Changemaker Questions Spark Student Learning

A MiddleWeb Blog

When I walked into a one-hour session at the most recent National Council for the Social Studies annual conference – a mega-gathering with ideas and fellow teachers spilling from every corner, not to mention a celebrity sighting of Constitution USA guru Peter Sagal – I didn’t expect to walk out ready to transform an entire unit in my eighth-grade history class.

When I walked into a one-hour session at the most recent National Council for the Social Studies annual conference – a mega-gathering with ideas and fellow teachers spilling from every corner, not to mention a celebrity sighting of Constitution USA guru Peter Sagal – I didn’t expect to walk out ready to transform an entire unit in my eighth-grade history class.

But my mind opened up as I sat in “Bending the Arc Through History and Literature,” listening to researcher Chaebong Nam give an overview of a civics framework, and hearing how Massachusetts teachers Elizabeth Olesen and Melissa Strelke used it in their classes.

I realized that the framework they were describing, developed through the Harvard Graduate School of Education, had the potential to deepen my teaching about historical, current and future activism.

Back in my classroom, in a reformers research project ripe for some updating, their ideas did just that.

The First Step: Understanding the 10 Questions

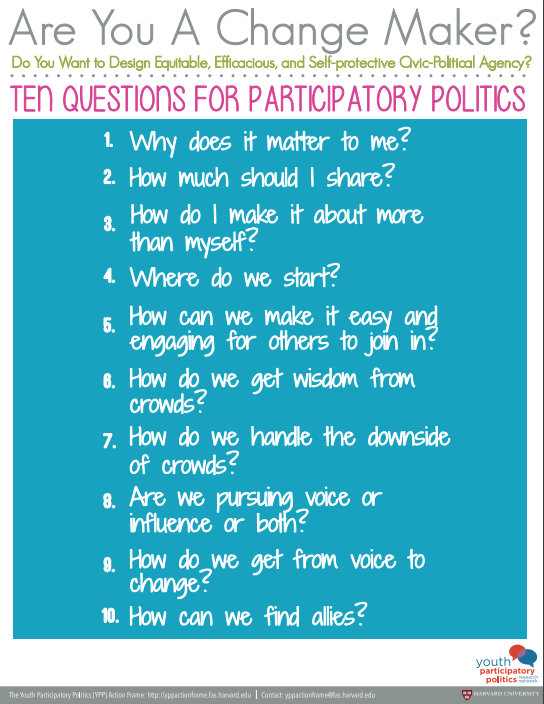

First I had to understand the framework, a series of “10 Questions for Participatory Politics,” also known as “10 Questions for Young Changemakers,” developed through the Democratic Knowledge Project at Harvard.

The list begins with the personal: Why does it matter to me? It then moves through practical questions, such as Where do we start? and ends by expanding our impact: How can we find allies?

As my eighth graders started a research unit on social reformers in U.S. history, I wanted them to hold these questions close.

How best to do this? I remembered a strategy I had tried with poetry when teaching English: “talking through” a poem line by line with a partner, even if students weren’t entirely sure what the words meant.

Similarly, they could “talk through” each one of the civics questions with a partner or small group.

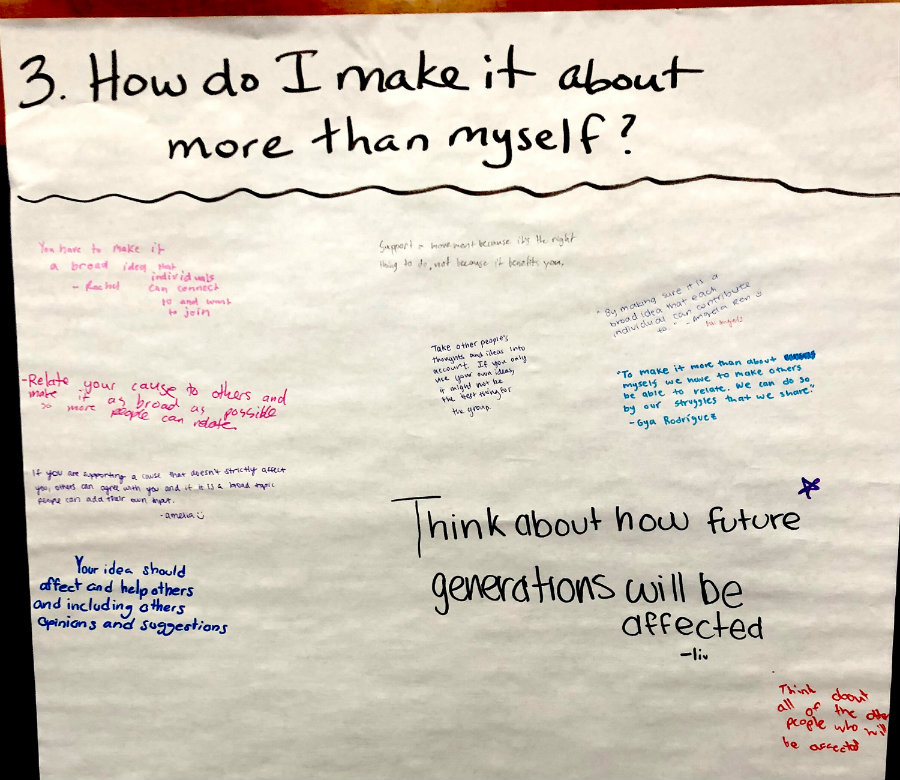

To stage this conversation, I wrote each question on a large Post-It on the wall. Each small group got 45 seconds per question, then rotated to the next. At the end, each student chose two favorite questions and wrote a comment or explanation on the Post-It for each.

By the end, we were physically surrounded by interpretations of the 10 Questions – a perfect place to begin doing research about change makers in history.

Bringing the Questions Into Historical Research

The beauty of these questions is that they can travel through time. How did change makers find allies in the past? How can we?

For the future, the 10 Questions for Participatory Politics can inspire students wanting to take action in their communities, who might be wondering, How do we get from voice to change?

For the present, the questions can shape discussions about current events. We can ask, perhaps, How do we get wisdom from crowds? in the wake of a protest or revolution.

And for history, the questions can ferret their way back in time to illuminate people’s motivations: examining, for example, how reformers in the past answered the question How do I make it about more than myself?

After my students had found and annotated sources about an activist in U.S. history for a reformers research project – with choices ranging from Frederick Douglass to Yuri Kochiyama – I asked them to think about which of the 10 Questions applied most to their person.

In their final paper, an extended body paragraph, they had to include a reference to one or more questions, explaining in at least one sentence how they related it to their reformer.

True Connections Through Time

Given that this “Changemaker” sentence was a quick addition to a paper I’ve been doing for a while, I was thrilled with how much it added depth to a biographical essay. Most often students placed the question right after the paper’s topic sentence, creating what I informally called a “follow-up topic sentence.”

For instance, Anya peered into political dynamo Phyllis Schlafly’s tactics by asking Why did it matter to her? and How did she make it easy and engaging for others to join in?

Phyllis Schlafly, a wife, mother, lawyer, and conservative activist, largely contributed to stopping the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) from passing and slowed down the feminist movement, largely by connecting herself to other issues and portraying herself as the ideal woman. By doing this she made it easy for others to join in her movement and helped others to understand why it mattered to them (Changemaker Questions #1 and #5).

Human rights activist Marian Wright Edelman, being the studious and overachieving person she is, has impacted millions of children nationwide by her passion to protect and improve their lives. Throughout her life, Marian has used “influence and voice” (Changemaker Question #8) and “found allies” (Changemaker Question #10) to help her in her work.

And Sarah, in a paper called “Horace Mann’s Education Expedition,” considered the spread of public schools in the 19th century:

Congressman and public school crusader Horace Mann vigorously ensured schooling among America’s youth in the nineteenth century, and he was determined to provide the children of the United States with a useful education so that they could have successful futures. Mann made his school system very simple for people to join by opening it for the public to utilize effectively (Changemaker Question #5).

One morning, as I peeled the huge Post-Its off the walls at the end of our unit, I found myself a little wistful. The sense of action behind the 10 Questions had inspired us for weeks.

One consolation? I know I’ll be returning to these tenets in years to come, ideally applying them not just to historical reformers, but to present and future student activism as well.

For more information and lesson plans about the Youth & Participatory Politics Action Frame Project, check out the Harvard project’s website, with many classroom ideas, as well as a lessons unit using the 10 Questions from Facing History and Ourselves.