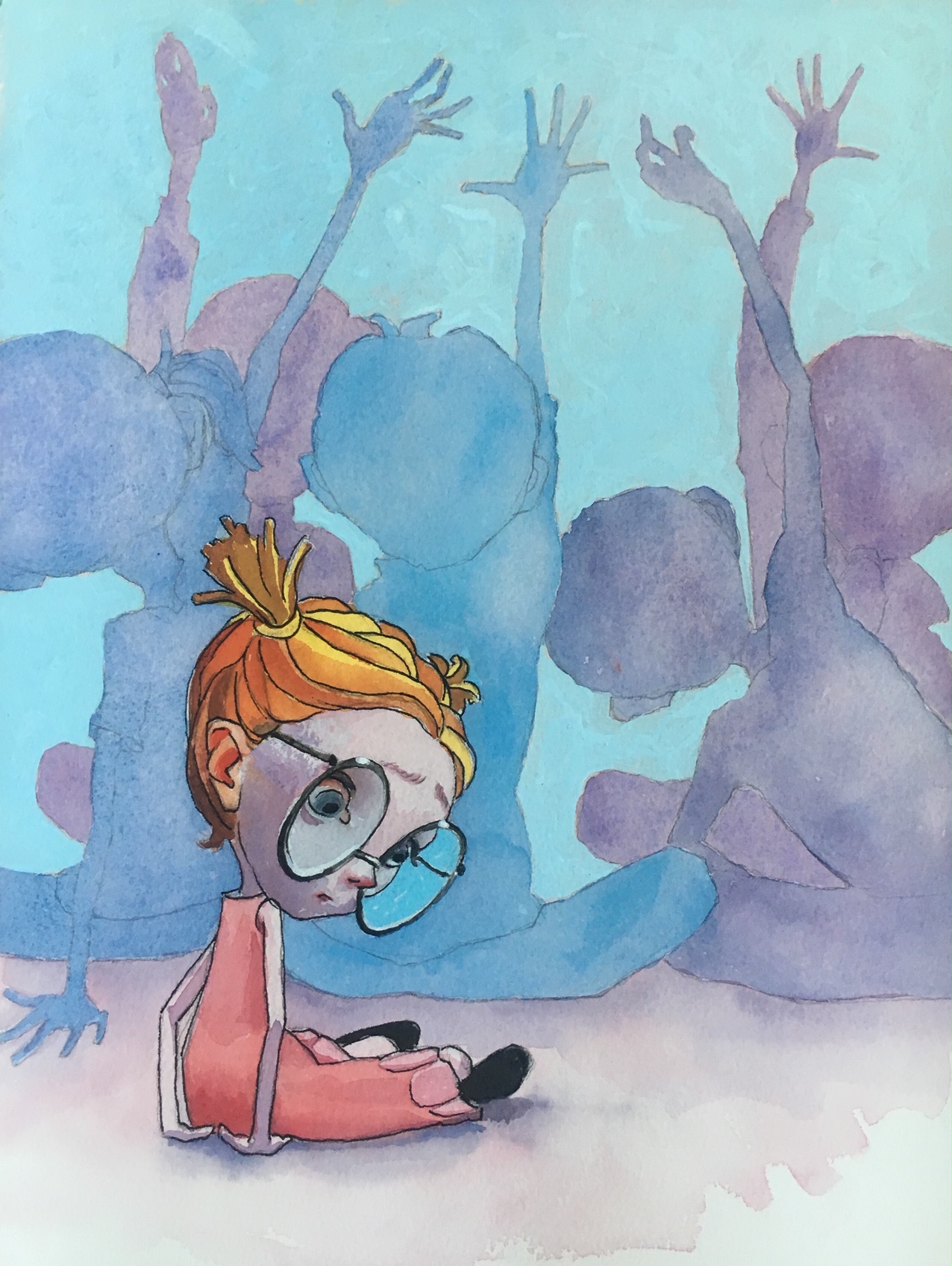

ANALYZE THE MOOD – Trip to the Museum, by Kyle Stevenson

This is so powerful.