Breaking Out of the White Teacher Bubble

A MiddleWeb Blog

It’s a powerful punch of a book, no more than 96 pages, instantly gripping and accessible to kids in my highly diverse classroom of that time.

I believed strongly in the need to remind our pre-teens that education was not something they could take for granted, and so we wrote essays on the transformative power of literacy.

I also knew kids needed to be wise about multiple modes of narrative portrayal, so we also critically viewed the film based on the book. And I was a theatre-trained lit geek and committed proponent of hearing fluent models of text, so I read the whole book aloud. With voices.

I can only cringe now.

I meant well. But meaning well and teaching well are not the same thing. This is one of the painful truths that my exponential learning about race in these troubled times has taught me: the difference between intent and impact.

Good intent isn’t enough

What this means in a nutshell is that as a privileged white middle class woman (which most public school teachers are), it is my responsibility to make sure that my intent as a teacher does not ever skew my perceptions of my impact as a teacher.

We instead must exercise all our creativity, our bravery, and our empathy to break out of the white bubble we teachers almost certainly live in.

This process is no fun. It hurts, it’s embarrassing, and for me, it sometimes touched an even deeper pool of resentment because I was a teacher. I had, after all, dedicated myself – my earning potential, my physical health, my life – to the well-being of kids. Didn’t this buy me some credit?

What I had to learn was that this very question – one that presupposes that equity is a luxurious matter of merely earning “credit” in the eyes of the community of people of color – is one which can only be asked by a teacher in the bubble.

Here’s a few questions I wish I would have asked instead, prior to implementing our Nightjohn unit.

- What would it have been like to be a kid of color in this ELA classroom, listening to a white woman attempting to imitate a Southern black accent?

- What would it have been like to be a kid of color in this ELA classroom, reading a book about the black experience of slavery – however powerful the book – written by a white man?

- What would it have been like to be a kid of color in this ELA classroom and have Nightjohn be the only portrayal of black people in the entirety of the year – a portrayal that focused solely on black oppression, painful history, and historical exclusion from education?

- What would it have been like to be a kid of color in this ELA classroom and hear the teacher position, and tacitly dismiss, slavery and its consequences as “things of the past”?

- What would it have been like to be a kid of color in this ELA classroom and know that the teacher had obviously not consulted the sole black 7th grade content area teacher – who was on her team – about how this unit might be perceived?

- What would it have been like to be a kid of color in this ELA classroom and not have the ELA teacher ask about or acknowledge her students’ color in relation to this unit – not once?

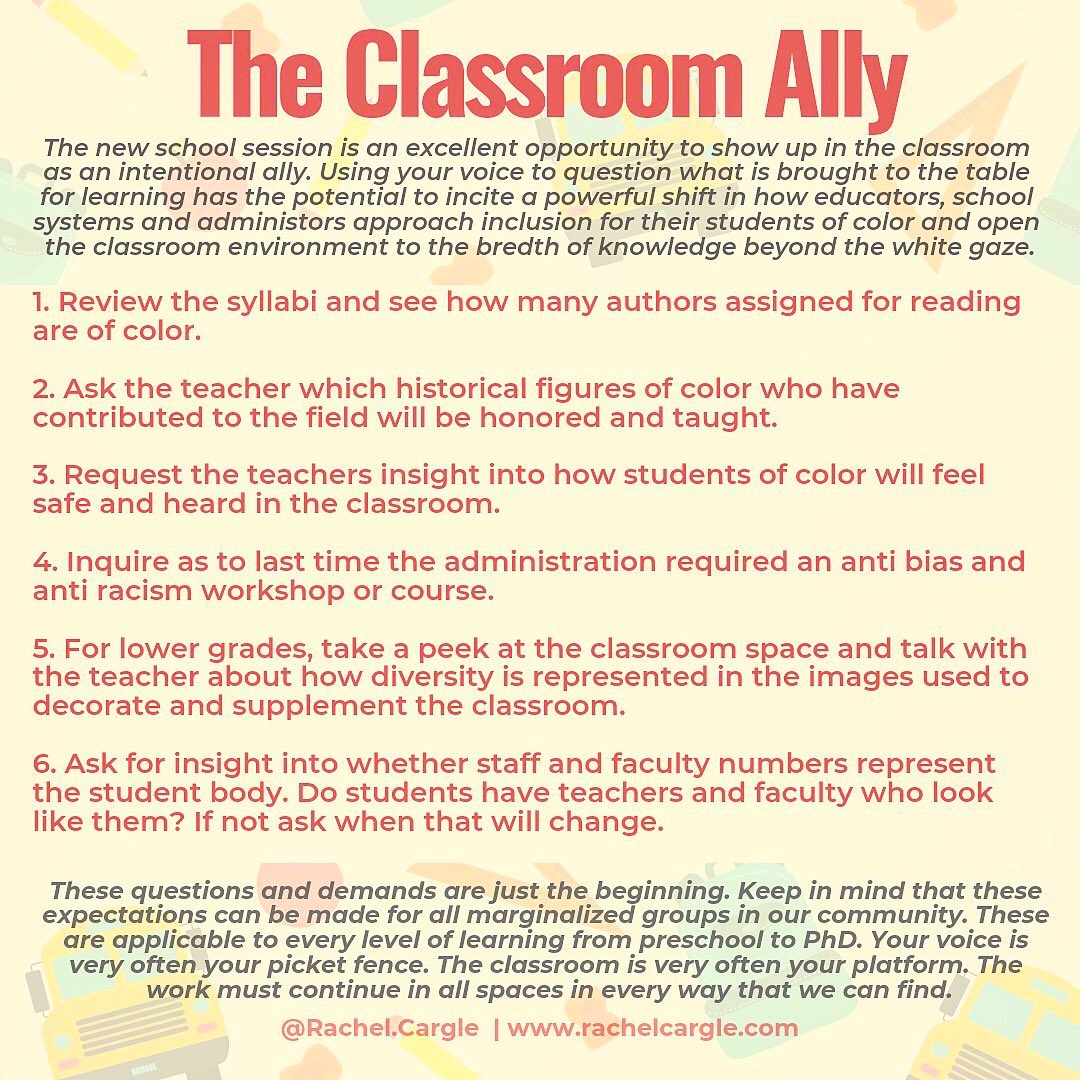

For that good work I can recommend the following checklist of questions by Rachel Cargle, above, public academic and expert on race and culture.

Used with permission. Click to enlarge. (Source)

Where she writes “the teacher,” do this with me: give yourself a pat on the back for coming this far, take a deep breath, and substitute “yourself.”

Thoughtful and courageous reflection, Dina. I find myself asking many of the same questions about my well-meaning lessons “to” instead of “with” students in my early years as a white teacher in an all African-American school. You are correct in your assessment that well-meaning intent does not always equate to desired impact. Ah, to be able to go back and do better this time around . . .

This is a powerful article! As an educator of color and a parent I appreciate your reflection. I also appreciate your attempt to connect with the students. Although your intent was meant well, in my opinion it was the delivery that may have posed the issue with the students and your reflection states that.

Since these are older students I think that you should ask their opinions of how they would feel about certain topics or readings first. When students feel they have a voice in what and how they learn, they have a greater appreciation. Just being a teacher regardless of what you put into education does not “buy credit”. Being passionate and showing genuine concern is what will get students to trust you and even that is sometimes not enough! But, it is a starting point.

The fact that you reflected on the delivery of this lesson has impact!!! Not all teachers regardless of race, color, creed, or belief do this!