Real Media Literacy: Spotting a Fake Story

Do your students know how to “read” a news story they’ve come across on a website or in social media and evaluate the information the creators have presented?

Increasingly today, the ability to analyze and evaluate the techniques by the fake news creators is more important than ever. But are students receiving sufficient coaching and practice in questioning what they read?

Reading Laterally

Experts are now recommending that students read laterally, as opposed to vertically. Lateral reading involves “the act of verifying what you’re reading as you’re reading it.” (Source)

For example, imagine you come across a data point on screen-time for children. Maybe the statistic sounds far-fetched (e.g., “Children ages 8-14 spend an average of 12.6 hours a day staring at a screen). Instead of continuing to read by either accepting the data without consideration or being skeptical and eroding the credibility of everything else you read from then on, ‘lateral reading’ would have you stop and fact-check that data point. (TeachThought)

Researchers from Stanford University agree and say that today’s students must become like fact checkers. They observe that “lateral readers don’t spend time on the page or site until they’ve first gotten their bearings by looking at what other sites and resources say about the source at which they are looking.” (Source) Want to know more? Download the free eBook Web Literacy for Student Factcheckers.

Deconstructing Any Media Content

Those of us in media literacy have recommended students ask these questions about all media messages, including those online:

- Who is the author/creator? Can they be contacted?

- Who is the intended audience? How do you know?

- What techniques does the author use to make it authoritative or credible?

- How might other people understand this message differently from me?

- Who or what has been omitted and why?

- Who benefits from the media message?

- Where was the message published and who is likely to see it there?

- Where might I go to confirm or verify the info that I am reading?

These are important critical thinking questions, and you can locate a number of infographics online which use these questions, and others, all of which are designed to jump start student skepticism.

I recommend you post one of these “pay attention!” infographics at every computer at school. See for example the CRAAP Detection infographic or the HOW TO SPOT FAKE NEWS Infographic.

Lesson Idea: Teaching With Examples

Beginning in 2016, a number of news stories about the explosion of “fake news” have referenced the importance of incorporating media literacy instruction in our schools.

Here is an approach I have found useful. I take a “fake news” webpage or site, create a handout from it, and engage either teachers or students in an exercise where they are challenged to identify the techniques used to fool the visitor. In addition, I ask students to consider some media literacy-oriented critical thinking questions about the site and its contents.

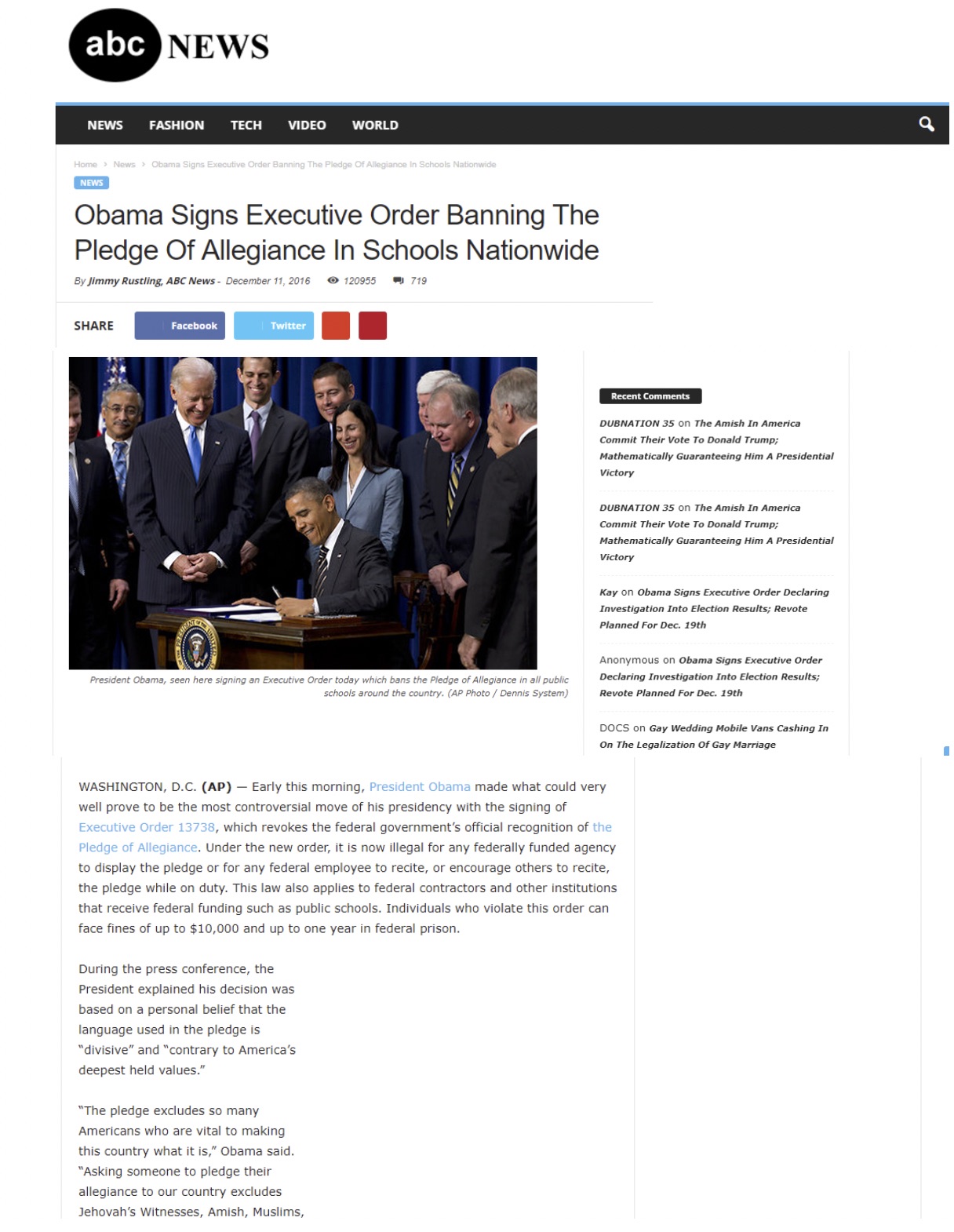

I have converted a notorious fake website page (below) into a one page handout (you can download here) to provide a show-and-tell for you.

Will your students know instantly that this website content is fake? Let’s do some analysis that models the “lateral thinking” strategy.

► Using the Obama “news” story above (click to enlarge), let’s start with the URL address. It is:

http://abcnews.com.co/obama-executive-order-bans-pledge-of-allegiance-in-schools/

The source appears at first glance to be ABC NEWS, but notice the domain name .co indicating the country of Colombia in South America. A quick check on Google shows the real ABC News does not include a country designation in its URL.

► Third, have students locate the name of the author. Is/was Jimmy Rustling a real reporter for ABC NEWS? Do some quick searching to find out.

► Fourth, have students consider the headline. At the time this story appeared online, a reader should have asked themselves: Have I seen, read or heard anywhere else, from any other news source, that the President signed such an executive order? If not, does that make sense? This should be another red flag.

► Next, have your students consider the photo. In this case, it is a real image of Obama signing an executive order. By conducting a Google Image search (using a search string like “President Obama signs executive order”), students may be able to discover the exact image and read the authentic caption associated with it, revealing that this image has been appropriated for false use.

► Readers could also do a simple search for “Executive Order 13738” mentioned in the article and discover at the Federal Register website that the real EO was an amendment to an earlier EO regarding fair pay and safe workplaces. Nothing to do with the Pledge.

► Finally, ask students to notice the dateline, Washington DC, followed by the letters AP, which stand for the Associated Press news agency. By citing AP, a venerable and respected media service, the author again hopes the unsuspecting reader will not question the story’s authenticity. In this case, a quick search of AP.com stories for the date range shown will help confirm it’s a fake.

Another fact-checking source, Snopes.com, described the story as “an old hoax” used by “malware spreaders.” A Google search on the day I’ve posted this article revealed that some extremist websites still present this story as true.

A Healthy Skepticism

With the 2020 election season underway, fake news and deceptive social media posts, photos and videos are expected to become commonplace. It is more important than ever that educators consider how to best help 21st century “digital natives” acquire the critical thinking and “healthy skepticism” skills they will need today and tomorrow to function as citizens.

Other Resources

- New York Times Learning Network. Teaching Activities for: ‘It’s True: False News Spreads Faster and Wider. And Humans Are to Blame.’

- New York Times Learning Network. Student Opinion: Do You Think You Can Tell When Something Is ‘Fake News’?

I like this lesson! One challenge of introducing misinformation to students is how to point them to actual examples without actually sending traffic to sites and users who are purposely trying to deceive people. Your solution to download and share as a PDF gets around that nicely.

Very good article. I use a similar “abcnews.com.co” webpage [copied] about Obama and gun control for a Misinformation, Fake News and Political Propaganda workshop I present at libraries [for adults]. These analytical strategies are so easy and helpful and yet are not taught! We need to do better.