New Schema: Standards Based Report Cards

A MiddleWeb Blog

I never met John Dewey. And despite my preservice teacher training, all those years ago, the story of his life and his impact on education were buried somewhere deep in the recesses of my aging mind.

I never met John Dewey. And despite my preservice teacher training, all those years ago, the story of his life and his impact on education were buried somewhere deep in the recesses of my aging mind.

His story was absolutely (very) prior knowledge; I just couldn’t seem to readily retrieve the specifics about any of his noted contributions to education.

Actually, my first cognitive thought was that he was the man who came up with the idea of organizing books by means of a decimal system. A brilliant idea, but not one of John Dewey’s. That was Melville Dewey, in 1876, about sixteen years after John was born.

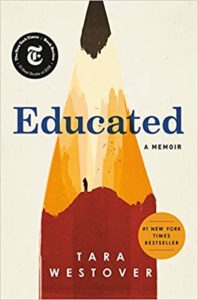

There was no reason for me to even think about John Dewey, or his impact on education, until my son was given a summer reading assignment to complete prior to beginning his freshman year in college. He was asked to read Educated, a memoir written by Tara Westover. I’d never heard of it, but I found the title intriguing.

Summer ended and Educated went off to school with my son. He wouldn’t let me keep the book at home. He said he might need it for future classwork and discussions. As a mother and a teacher, that made me proud.

The madness of a new school year and the launch of Standards-Based Report Cards in our district put any thought of Westover’s novel out of mind, but during a recent visit to campus, I saw it sitting on his dorm room desk. I scooped it up and tucked it under my arm. “I’m taking this now, my dear. If you need it, I’ll drive it back to you.”

“All good, Mom,” came the response.

The Father of Pragmatism

A few days later, John Dewey’s words looked up at me from the very first page of Westover’s novel. She’d chosen a quote from him to begin her story. It simply read, “I believe finally, that education must be conceived as a continuing reconstruction of experience; that the process and the goal of education are one and the same thing.”

Dewey’s definition gave me pause for thought. I’m curious by nature, so I researched his life a little further. I came to the conclusion that Dewey, the Father of Pragmatism, would most likely suggest I try to be pragmatic about all of the changes currently going on at school and to use my own unique experiences to reconstruct my current teaching practices.

Pragmatism is defined by Merriam-Webster as having “a practical approach to problems and affairs.” The recurring problem, the history that keeps repeating itself, is the challenge of figuring out how to offer the kids the freedom to learn from their own experiences in an environment that Dewey describes as “flexible enough to permit free play for individuality of experience and yet firm enough to give direction toward continuous development.” Dewey assures me that it’s the process itself that defines each of my learner’s own, personal education.

Right now, the process I am trying to untangle is how to streamline the use of Science and Social Studies units to support our development as readers, writers, and thinkers. We are scheduled to start our third ELA Unit of Study, the study of non-fiction.

I’m a little behind, according to the curriculum map, and I’m having a little difficulty finding time to complete all of the Investigations in our first Science unit, but we are making steady progress in our first “official” Social Studies unit, the Age of Discovery. Our Essential Question for the unit asks, “Why do people from diverse cultures sometimes experience conflict?”

It’s a good question. It’s a question we’ve been discussing on the read aloud rug on a daily basis. On the reading rug I try to weave Math, Social Studies and Science objectives into our workshop mentality. This seems to be the only way to achieve many of our district’s educational goals across multiple disciples of study in the actual time we have to teach.

Using the district’s Social Studies and Science curricula in our next reading and writing units is an idea worth trying. We can explore text features and text structures while learning about early exploration and colonization. We can connect current advances in science to the great minds that came before them.

A new schema: standards-based report cards

I have twenty-six folders full of student artifacts that will give me insights to use with this year’s new, standards-based reporting system. As I gather individual artifacts and place them in ever-expanding student folders, I peruse the possibilities of how to approach my first round of Standards-Based Report Cards.

After over twenty years of inputting grades, calculating percentages, and using the narrative portion of the assessments to give authentic feedback, this experience inherently represents some big changes in perspective and my long-established grading schema.

I need to remind myself that this is the first year in developing my Standards-Based-Report-Card schema. My student folders hold all the primary documents I’ll need: a wide variety of reading and writing responses, a slew of Pre- and Post-Assessments, Quick Writes, Claim-Evidence-Reasoning responses to inquiries, and Post-it Notes written in response to our class read alouds.

All of these pieces of evidence offer me a look at each child’s comprehension skills, expressive writing, sentence mechanics and language awareness. These cross-curricular artifacts hold part of the answer to my streamlining problem. And next year, I’ll have the coming weeks to look back on and a fresh report card schema to use.

Dewey believed Education was the process and the goal, that we are continuously becoming educated. He was onto something. I need to relax and trust the process.

Last week, I received an email from my son. He attached the paper he’d written about his summer reading assignment, Westover’s Educated. In his opening paragraph, he responded to her story with a claim that, “Curiosity is one of the many key components that led humanity to the point it is at today.”

Curiosity as a luxury? That’s an uncomfortable idea.

I’ve only had time to read a few chapters of Westover’s Educated, but I’ve already made some text-to-world connections. Westover and Melville Dewey both began their earliest education as members of deeply religious families. Melville was raised in what’s known as a Burned-over area of rural New York State, and Westover acknowledges her parents’ well-intentioned but radical beliefs and their effect on her earliest education as she grew up in the mountains of Idaho. As far as plot structure goes, I’m already hooked.

Finding the time to finish exploring the view from Westover’s mountain is certain to give me some more uncomfortable and uncharted perspective to work with, as my own reconstructed version of education continues to be refined.

For now, I will do my best to be a curious pragmatist, attempting to crisscross curriculum content while collecting student artifacts. I’m going to need to remind myself of John Dewey’s words. If I’m being a pragmatist, I will view the process as the goal of my own, individualized education.