Middle Schoolers Thrive on Place-Based Learning

As eleven-year-olds, my friend Tammy and I decided to follow the river behind my house downstream about a mile towards town. By the time we hauled ourselves up the riverbanks and into the general store to buy candy, we came to see ourselves as adventurers who understood the river in a way that no one else did.

Around this time, my friend Kristen and I wrote and published a town newspaper, which we sold at the town store for 25 cents a copy. We interviewed interesting townspeople, penned many editorials (although we didn’t know that’s what they were!), and compiled a list of significant past events.

These experiences, combined with my growing concern for “issues” such as animal rights, played an invaluable role in my life as I started to transition into adulthood. My desire to explore and engage grew considerably.

I also craved to take a more active role in the adult community around me. I had questions about how society worked and wondered about my place in it. All of this completely makes sense for that age, a time when hormones and new brain cells kick in and children look around with new eyes.

Middle schools often forego exploration, engagement, and connection

Perhaps recognizing the power of experience during my tweens and teens was one of the reasons I was drawn to become a middle school teacher. Unfortunately, I found that schooling during the middle school years does not often highlight experience, but instead focuses on isolation and specialization.

Students are designated to large buildings filled mostly with peers, loaded up with textbooks, and sent to several different class periods a day where learning is siloed into different subjects.

At the same time – as documented over a decade ago in Last Child in the Woods by Richard Luv – young people are spending more time indoors and are exploring their communities less, whether it be the forest or the main street. The developmentally appropriate tendency towards exploration, engagement and connection is not given fertile ground to grow.

From the onset of my teaching career, I knew that I would not be able to teach in a traditional middle school. Luckily for me, I discovered place-based education and now work at a school committed to these concepts and goals.

At its core, place-based education works to connect children with the places where they live as a way to make learning more relevant and rich. It provides a scaffolding for young people to understand – and care about – the rest of the world. Although there are many ways that place-based education benefits the learning program at any middle school, I will highlight three examples of how the middle school students at our school explore, engage, and connect. I hope readers will find some ideas and inspiration.

Adopt-a-Place Program

Every class at Cottonwood School, our public charter in Portland, Oregon, has adopted a nearby natural area. Our 7th and 8th grade students have taken some responsibility for a property across the river from us called Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge – a fairly large area, containing wetlands, meadow, and forest.

Students take public transportation to the site up to six times over the school year to engage in many kinds of activities. They use the site in the beginning of the year to participate in community-building experiences and practice geography and science-based skills. They meet with representatives from Portland Parks at least two times a year to complete restoration work. As a highlight, they meet their kindergarten buddies there two or three times over the school year to explore, work, and play.

Recently, our middle school science teacher, Chris Wyland, was able to connect his ecology unit to an authentic service project at Oaks Bottom. An ecologist from the city, who knew how much time our students spend at the property, asked the classes if they would collect data specifically on waterfowl, water quality, soil quality, plants, and human use over a three-year period and share regular reports on their findings.

This launched a cross-grade project that further connected students to Oaks Bottom. The first year, they traveled to the site almost every week during the fall and reported to the city ecologist in early winter. In the coming year, a new class will continue the project, using the original data as a baseline.

Time spent at Oaks Bottom is something that our middle schoolers will always remember – whether it is a memory of planting a tree with their kinder-buddy, or monitoring geese in the rain, or playing tag in the high grass. Building on the adolescent desire to explore, play, and contribute, teachers in our school are able to foster a love of learning, along with a love of the places where we live.

8th Grade Service Internships

In the spring trimester, our 8th graders leave their classroom one afternoon every week to learn and serve. Students travel in pairs or small groups to different locations in the city, where they will return for 7 or 8 sessions over two months.

Partner organizations have included the Red Cross, local retirement homes, Loaves and Fishes, the Ronald McDonald House, food banks, museums and watershed councils. Internships can also involve working with kindergarten/first grade classrooms, or building benches for the school playground.

Working with the same site over an extended period of time allows students to hone career skills such as communication and self-management, develop a relationship with their site supervisor, and learn more about the organization they are working with.

Through their service internships, students develop a sense of agency. Their skills and talents are recognized, and they feel like valued members of the wider community outside of their classroom. One retirement center requested that a group of students offer “technology coaching” for their residents. The 8th graders set up in the computer lounge and served as “experts,” giving tutorials on how to use smartphones, tablets, and laptops.

One 8th grade boy, who struggled socially, returned from his internship in the kindergarten with a tremendous smile and an armful of love letters from his students. Another boy, who interned in the memory care unit of a retirement home, developed such a strong bond with the residents – so much so that he continued to volunteer throughout the summer.

Again, these experiences give students a better understanding the world and their role in it. When students have opportunities to give of themselves to people and places around them, it reinforces their own competence and worth, while strengthening the connection they feel to their community.

Place-based Projects

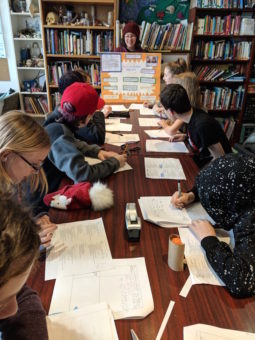

In the classroom, our students engage in three large projects a year. The projects are primarily based on social studies and science standards, and heavily integrate language arts and career skills. Using projects as a vehicle for learning further provides opportunities for students to explore, engage, and connect by incorporating community partners, authentic products, and student choice. Below are just a few examples of some recent projects:

As part of a unit on immigration, students planned and hosted a naturalization ceremony at our school.

- Students interviewed owners of local businesses to learn about how Portland is connected to the global economy. Interviews were turned into podcasts and played by a local radio station.

- Students worked in small groups to complete service projects for the local community garden as part of a unit on agriculture.

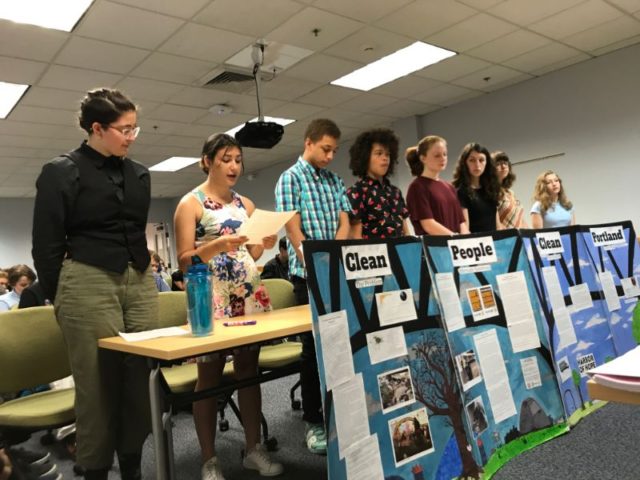

- Responding to Portland’s high houseless population, students researched current policy and issues. The class collaborated to write and present a proposal to the mayor on the need for mobile sanitation units.

- Students interviewed community members about storms they had experienced. Students then worked with climate scientists from local universities to “unpack” the data around the storm to understand how weather and climate work. Interviews and research were put together into a public presentation.

Through projects like these, our students engage with content that is relevant, interact with expert guest speakers, conduct numerous fieldwork trips, and find themselves connecting with their community again and again. Instead of learning through siloed content-areas, projects more closely emulate real life, where all subjects are integrated.

Students often create products for an audience outside of the classroom, inspiring them to complete high-quality work. At the end of a project, they have something to celebrate: not only have they increased their content knowledge and strengthened academic skills (such as research, public speaking, data collection, etc.), they have applied their learning to help, to teach, and to give back.

Schools and communities are ready for place-based education

These days, the ideas behind place-based education are being discussed in more schools and communities. And it is no wonder. After years of test-driven instruction, both teachers and students are looking for better ways to learn.

In middle school, applying the lessons of place-based education is not so much a matter of a revolutionary shift – it’s more a matter of tuning in to what kids this age really need. Giving more opportunities for our adolescent students to explore, engage, and connect will ultimately improve learning because it is developmentally appropriate. The fact that it is also more fun is only evidence that we are getting something right.

_______________________________________

Before teaching in the classroom, Anderson spent many years as an educator in non-traditional settings: she served as a Community Outreach Coordinator for Metro Parks and Greenspaces in Portland, she taught job skills to local high school students on a farm in Vermont, and she worked as a teacher naturalist in the California Redwoods. She has written for Teaching Tolerance, Educational Leadership, and Community Works Journal and her work has been featured by Yes! Magazine. She lives in Portland with her husband and son.

Visit her website and follow her Facebook page to learn more about place-based education activities.