How to Get Your Students to Ask More Questions

Why don’t students ask more questions in school? The short answer is that most students believe it’s their job to answer, not ask, questions.

What’s more, many think that asking questions might lead teachers to believe they’re not smart or suggest to their peers that they’re not cool. Others simply don’t know how or what to ask.

Even our learners who are willing to take risks may let a good question go. The teacher controlled, fast-paced rhythm of classrooms provides little opportunity for students to make a “bid” to interrupt the flow with a thoughtful (but potentially time-consuming) inquiry.

And yet, students learn more when they ask questions. Consider this response from a 14-year who was asked how she learned best: “When I am able to come up with questions of my own, it’s easier for me to understand and remember what we’re studying.”

This student has incredible insight into the relationship between questioning, thinking, and learning.

Five Ways to Encourage Your Students to Ask More Questions

What can teachers do to encourage and develop students as questioners? We can address both the will and the skill of our students to assume this active role in their learning. Here are five strategies to accomplish this.

1. Establish the expectation

Talk with students about the what and the why of questions—helping them to understand their role as questioners and the value of questioning to their learning. Communicate to students the expectation that they should use questions to support multiple facets of their learning. To support this, consider introducing the following mindframes for students.

- I ask myself questions to monitor my thinking and learning.

- I pose questions to clarify and deepen my understanding of academic content.

- I use questions to understand other perspectives and to engage in collaborative thinking and learning.

- I use questions to channel my curiosity and spark my creativity.

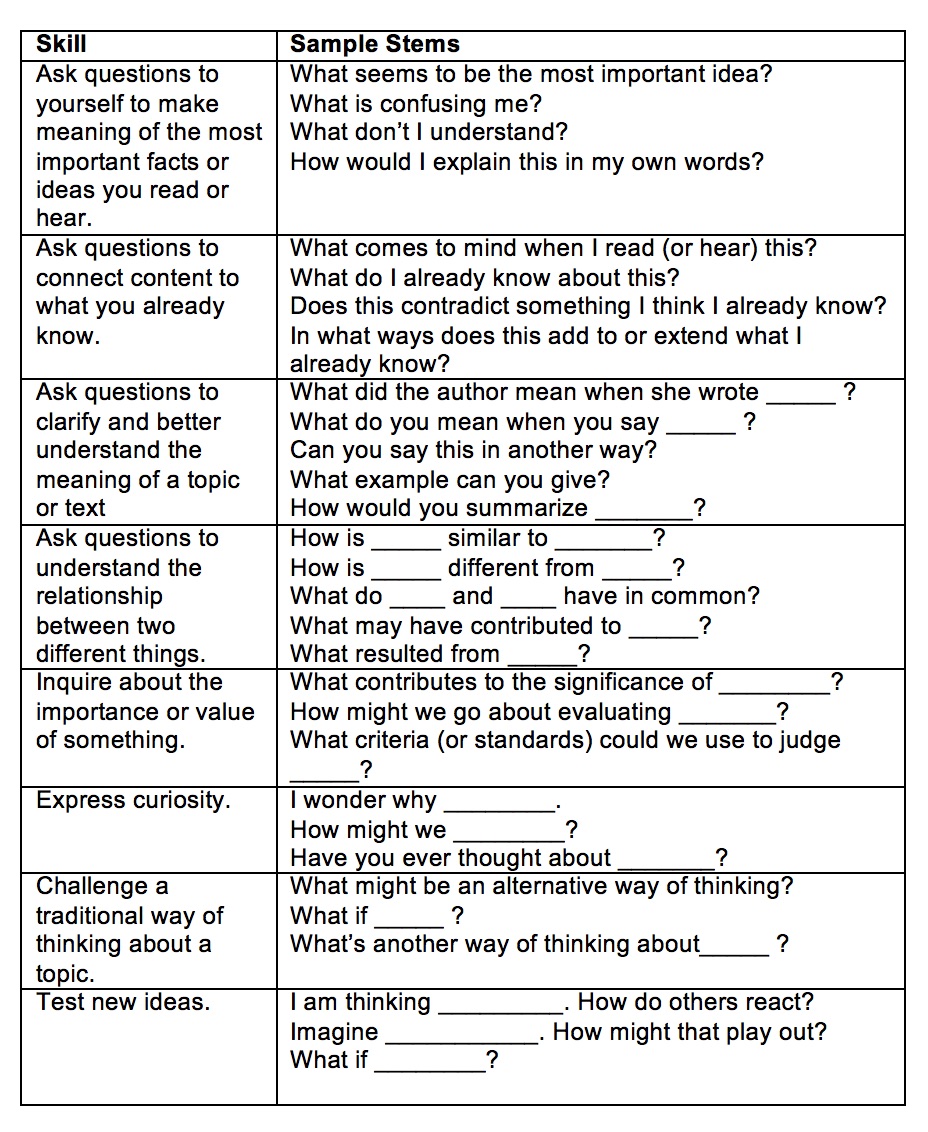

2. Develop skills for questioning

This involves identifying and communicating key skills and providing tools, for example, stems, to support each skill. Below are some sample skills and accompanying stems.

(Download)

3. Offer opportunities for practice

Teach your students questioning skills in a practice setting. This can be as simple as an assignment that calls for student creation of five questions about a homework or class reading. You might have them write down three for which they think they know the answers (closed questions) and two for which they do not (open-ended).

More structured practice might involve one of the Visible Learning Thinking Routines such as Think-Puzzle-Explore or See-Think-Wonder. When asking students to create questions, it’s important to give them a chance to use them – either posing them to classmates, using them for an investigation or research endeavor, or in some other authentic manner.

Providing feedback to students on the quality of their questions is also important if they are to improve their skills. The ultimate goal, of course, is for students to ask questions spontaneously as the need arises during instruction (for example, to clarify a point of confusion) or during a class discussion (when, for example, they are curious about an idea or about a classmate’s thinking).

4. Provide time and opportunity for questions

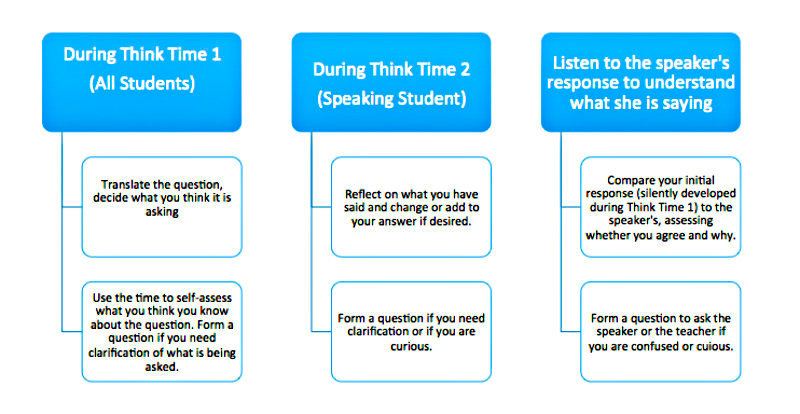

If students are to question orally during class, they must have the chance to enter the classroom conversation. Routine use of Think Time 1 and 2 provides the opportunity for students to form their questions and make their bids to pose them.

Think Time 1 is the 3-5 second pause following a teacher question before naming a student to respond. This pause enables students to consider and to ask about the meaning of the question when appropriate. Think Time 2, the 3-5 second pause following the end of a student’s comment (prior to anyone else speaking) provides the opportunity for students to process what a speaker has said and pose questions about the speaker’s comment or about the topic in general.

Teachers can also use pauses during direct instruction to afford time for student processing and questioning. Before the pause, ask “What kinds of questions do you have?” (a much better prompt than the usual, “Do you have any questions?)

Another strategy I recommend to teachers is to institute a policy of “raise your hand to ask a question—not to answer the teacher’s question.” This enables the teacher to use a more equitable response structure while also placing value on student questions.

The common thread running through all of these techniques is the interruption of teacher talk long enough for students to be able to think about and pose their own questions.

5. Create a culture that values student questions

None of the above strategies will take off in a culture where students are afraid to take risks – to make themselves vulnerable. Many students believe that by asking a question they are admitting their own ignorance. Teachers must be intentional in communicating to students that their classrooms are places where questions are valued even more than answers. “Curiosity is celebrated here!”

Let your students know that by asking clarifying questions, they are not only improving their own understanding but helping other students in the class community. We communicate this message not only by what we say, but also by our non-verbals and our actions.

Positive verbal feedback is an excellent way to bolster this message. Imagine the impact of a teacher statement such as, “I really appreciate the thoughtful question that Maria asked earlier. I wonder if others of you have wonderings of your own.” Consider how much more powerful this statement is when the teacher’s tone and tenor communicate appreciation and when she smiles and gestures toward Maria.

Questions help students become leaders of their own learning

Culture can be loosely defined as “the way we do business around here.” With this definition, we can make the case that the first four strategies — Establishing the Expectation, Developing Skills, Offering Practice Opportunities, and Providing Time and Opportunity — contribute to Strategy 5, creating a culture that welcomes student questions.

Student-generated questions put learners in the driver’s seat. They advance both learning and engagement. Add these five strategies to your repertoire to find out if they will result in more student questions. And be sure to share the results—and other questioning strategies you may already be using—with the broader educational community. You can start right here in the comments.

Author and educator Dr. Jackie A. Walsh is a leading authority on using effective questioning to advance learning. She is the co-author, with Beth Sattes, of Quality Questioning: Research-Based Practice to Engage Every Learner (Corwin, 2nd Edition, 2017) and Questioning for Classroom Discussion (ASCD, 2015).

Dr. Walsh is also a lead consultant for the Alabama Best Practices Center, which affords her the opportunity to work in classrooms and with networks of school teams, district teams, instructional partners, and superintendents.

Edutopia has republished portions of this article.

Great stuff! Thanks so much for all of this. Teaching children to take charge of their own learning is preparation for full participation in their lifelong learning.

This article has been so helpful as I plan my next unit. Thanks!

I often teach materials that involve critical thinking and this article is really beneficial for encouraging students to be critical by asking questions.

I often utilize questioning strategies in my classroom that probe students to deepen their knowledge and understanding. However, I would definitely like to see my students asking more questions on a regular basis. Thank you for providing such an in-depth article on specific ways to encourage students to ask more questions. It is truly vital in order for students to become more involved learners!