Teaching about Empathy, Boundaries and Consent

A MiddleWeb Blog

Every so often, a confluence of events occurs that gets my wheels turning and the end result is putting my thoughts down on paper to sort them out. This happened over summer break.

Every so often, a confluence of events occurs that gets my wheels turning and the end result is putting my thoughts down on paper to sort them out. This happened over summer break.

In June I was speaking with a colleague who is a principal of a large, suburban middle school. He told me that the design of his school was such that all of the student lockers were concentrated in one small area and all students needed to access them at the same time.

This was a problem he was trying to solve for the upcoming school year because it was becoming a gauntlet of sorts that students were loath to navigate due to the close proximity and the unwanted (and, in some cases, wanted) physical contact that occurred.

Shortly following this conversation, a friend told me that her 13-year-old daughter was devastated because she and her friends had found out that some boys at her school had a group text where they were discussing which girls were “hot” as well as other more graphic details. Her daughter had been labeled “not hot” and terrible things were said about the girls in general.

In July, I had the privilege of hearing Laurie Halse Anderson speak at NerdCamp in Jackson, MI. This year is the 20th anniversary of Speak, her groundbreaking novel about teen sexual assault.

She has written a new memoir, Shout, that not only details her personal rape experience, but serves as a call to action to help stop sexual violence and to help victims find their voices. (Two chapters, “Collective” and “Forgiveness,” are so alarming and powerful that they took my breath away.)

Laurie Halse Anderson recalls the impact of Speak ten years after publication.

Anderson had the nearly 2000 of us in attendance riveted, nodding in agreement, and motivated to lead the charge of doing this work. I spoke to her after her talk and asked for advice about where to start the conversation with my middle school students.

Finally, I just finished the Advanced Reader Copy of Barbara Dee’s new novel, Maybe He Just Likes You, due out in October. In it a seventh-grade girl, Mila, is being targeted and sexually harassed by some boys in school. I won’t spoil the plot, but I feel this will become every bit a must-read text for middle school students as Speak has been for high school.

Teaching empathy, boundaries, and consent

All of these individual events led me to feel very strongly about how we are or are not teaching our middle school students about empathy, boundaries, and consent.

Nearly every adult woman I know, myself included, has her own #MeToo story, and I suspect a large number of men do as well. A lot of the behavior that leads to these situations begins in middle school or even earlier.

I’ve done a lot of reading on the subject, and I don’t have all the answers. But I believe there are a few ways we can do this in middle school before students get to high school and it is possibly too late.

As always, the question of when to try to fit in yet one more thing to do in a day is a real consideration, but I might argue that our advisory and even some classroom time is better spent on these issues than on most others as these events can have lifelong consequences.

How educators can help

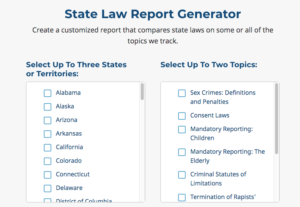

First, in my conversation with Ms. Anderson, she recommended that I find out the laws for my state regarding consent as well as to look into the sexual harassment policy, if any, that exists at my school. RAINN, the Rape, Abuse, & Incest National Network, has a great resource where you can find out how your state defines consent. And it should not be too difficult to find out your school’s policy on the subject.

Second, we don’t need to dive into discussing how to report sexual assault at the beginning of sixth grade. We can begin by continuing our current anti-bullying lessons and specifically targeting the topics of respect and boundaries. There are numerous, high-quality ready-made curricula out there – some of them are even free – to help schools and teachers navigate these conversations in their advisory groups and classrooms. (See resources below.)

I get so frustrated by the many attacks on schools that we see in the media along the lines of “the teachers/principal/counselor KNEW but didn’t do anything.” I can assure you this is not the case the majority of the time. Perpetrators of misdeeds are not now, nor have they ever been, obvious about doing their misdeeds in front of adults. Students and their parents may assume the teachers or administrators are aware, but this is generally not the case. We need to create a safe environment where students feel comfortable sharing this information.

While it is true that adults are often unaware of things such as student’s touching other students inappropriately in the hallways, writing inappropriate graffiti on restroom walls, inappropriate group texts, and the like, when we do hear or see something, it is our duty to do something about it.

If you hear someone being called a “fag” or a “slut,” this is the time to teach students that words matter and that kind of language will not be tolerated because it is hurtful. (Of course, this will be ignored if you are not also doing the background work to establish relationships and teach about respect, empathy, and boundaries.)

If you witness a student touching another person’s belongings or even the person themselves, ask if they had permission. That’s a boundary issue. If a student reports that they are uncomfortable or concerned about something happening to them, take them seriously. Do not dismiss it as “boys will be boys,” or “it’s because he thinks you’re pretty,” or “typical mean girls,” or “locker-room behavior.” None of it is acceptable and should be dealt with using both education and consequences.

Resources

As I said, I don’t have all the answers, but there are some wonderful resources out there which can help.

Laurie Halse Anderson at Mamaia

“Consent at Every Age” by Grace Totter at HGSE

“Teaching Consent Doesn’t Have to Be Hard” by Beth at Teaching Tolerance

“We’re Teaching Consent All Wrong” by Sarah D. Sparks at EdWeek

#MeToo at Puberty: The Wonder Years

“Shifting Boundaries: Lessons on Relationships for Students in Middle School” by Nan D. Stein, Ed.D.

Thank you for the always-needed support and links to resources.