How Not to Go Crazy Reading Rough Drafts

A MiddleWeb Blog

Here’s a bit of a confessional. For many years, with major writing assignments, I avoided reading my students’ rough drafts.

Here’s a bit of a confessional. For many years, with major writing assignments, I avoided reading my students’ rough drafts.

I thought I didn’t have time – and that if I commented on the rough drafts I would be doubling my paper load. I envisioned slogging through paper after paper, then having to trudge through them all again, like trampling on dirty snow.

Earlier in my career, I actually did do that slog, for nobility’s sake, and later thought: No way.

I might have continued this dance of avoidance indefinitely, until I realized (a little late to the game): If students don’t receive and process meaningful comments on rough drafts, whether from me or their peer responders or both, their final papers will read like rough drafts.

In fact, giving comments only on final drafts can actually be worse than giving them on rough drafts. Because, unless we ask students to do corrections or respond to our comments, the comments we make will – as we well know – disappear into the ether, never to be recovered.

Lots of effort on the part of the teacher. Little learning on the part of the student. This is not a zero-sum game: It’s actually negative when you look at the wear and tear on us as teachers.

So, what I’ve ended up doing in recent years with research papers is to grade rough drafts deeply, grade final drafts hardly at all – and, crucially, structure the writing so that rough drafts become something I actually want to read.

Something Needed to Change

The final tipping point in convincing me to read rough drafts came more recently than I’d like to admit, when I yet again dug into a set of final eighth-grade U.S. history research papers and realized that if I wanted to be teaching writing in history class – which I very much did – this was not the way to do it.

The papers were well sourced, and many of them had strong thesis statements because we had worked on them in class together.

Yet the writing in many instances simply didn’t gel. A lofty topic sentence bore little relation to the evidence within the paragraph. Quotations were not always embedded well, and facts were not sufficiently paraphrased. Vague words such as bad, good, great, and sad carried the day.

These papers were not long – about two pages, double spaced – but they felt like it. Grading them while sitting next to a hotel pool on spring break made me want to toss them into the water. In my lesson plan file I wrote, in huge red font so I wouldn’t ignore it: “Do whatever it takes for this not to happen in the future!”

Then I schemed for next year.

What if I could give students enough scaffolding, through an outline organizer and accompanying peer response, that their rough drafts included everything I wanted?

What if I could then write copious comments on the rough drafts and ask students to incorporate changes into the final?

And – best of all – what if I barely graded the final drafts, since all the of the meaningful work would have happened before that?

Four Steps that Keep Me Sane

To accomplish this scheme, here are the four steps I implemented that made me feel, for the first time, that these research papers were a process, not a fait accompli: that I was actually helping rather than simply grading my students.

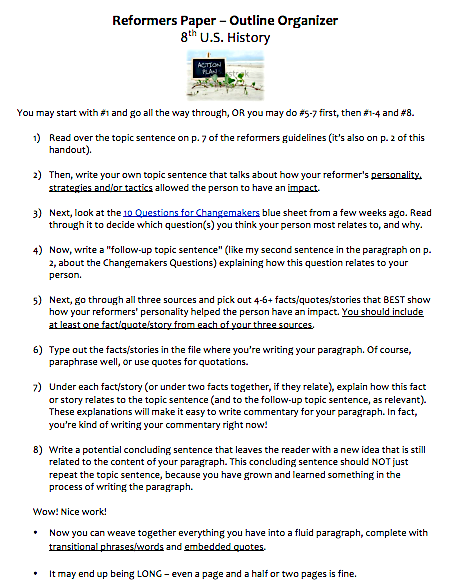

1) Create an excruciatingly detailed outline organizer that students can use while constructing their papers.

This organizer took several days for most students to complete in class. By the time they finished, they were effectively done with their rough draft. Download the organizer and the model paragraph here.

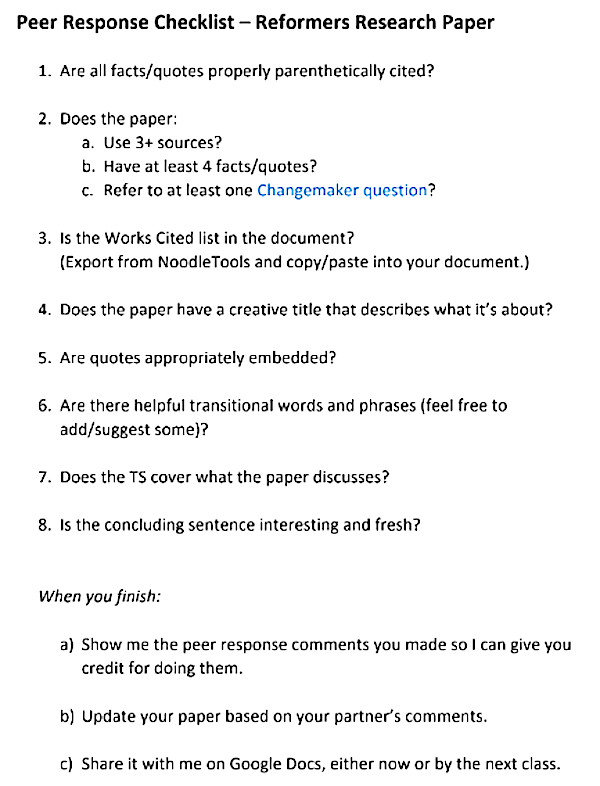

2) Make sure the peer response criteria for the rough drafts correlate with the outline organizer.

One of the best tricks I’ve learned in recent years is to make peer response more like a checklist, less like editing. Sometimes I’ll include questions that ask about coherence of argument, but mostly I’m asking kids to help each other double-check the details. Download the peer response guidelines.

3) Comment on the rough drafts myself, ideally in Google Docs, and then require students to address all comments for the final draft.

Like many of us, I try to grade electronically whenever possible now. It makes my comments easier to read, and students say they enjoy responding to comments more onscreen than transitioning from paper to screen. I also find they often put more effort into responding to a Google comment than a written one.

As one student wrote in an anonymous survey this spring about responding to my online comments, “Getting comments on Google Docs makes it not only easier to find where you need to fix your mistakes but also gives the teacher more space to write about what they’d like you to change. Having all of my suggestions laid out in front of me makes it easier to find, replace, and add things to my writing piece.”

4) Grade the final draft only on whether students worked hard to address all my comments.

The beauty of commenting in Google Docs is that, when grading the final draft, all I do is click on the document history and do a quick scan to see that students have made a good-faith effort to improve their papers.

That’s it! I’m not grading for quality, because I’ve already done that on the rough draft. Here it’s just on effort and time spent. This becomes an incredibly quick grade, and I usually don’t make any comments on the paper besides a general “good effort” at the end, if they’ve tried to address all my concerns (and most have).

If you prefer grading on paper, you can ask students to highlight major changes they’ve made from the rough to the final draft, which creates the same outcome as a Google document history.

Relief, Finally

With this outlining and grading process in place, I feel that I’m truly, finally helping students with their writing. Not simply providing a scattering of never-read comments on their final drafts. Not simply doing mini-conferences as they’re composing on their laptops. But examining their ideas word by word, noticing the nitty gritty, so that their language (at last!) can rise to the level of their ideas.

See Sarah’s July 2020 wrap-up post

about her Reformer’s Project here.