Why Afterschool Matters for Students in the Middle

It is well known that afterschool programs keep kids safe, inspire them to learn, and give parents peace of mind during the often-perilous hours after the school day ends and before parents return home from their jobs.

That’s why public support for federal funding for these programs is sky-high. Most people, however, associate afterschool programs with elementary school students. Less well known are the afterschool and summer programs that serve middle school students, which play a critically important role in putting them on track to succeed in school and in life.

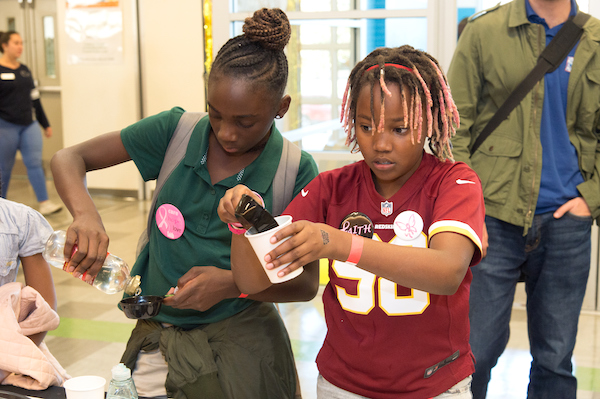

Research has shown that for traditionally underserved and at-risk middle school students, more learning opportunities are important. Quality afterschool and summer programs are uniquely positioned to provide hands-on opportunities to learn that are educational, engaging and fun. This additional learning time leads to greater achievement, better school attendance, and more engaged – and ultimately successful – students.

After-School All-Stars (ASAS), which since the mid-1990s has run programs that serve tens of thousands of students, the majority of whom are in middle school, is one of the best-known providers.

The New York Life Foundation, too, has recognized the importance of after school support for middle schoolers and has invested heavily in programs that help build academic foundations that help prepare these students for the transition to high school.

The foundation’s Aim High grants to local organizations help economically disadvantaged eighth-graders get to ninth grade on time and prepared for high school level work. In fact, since 2013, the Foundation has invested more than $38 million in national middle school out-of-school-time efforts.

Why Focus on Middle School?

The National Education Association has published a tool that says the 13-year-old brain “is just discovering the higher peaks of thinking. And its owners are ready to explore, understand, and maximize their developing abilities. Young people experience tremendous brain growth during the adolescent years.”

That’s one reason most ASAS programs serve middle school students, says Carlos Santini, the organization’s national vice president for programs. Students that age are undergoing the second largest episode of brain development in their lifetime, he says, which creates a need to help middle school youth develop and hone their decision-making skills, personal identities, social connections, and attitude toward academic and career pursuits.

ASAS programs aim to do just that. Marissa Castro Mikoy, executive director of ASAS North Texas, which serves 850 students in five middle school-based afterschool programs, notes that serving middle school youth presents challenges as well as opportunities.

“With younger students, you have a captive audience, but with middle school students, you have to be relatable, earn trust and provide content that is both engaging and fun,” she says.

ASAS North Texas meets that challenge by providing STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics) and healthy living clubs that focus on music production, coding, gardening, photography, cooking, spoken word, 5K running and other activities, as well as snacks, homework help and tutoring.

The program organizes field trips and creates opportunities for students to meet professionals from various fields. Students often are surprised to discover that “someone who looks like me” can hold a high-level job in engineering or another field. “It opens their eyes to all they can do in life,” Castro Mikoy says.

One of the secrets to ASAS’ success is listening to student voices when designing program experiences and making activities culturally relevant. “Embedding school and community culture is a strategic way to ensure that our programs truly represent their students and neighborhoods,” Santini says. All ASAS programs provide classes and activities in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math), career exploration, the visual and performing arts, health and wellness, and academic readiness.

Breaking Through in Boston

Similarly, Breakthrough Greater Boston provides its students with time with peers, homework help, and clubs focused on coding, chess, boxing, and much more. It also gives students the chance to join hands-on STEAM workshops that cover such topics as chemistry of cooking, digital photography, and engineering, according to its executive director, Elissa G. Spelman. Students visit local labs and conduct experiments there.

The goals of the program, which serves more than 500 students on three Boston-area campuses, are to ensure students’ college access and success, as well as to train the next generation of urban teachers – college-aged teachers-in-training staff Breakthrough.

“This is the time when students are forming their identities and reinventing themselves,” Spelman says, so Breakthrough helps them build strong peer relationships, exposes them to college and careers, and helps them make good choices about how they spend their time.

Most students at Breakthrough, which received a two-year New York Life Aim High grant to expand its services, put themselves on a college track – a major sign of success since most of the program’s youth are Title I, of color, low income, first generation to go to college and, in many cases, from immigrant families.

Partnering and Data-Sharing with Schools

All Breakthrough Greater Boston programs are school-based and its staff members work out of the schools, which gives them continual access to students, teachers and administrators. The programs aim to be as integrated as possible with the school district, as well as with family members.

After its summer program each year, Breakthrough shares the results of pre- and post-summer-program testing with school day teachers, and each Breakthrough teacher writes a letter detailing each student’s summer progress.

Breakthrough also gets releases from family members, which gives its staff access to the school’s online database so they can see a student’s grades, attendance, behavioral reports, test scores and more. Breakthrough conferences with family members and school partners to discuss each student’s needs and progress. “We build in a lot of touch points,” Spelman says, noting that schools sometimes turn to her staff for help getting a parent to engage or to figure out what might be troubling a student.

The vast majority of ASAS programs are school-based as well, which helps them stay connected to parents. All its programs include core day teachers as afterschool staff, recognizing enormous value in their knowledge of students, academic expertise, and practical classroom techniques.

Castro Mikoy says her ASAS program in Dallas values its partnership with the schools. “We let them know we’re here to be a partner, not a service provider,” she says. Her program, too, has a data-sharing agreement with the school district that allows afterschool staff to see records on each student’s attendance, grades, behavior and test results in real time.

“Often there is a need for social/emotional support when navigating difficult situations teens face, like cutting, bullying, or sexual identity,” she says, “and we can provide positive adult role models they can go to.”

Afterschool Program Challenges

Despite the success of many afterschool programs in boosting achievement for middle school students, challenges remain.

Middle school afterschool program providers struggle with sustainability and funding, in particular because one- and two-year grants force them to search for resources year after year. There is a scarcity of resources to provide the professional development that afterschool program staff need.

When schools are focused on improving test scores, they may not be able to partner as fully with afterschool programs as they otherwise would or to provide a liaison who is truly dedicated to supporting the afterschool program.

“Middle school is the forgotten age,” Castro Mikoy says, “for communities and for our society. We focus on kindergarten readiness, third-grade skills, and high school graduation. But middle school is a really critical time for lots of kids who have great potential but are at a crossroads.”

The Afterschool Alliance is carrying that message to Congress, to lawmakers at all levels, to the business and philanthropic communities, and to the public at large. More attention to – and resources for – middle school programs will help students, families, schools and communities, improving our workforce and our economy over time.

____________________________

Jodi Grant is Executive Director of the Afterschool Alliance, a nonprofit public awareness and advocacy organization working to ensure that all children and youth have access to quality, affordable afterschool programs. Prior to assuming her current leadership role in 2005, Grant served as Director of Work and Family Programs for the National Partnership for Women & Families and as a general counsel and staff director in the U.S. Senate. She graduated from Yale University and received her law degree from Harvard University. As a student, she volunteered in afterschool programs.