Learning How to Teach Controversial Topics

A MiddleWeb Blog

So what happened?

Last year, my partner eighth-grade English teacher and I co-assigned Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give for summer reading. We thought it would be a slam dunk: high interest, hard to put down, much acclaimed, relevant to current issues.

The book has won a slew of honors, including the William C. Morris YA Debut Award, the Coretta Scott King Book Award and the Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature.

In addition, the novel tied into themes shared across our English and U.S. history courses, of being an upstander and telling our stories. It also connected to one of our essential questions, inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates: What does it mean to be a “conscious citizen of this terrible and beautiful world”?

Depth of Discussion

And in our class discussions we did experience many moments of connection and richness, even goose bumps.

In English, the eighth graders tackled code-switching, Tupac’s poetry, the impact of a strong African-American female narrator.

In history, we talked about Emmett Till’s death as a catalyst for the civil rights movement, as described by his mother. We read Junauda Petrus’ essay, “Can We Please Give the Police Departments to the Grandmothers?” from Maureen Johnson’s How I Resist: Activism and Hope for a New Generation. In response, students made their own list of songs inspired by Petrus’ writing, using these directions.

The range of topics we were able to consider – from literary, cultural, social, racial and historical perspectives – was vast.

The Power of Empathy

With the depth of such conversations and connections also came discomfort.

What we didn’t anticipate was that simply assigning this book would end up feeling like a political act. As Jennifer Gonzalez sagely asked on Cult of Pedagogy for a book study in 2017,

“I wonder how teachers might address concerns from students and families who see the book as biased, or who feel more sympathetic to officer one-fifteen? Some students (and teachers) may relate more to characters like Hailey … how do we address this in our classrooms in a way that helps everyone grow?”

What became clear as we discussed the text is that the book is so incredibly well written – it was, in fact, the master text for an online UCLA class I took last year on writing a young adult novel – that it can be hard to imagine the officer’s point of view. And we did listen to students who wanted to tell a different story, one that salutes the bravery of the police officers they know and love in their lives.

Rethinking for Next Time

So what lessons would I take from the experience the next time I teach this book, or what would I tell our ninth-grade English teachers who are thinking of teaching it in the future?

Here’s what worked well:

1. We used the book as a springboard for all sorts of related discussions, with themes that would arise all year in the literature and current events we discussed.

2. We responded to what we were hearing from students. After a few days of stilted conversations in which students weren’t necessarily understanding each other’s perspectives, I knew we had to do something different than what I’d planned, an extensive look at the civil rights movement.

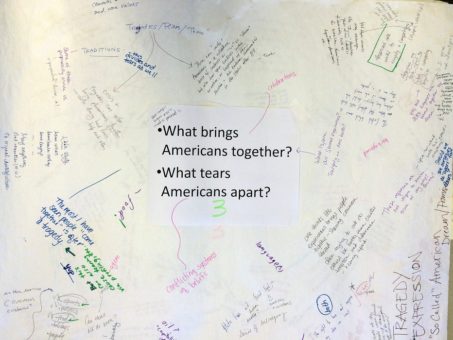

Instead, I drew upon one of my favorite strategies for processing difficult topics, silent graffiti, and asked why people might find it difficult to talk about controversial issues such as Black Lives Matter. As Facing History and Ourselves notes, this kind of quiet written conversation can be an especially effective approach “when you want to avoid analytical or intellectual discussions and allow students to process emotion.”

3. We did freewrites when helpful. For ten minutes, I would ask students to write on what it might mean to be a catalyst in terms of history, or how they felt about a certain topic. Often I would not even read these reflections, just provide space to air private thoughts.

4. We got real very quickly. Between this book and a current events spoken word poetry project I’ve started with for several years, I glimpsed students’ passions and opinions early on, knowledge that helped us transition into deeper discussions about history and the news.

Here’s what I might do differently:

1. Teach the novel later in the year. This book was a fabulous summer read in that students couldn’t put it down, but it was a difficult summer read in that their English and history teachers weren’t around to give context and answer questions while they were reading.

2. Send a letter. We actually wrote a letter to parents but didn’t send it, because we didn’t want to stir the pot unnecessarily. In retrospect, it would have helped to give parents a window into our thoughts with paragraphs such as this:

“For history, The Hate U Give braids beautifully into two strands of our curriculum. First, it tackles a current controversial issue in a way that builds empathy. In eighth-grade U.S. history, we discuss current events just about every day, and we are always trying, as Atticus Finch says, ‘to climb into someone’s skin and walk around in it.’ Students will work to build empathy themselves with the first project we do, a spoken word poem on current events. Second, the novel connects thematically with multiple content areas in our curriculum, including the Civil War and the civil rights movement, as well as with To Kill a Mockingbird in English.”

3. Highlight additional voices. Many of my students wondered about the perspective of police officers, such as Starr’s uncle Carlos, who walk the beat each day. We could explore articles such as this one on empathy in policing and even ask a law enforcement official to visit our class as a guest speaker.

Taking a Deep Breath and Looking Ahead

As this school year gets underway, I know we will face moments every week, if not every day, in which individual students express stunningly different views on hot-button issues.

Yet even as my missteps in teaching this novel hover in the background, I would also like to remember what worked beautifully and deepened our classroom culture: Bringing in supplemental sources. Giving students space to process the intensity of their classmates’ emotions. Leaning into the discomfort.

See the 2019 Nominees here and vote by Oct. 12, if you’re 12 – 18.

I also want to remember that we live in exciting times for writers and readers of young adult novels – and that, despite my abiding passion for primary sources and current events, sometimes the most visceral route to understanding arrives through important fiction that we should be teaching.

____________________________________________