Shining the Light of Truth: Teaching Black History All Year Long

A MiddleWeb Blog

The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them. – Ida B. Wells

The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them. – Ida B. Wells

The end of this past school year, and the events surrounding the death of George Floyd while in police custody, have left all of us reeling.

For those of us who teach U.S. history, there is so much advice, so many suggestions from so many well-meaning individuals and organizations, so much to read. And more to read. I have gotten more links to lists of books to read about racism in the last few weeks than I can count.

But may I suggest that, for history teachers, what Dr. King described as the “urgency of now” demands we read as much about the past as the present?

Whenever I get overwhelmed, I go back to what matters most to me as a teacher. And right now, that means rethinking my curriculum to include more Black history than I already do. I teach 8th grade U.S. history picking up from after Reconstruction. I can imagine that what my new students understand about Reconstruction will be shaky due to remote learning.

So I am considering starting off the year with a review of the Reconstruction Era and how it is an unfinished process in our country.

We must remember that African American history is not all about slavery, but that slavery had a profound impact and reach that continues today. (See the end of this post for resources on that continuing impact via the 1619 Project.)

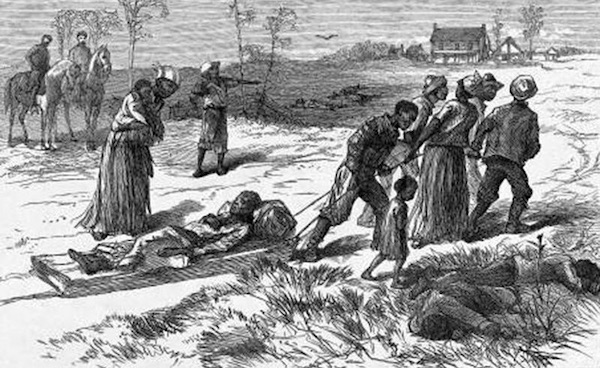

We must remember that when we do teach about historical slavery, we can’t wait to teach it until right before we get to the Civil War unit. We must teach students about the enormous impact of slavery on the story of America from its very beginnings.

And when we wrap up our units on the Civil War and Reconstruction, we can’t ignore Black history until Rosa Parks. None of us – no matter our race or the race of our students – can afford such a distorted view of history.

If we are intentional about doing the work that social justice advocates are talking about right now, we will be busy. We will struggle this summer as we get ready for fall. Lonnie G. Bunch, Secretary of the Smithsonian, concluded his recent statement on racial violence and division with the quotation below.

If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. – Frederick Douglass

Why Students Need Black History All Year

Editor’s note: The remainder of this article first appeared on 9/17/19, and some comments date from then.

In the month of February you will find countless articles about Black History Month. One of the many suggestions you see in those articles is that Black history should be taught all year, which is why you are reading this in September.

In my classroom, we are newly back to school, and we cannot wait until February. Carter Woodson, the founder of what started out as Black history week, hoped that one day the need for such a special designation would disappear – that one day the history and contributions of Black people would be fully embedded in our classes.

I don’t think we’re at that point yet. How could we be when we still read stories about misguided teachers holding slavery simulations in their classrooms or asking students to identify slavery’s positive aspects?

But in my classroom I am working hard to reach Carter Woodson’s goals. The district where I teach has been wrestling with issues of equity that center around race with a new urgency during the past few years. As a result, I have been to a number of workshops on this issue.

These workshops and my own reading and experience confirm for me, a white teacher, that at least part of the answer is to be found in our curriculum. I cannot single-handedly close the achievement gap or end racism, but I can focus on Black history.

Black History Is for Everyone

Among my own students, 55% are white and the next largest group is African American. But whatever the racial makeup in a school, ALL of our students need Black history.

Why? Let me suggest four reasons, with three caveats.

Reason 1: U.S. history makes no sense without African American history.

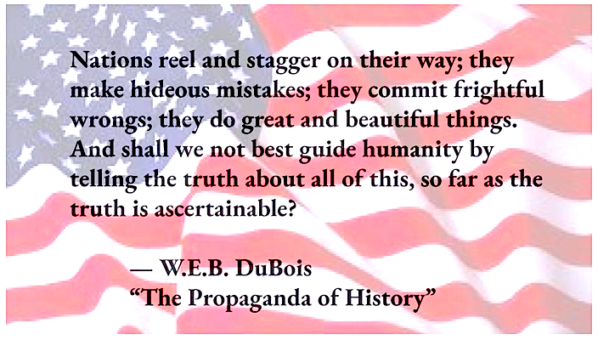

As W.E.B. Du Bois famously wrote, “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.” The twenty-first century, so far, does not appear to be much different.

The color line, beginning with slavery, has informed every aspect of our history. Slavery is THE fundamental contradiction in our country’s history. Our nation’s founding principle – a dedication to the proposition that all men are created equal and endowed with certain unalienable rights – is in direct conflict with slavery.

Our country was built with slave labor, we went to war over slavery, and we have not yet made good on the promissory note Martin Luther King spoke of in 1963. As Nikole Hannah-Jones recently asked, “What if America understood…that we [African Americans] have never been the problem but the solution?”

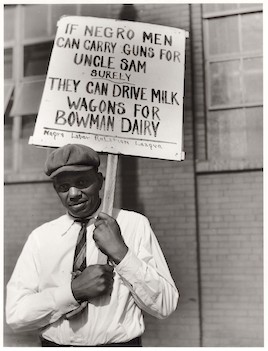

While our country espouses the ideals of democracy, liberty and equality, we haven’t lived up to them, and yet ironically, it is Black Americans who have been the “foremost freedom fighters” in our history. Understanding this contradiction is one of the keys towards understanding the history of the United States of America.

Reason 2: African American history intersects in every unit and period.

Even after your class gets past Reconstruction, African American history continues to play an important role. The Jim Crow era, during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, and the Civil Rights movements are the obvious spots, but African American history fits EVERYWHERE.

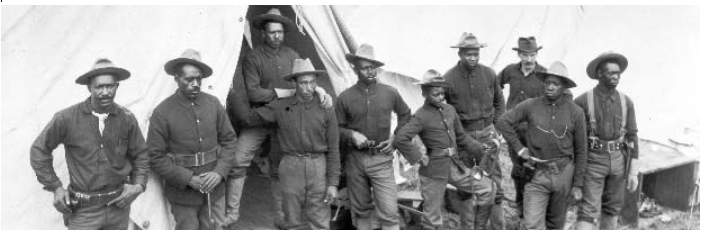

As I have taught different grades, I have found myself at different points in the curriculum during February, which has led me to research and then teach different aspects of Black history. A few years ago, I found myself teaching about the Spanish American War and the annexation of the Philippines during February. At first, I didn’t see how I would find a connection there. But find it I did. African Americans fought in the war, many because they hoped it would prove they were loyal Americans.

This would be true of every war the U.S. has ever fought, beginning with the American Revolution and the death of Crispus Attucks during the Boston Massacre. Interestingly, some Black Americans pointed out the hypocrisy of fighting to acquire the Philippines against the will of the population and then working to “civilize them” when there was still so much discrimination against African Americans at home.

Using primary sources such as this declaration from the Colored Citizens of Boston protesting the Filippino War, or “The Black Man’s Burden,” a response to Rudyard Kipling’s famous poem, “White Man’s Burden,” help provide alternative perspectives. Furthermore, the anti-imperialist view of the Colored Citizens of Boston is echoed in all the subsequent wars of the 20th century. I use this YouTube clip (starting at minute 1:51) of Muhammed Ali’s stance on Vietnam to demonstrate the parallel.

So whatever units or periods of American history that you teach, do some research. (See resources below for places to start.) You will find something on the role Blacks played that can fuel discussion and illuminate greater truths about the period. Whether it is the opportunities of the workers in the Gilded Age, or the cowboys out west, or the suffragists fighting for women’s right to vote, or the impact of World War II – there are Black people involved.

Reason 3: Our nation’s present problems with race and intolerance make no sense if we don’t know the history behind it.

As I write this post, the New York Times has just published The 1619 Project which examines “the ways the legacy of slavery continues to shape our country.” The last several years have brought renewed attention to the impact of slavery on the world today. (See the excellent podcast, Seeing White, from Scene on Radio.)

Whether you are looking at today’s rise of white supremacy movements, contemporary efforts to take down Confederate monuments, or the advantages slavery had for Northern institutions, it is clear that slavery was the major plot line of American history in the past and continues to inform the present.

When we teach Black history in isolation – as a pause for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., or a few heroes in February, or worse, as a few days spent on slavery, its abolition in 1865 and then nothing until Brown v. Board in 1954 – we contribute to our nation’s amnesia about race.

Our students – even in all/mostly white communities – know that race is a major issue in our country. When we don’t acknowledge that, when we don’t teach about the roots of it, then the misunderstanding and the racism continue. As I mentioned in a recent post, Professor Steven Thurston Oliver speaks eloquently about this issue in a podcast for Teaching Tolerance’s Hard History: American Slavery.

Reason 4: Students like Black History

In my experience – no matter what the racial composition of a student is – they like African American history. They like it because it is about justice and injustice. And there is nothing like injustice to stir the passion of a 13-year-old.

Sharecroppers evicted 1936, John Vachon

During my unit on the Great Depression, I use an engaging, 10 minute film clip from the History Channel. I watch students watch it (and they are mostly watching), but I always have a few who drift in and out. Until the part when noted actor Ossie Davis comes on and talks about FDR’s fireside chats.

Davis says, “…and me, a little Black boy down in Georgia…it wasn’t that [FDR] told it to Daddy…or told it to Mama. No, he was talking to little Ossie.” And when he says that, I kid you not, the entire class, including the white kids, perk up and refocus. I know, because I have watched all 5 of my classes for the past few years I have shown this, and it never fails. The same thing happens every time. There is something about that comment (and it’s not just Davis’s wonderful voice) that speaks to them.

This is how it is whenever I teach Black history. Middle school students are (please forgive my broad generalization here) idealistic, full of hatred against anything that isn’t fair. Too often they feel powerless. African American history is all about that and more.

3 Important Caveats

Remember that there is diversity of experience over time and place. Do not treat all African Americans alike. Not every Black person was a slave. Slavery was different in the North from the South. Consider urban vs. rural, small farm or large plantation. Consider the conditions of Black people in the colonial period vs. antebellum vs. 1920s.

The Great Migration fundamentally changed the demographics of our country and life was different for those who made the journey and those who didn’t, for those who followed family and for those who were the first to arrive. There is a beautiful expression of this by classroom teacher Jordan Lanfair in #15 of the Teaching Hard History: American Slavery podcasts at about minute 38:00.

Even African Americans who had the same experiences did not interpret them the same way. I love to use two opposing documents about women’s suffrage from Booker T. Washington and Du Bois to illuminate this. Students are surprised that a Black man would oppose women’s suffrage.

Be sure your entire focus is not slavery and oppression. It shouldn’t be, and not only for the sake of our Black students, who can be justifiably proud of the enormous impact Black culture continues to have on everything American. While slavery and oppression, of course, are a major part of the story, they don’t explain the cultural longevity and successes of African Americans, nor their unique contributions to the arts, to literature (including SF), to music, to sports, to business, to science and mathematics.

One source I especially like to use to address this is a brief video from a New York Times interactive collection featuring the voices of “hypenated” Americans. Michaela, a very light-skinned woman who identifies as Black, is so proud of her identity she pointedly asks, “Why would I want to be White?”

Another piece of cultural history is found in a chapter from Langston Hughes’s 1940 autobiography, The Big Sea, called “When the Negro Was in Vogue.” Students will see echoes of the role African American culture played in the 1920s in our society today.

And one last question you might have….

So if you do this all year, what do you do in February? I’m still wrestling with this question. It is probably wise at the start of the month to explain to students the story of how Black History Month came to be. History.com’s video does this well. I then remind them of other designated months.

You might consider a discussion of what African American history month is for. Is it a celebration of famous people and contributions? A time to focus our attention on the history of African Americans as a people? Is it a time to focus on the successes and the victories? Or the struggle? Or the work yet to be done?

To do all this well, you will need sources other than a textbook. A few of my favorites are linked below.

Resources

- Ta-Nehisi Coates’s “The Case for Reparations” is an important article that is really an overview of the impact of slavery. I also like the essay by Lonnie Bunch, the director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, about the continuing importance of Black History Month.

- Teaching Hard History: American Slavery – from Teaching Tolerance

- Stanford History Education Group – great lessons that need editing for middle schoolers.

- Race in U.S. History – from Facing History

- The 1619 Project Curriculum

- The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture – part of New York public library

- National Museum of African American History and Culture

- The DuSable Museum of African American History

- Guidelines for Teaching about the Holocaust – useful for pedagogical issues to consider when thinking about painful topics, like slavery, Jim Crow and lynching.

- The Top 8 Mistakes Teachers Make When Teaching the Modern Civil Rights Era And a Few Suggestions on How to Fix Them

Thank you for this article. It articulates perfectly all the ideas I have about how to teach history in an inclusive way. Though I appreciate the purpose of Black History month, it does tend to allow teachers to avoid the importance of African Americans in ALL parts of our history.

Thank you. I think Black History month is still important and needed, but I agree–it can also lead to ignoring this history until then.

How sad that so many of the ideas here are so racially divisive – just after 2 successful elections of the first black president. What part of the American dream are citizens not allowed to partake? Yes, MLK lived at a time when Jim Crow was still highly active– and his speech was a catalyst for freedoms enjoyed now. Even then he said, “Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.” Yet, the recommended video of Muhammed Ali, refusing to fight when called by his country (many did this) has him yelling “you white people are my enemy!”

And “there’s nothing like injustice to stir a 13-year old!” It just seems your recommended curriculum seems to be grievance based. Which seems antithetical to MLK’s vision of a color blind world. Does it imply that “whites” have an idyllic world without problems? To actually be fair, we have to teach Hispanic history, Asian history, LGBT history, Filipino history, and so forth. As we break (and keep) individuals in their respective groups, we totally lose the idea of “American History.”

I can see why so many Americans hate the country and deny anything good about it. We need to see people as individuals – not divided into grievance/victim groups. Does your curriculum strengthen or weaken that?

I don’t see my suggestions as grievance-based; I see them as U.S. history. Muhammed Ali was speaking at a time when there was significant racism impacting Black Americans. And, as I mentioned, I used the clip during a lesson on the war with the Filipinos. It illustrates a recurring theme in American history. It does not imply that other groups do not have problems.

The quotation you mention from MLK about not drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred is a poignant one; and speaks to the broad point you are making. We do, I agree, have to be careful to avoid presenting a view of American history that is so depressing our students lose hope. While I say that there is nothing like injustice to stir a 13-year old, the corollary is that they have tremendous hope and idealism, and we must do all we can to harness that.

That is why I think teaching about past injustices is so important; many of these injustices have been addressed. But King’s “vision of a color blind world” is a vision that I do not think has yet been achieved. We are not in the “post-racial” world that many spoke about following Obama’s election. African Americans still fall behind Whites in so many areas– education, economics, health. The evidence is quite clear. Being “color conscious” in the classroom means being aware of and sensitive to the many different backgrounds and cultural roots of our students. That awareness is necessary to teach effectively. Color-blindness, in that context, would not be acceptable. Nor would color-blindness in teaching about the past.

I believe in E Pluribus Unum; out of many, one. I do not think that telling the stories of different groups detracts from the story of our nation as a whole. It’s not all about grievances and victims. It is also about overcoming adversity and adding to the body politic. I just finished listening to the first podcast of the 1619 Project: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/23/podcasts/1619-slavery-anniversary.html There’s a lovely bit at the very end (about minute 36:00) where Nikole Hannah-Jones explains the role African Americans played in fulfilling the promises and ideals made by the Declaration of Independence and the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments. It’s a beautiful thought about the ideals for which this country stands.

I would just like to say as an African American student, I’m glad that you took the time to actually try to teach and educate people as to why it’s important to teach African American history – which is in fact American history. Thank you so much for making an effort.

Hello Ms. Brown.

I teach African American Studies in a small town in Southern Oregon. This is the second year I have used your blog to inspire my students. I think your piece gives us the “why” and purpose to our semester-long course.

I love your voice. Many of my students appreciate your perspective. It gives them a base from which to start our 2nd semester which covers Jim Crow through Civil Rights. I am grateful to have this blog to hand out to my students, and I thank you.

Although I have taught African American studies twenty years ago, in an urban high school in Portland, Oregon, I moved down to this rural area in 2008 and finally had the chance to push our school Board to adopt the class that I am teaching now: African American Studies is now a way students can receive US History credit.

I would love to stay in touch and share ideas if you are up for it. Again, you are one of our heroes in my class, Ms. Brown. Thank you for your wonderful blog.

How about teaching kids all the cool things black people invented? Automatic transmissions, refrigeration, blood transfusions, elevators, etc… with all the focus on the bad people forget all the good things. I feel like if everyone could address the obvious, like slavery, and include all the things we use today that were invented by blacks it might brings us together as a nation…..just saying

@Kellen, I’m sorry I’m only just seeing this. Thank you so much for your comment. I followed you on LinkedIn and Twitter. If you do the same, I can DM you. I would love to connect.

@Pedro Just saying back at you–a great idea. I’m not optimistic that this will bring us together as a nation, but I agree that we need to focus on the many positive accomplishments. I didn’t know about elevators!