Weaving SEL Into Our Classroom Questioning

How does social-emotional learning fit into the work of today’s schools and into everyday teaching and learning? It’s an important conversation going on among a lot of thoughtful educators right now.

Certainly… inevitably…social-emotional learning is “a deeply ingrained part of the way students and adults interact in the classroom” (CASEL).

To gauge whether the interactions in your classroom contribute positively to your students’ social-emotional development, consider the following.

♦ To what extent do our questions offer students opportunities to make personal connections to school learning?

♦ How frequently is each student acknowledged during a class?

♦ How safe does each feel speaking when called upon to do so?

♦ To what extent does feedback to an oral response support and extend student learning?

♦ Do all students have opportunities to practice speaking and listening to one another?

♦ Are students encouraged to ask questions when they are confused?

♦ How often do students engage in collaborative thinking?

♦ Do they learn how to respectfully disagree?

♦ To what extent do students feel valued members of their classroom communities?

Deep-rooted questioning practices still found in many classrooms directly influence all of the above SEL indicators, most often in a negative direction.

Included among traditional practices that have unintended consequences for students’ social-emotional development are

- questions designed to elicit right answers rather than personal responses;

- reliance on hand-raisers to respond to almost all questions;

- valuing right answers more than the thinking behind responses;

- dominance of teacher talk and limited attention to listening; and

- dependency on whole-class, teacher-controlled settings for learning.

Our attention to five principles related to how we question can turn these traditional practices upside down and contribute positively to students’ individual academic self-concepts and to the health of our classroom community.

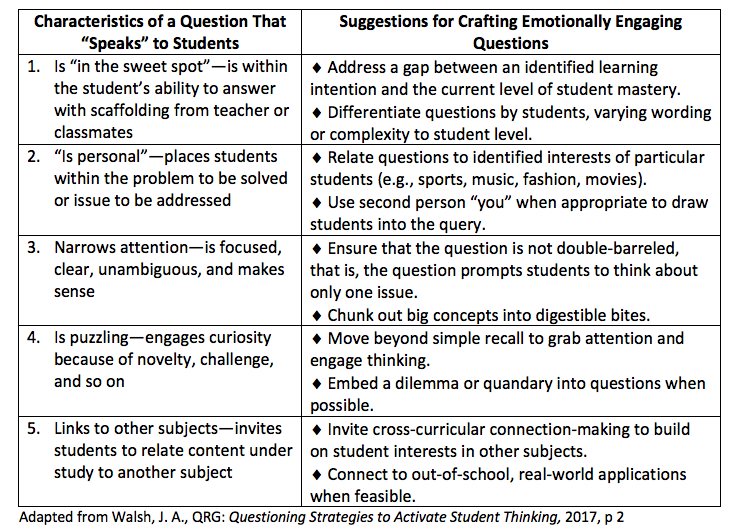

1. Frame questions that “speak” to students

Engaging students emotionally is a key to motivation. Questions that bring students into the query are not only more interesting, they also convey that “learning is about you,” a positive message to send to all students. Think about how the following characteristics might convert a ho-hum, textbook question into one that students might care about.

Advance planning of questions with at least one of these characteristics results in prompts that catch student attention, which is a gateway to thinking, responding, and belonging. Questions with one of these characteristics usually allow for multiple correct responses, one of the threads in the all-important safety net that assures an emotionally secure environment.

2. Focus on responses, not answers

Too often students perceive teacher questions as bids to get the right answer on the floor. This misconception can result in at least two negative consequences for students’ social and academic development: (1) increased anxiety or fear that they may be called on, and (2) lowered academic self-concept.

Changing the way we talk to students about questioning can help modify this long-held perception of the purpose of teacher questions and increase psychological safety in the classroom.

Many students have never thought of the possibility that teachers ask questions to learn about where students are in their learning. They are conditioned to believe that they should volunteer to answer only when they are sure of the answer.

To break this pattern, teachers can plan a short lesson focused on the purpose of questions. The dialogue within this lesson might begin with this teacher question: “Why do you think teachers ask questions? Take some time to think and jot down what comes to your mind.” [long pause] The teacher might then ask students to select the one of the following that best matches their perceptions:

(a) To find out if students know the right answer;

(b) To encourage students to think;

(c) To find out if a student is paying attention;

(d) To assess whether students understand, and to provide appropriate assistance to those who don’t.

Imagine that a majority of students select option “a,” which usually happens. The teacher can then surface reasons why this response was so frequently chosen and engage students in a discussion that leads to a better understanding of the purpose of questions.

The intended message is that everyone’s thinking and responding are important. For students who are confused or don’t yet understand, responses provide a window into the missing knowledge or points of confusion. For students who have a correct understanding, responses invite elaborated thinking, not just a guess at what the teacher would settle for. The hoped-for student responses to the above poll are “b” and “d.”

3. Use all-response or collaborative response systems

Expecting every student to listen and respond, at least silently, to every question is a powerful way to communicate that they and their thinking are important. Providing a vehicle for all to express their response strengthens this message by building in accountability. All-response systems are appropriate when questions call for responses at the Remember (DOK 1) level.

Traditional measures include work samples (e.g., on dry-erase boards), signaled responses, and choral responses when appropriate. Today teachers can also choose from a wide array of electronic response systems—from clickers to platforms that accept open-ended responses. These systems provide anonymity (from other students) and therefore a measure of safety.

Think-Pair-Share is another tried-and-true and highly productive response structure when aligned with instructional purpose. This is more effective when teachers carefully match students, taking both academic and personal factors into consideration.

Think-Pair-Share works best when the following conditions are met:

♦ Students are afforded 1-2 minutes for silent thinking prior to pairing up (Think).

♦ Teachers direct the turns of talk. For example, by timing the talk of each partner (Pair).

♦ Finally, checking for understanding occurs in the last stage (Share) when the teacher calls on students to share their partner’s thinking.

This protocol is very versatile – appropriate for questions at multiple levels of cognitive demand.

Both of these approaches contribute to increased self-awareness, the component of SEL that CASEL associates with a “well-grounded sense of confidence, optimism, and a growth mindset” by providing students opportunities to test their understandings in a safe environment and revise their thinking by referring to peer feedback.

Think-Pair-Share also develops important relationship skills including these identified by CASEL: “Communicate clearly, listen well, cooperate with others, negotiate conflict constructively, and seek and offer help when needed.”

4. Move from evaluative to interpretive listening

John Hattie (2011) reports that “the most important task for teachers is to listen.” He further writes that teacher talk occupies most of the air time in classrooms with student responses to teacher questions averaging 2-3 words—or less than 5 seconds—70% of the time. Dylan Wiliam (2018) recommends moving from “evaluative listening” (listening for the correctness of an answer) to “interpretative listening” (carefully attending to what students say to learn about the thinking behind their comments).

Interpretive listening, which is supported by classroom use of think time, opens the door for follow-up questions that can provide additional insight into student thinking. Useful prompts include, “What makes you say that?” “Please say more about . . . I’d like to get behind your thinking,” and similar queries.

Interpretive listening provides evidence of a teacher’s interest in responses, not answers, and develops both academic confidence and self-management (a third component of CASEL’s Framework) by motivating students to achieve academic goals.

5. Increase opportunities for student dialogue

As students develop confidence in themselves as learners and become more secure in their classroom environments, they develop the readiness to move into robust student-to-student discussion. In this arena students are challenged to use questioning practices to direct their own learning and to learn with their classmates. Productive discussion depends upon both skills and dispositions, which must be taught, not assumed.

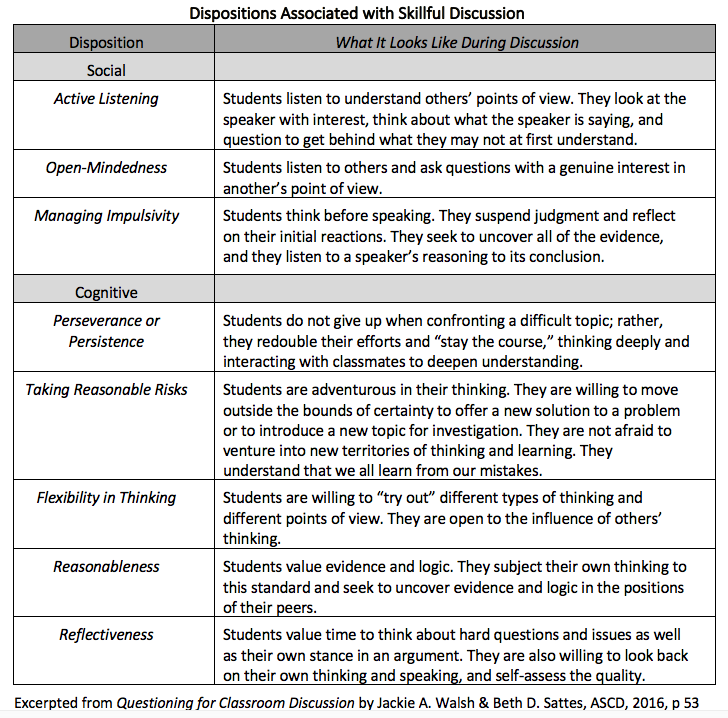

Important skills for discussion include active listening, respect for divergent points of view, questioning to clarify, and building on one another’s perspectives, to name but a few. Dispositions – student attitudes or ways of thinking about interacting with others developed through discussion – strengthen students’ social awareness (i.e, understanding the perspectives of others) and relationship skills.

The chart below spotlights some of the dispositions that can be developed through discussion when teachers are explicit about what each means and why it is important.

Good reasons to abandon tradition

Traditional routines can convey unintended, often subtle messages to some students that their learning is not as important as that of others and that they are not “smart” enough to engage in classroom conversations monopolized by their seemingly more able peers. These perceptions undermine social-emotional growth as well as academic learning.

Weaving new patterns of questioning into daily practice can help transform learning settings into safe and supportive environments where all students have an opportunity to grow socially, emotionally and academically.

References

CASEL (2019). “What is SEL?” https://casel.org/what-is-sel/

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible Learning for Teachers. Routledge

Walsh, J.A. (2017) QRG: Questioning Strategies to Activate Student Thinking. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Walsh, J.A. & Sattes, B. (2016). Questioning for Classroom Discussion. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Wiliam, D. (2018). Embedded Formative Assessment. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

_______________________________

Dr. Walsh is also the lead consultant for the Alabama Best Practices Center, which affords her the opportunity to work in classrooms and with networks of school teams, district teams, instructional partners, and superintendents.