How iCivics Helped Me Refresh the Constitution

A MiddleWeb Blog

In my 8th grade U.S. history and civics class, which I’ve taught for seven years, our unit on the Constitution has always challenged me because it raises so many questions about curriculum planning:

♦ How do I balance talking about the Constitutional Convention with our discussion of the Constitution itself?

♦ How many primary sources should I sprinkle in? Is it worth it to take time to browse through some of James Madison’s notes from the Convention, or would that time be better spent analyzing the lasting impact of the Great Compromise?

♦ If we read all of Articles 1, 2 and 3, rather than a summary of each branch’s power, do basic understandings of checks and balances get lost?

Ultimately, on a small scale, this Constitution unit replicates the conflict between breadth and depth that we face as social studies teachers every day.

This year I decided to get help in the form of lesson plans from iCivics. In the past I’ve used iCivics games and DBQuests for supplemental activities, but as a member of the iCivics Educator Network I knew the site also had a trove of readings and handouts I had barely explored.

The Big Hits of the iCivics Curriculum

To find iCivics lesson plans on the Constitution, I simply went to the Teachers section and selected the curriculum units tagged the Road to the Constitution and the Constitution. At the same time, I was also beta testing a cool new civics search program called Composer, which led me to some of the same lesson plans.

How did it go? A whole lot worked well:

1. The readings are visually appealing and straightforward. Compared with a regular textbook, iCivics has more graphical interfaces and fun pictures, not to mention readable and lively text. When I hand out an iCivics reading, kids don’t groan, as they sometimes do with heavier-looking assignments.

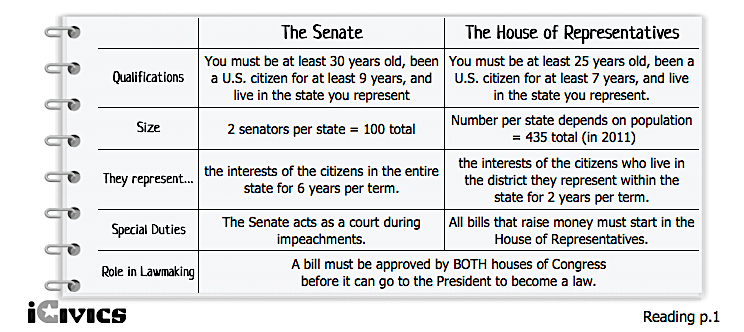

For instance, Anatomy of the Constitution has some of the clearest charts I’ve seen on the House versus the Senate. Hey, King, Get Off Our Backs! features entertaining thought bubbles from the likes of Patrick Henry and King George III, and No Bill of Rights, No Deal includes an appealing one-page version of the first ten amendments. (You’ll need a free teacher account to access some of this content.)

2. The activities accompanying each reading are varied and require different levels of thinking, challenging a range of students while also giving “brain breaks.”

The lessons offer activities to prepare kids for reading a difficult document, primary source snippets embedded within worksheets, exit tickets to assess understanding, PowerPoints to accompany each set of lessons, and much more.

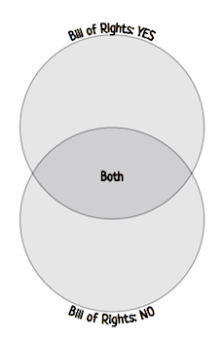

Within the handouts, I enjoy the combination of rigor and playfulness. In No Bill of Rights, No Deal, a Venn diagram showing overlap between “yes” and “no” views of the Bill of Rights required students to talk through every argument to make sure they truly understood it. By the time they finished, they were conversant with the Federalist and Anti-Federalist positions in a way I hadn’t seen before.

Later in that same packet, primary source excerpts were also difficult enough that students gravitated toward each other for discussion. And one of the last activities, a brief crossword on the 9th and 10th Amendments, asked for less focused brain power but still taught key vocabulary.

3. The authors of the curriculum show good judgment about appropriate level of detail and relative importance of facts.

As a history teacher, I often chafe against the depth of information in textbooks intended for eighth graders. It’s sometimes too little or, more often, too much. Do we really need to know every bit of every event from 1763 to 1775 that led to independence?

iCivics lessons tend to lean toward the side of simplicity, but without sacrificing important content and ideas. For instance, the Colonial Influences lesson begins with student-generated definitions of five key terms – rule of law, self-government, due process, limited government and rights – that appeared in documents such as the Magna Carta in 1215, the English Bill of Rights in 1689, and Common Sense in 1776.

The lesson’s reading gives a paragraph about each of these three documents, plus the Mayflower Compact from 1620 and Cato’s Letters from the 1720s, to show philosophical influences on the Constitution – short and sweet but effective.

4. The games!

Enough said. iCivics games, while they won’t compete with whatever is happening at home on the Xbox or PlayStation, are compelling enough to keep kids playing and figuring out their concepts. My students have especially enjoyed Do I Have a Right?, Branches of Power, Immigration Nation, and Power Play – and there are many more we have yet to explore together.

Adding My Own Sparkle to Make the Curriculum Feel Even Richer

On the days we did readings and then handouts, I found myself conflicted. My students were talking through concepts together. They were learning. But I didn’t feel I was doing much as a teacher because the plans were so self-directed and paper-based, and I wanted to add a little pizzazz.

Additions that tossed in some of the “sparkle” I was hoping for included:

► Showing brief videos on the Bill of Rights from Constitution USA and how a bill becomes a law from Schoolhouse Rock, eternally classic. (Jack Sheldon, the voice of “Bill,” just passed away.)

► Projecting a photo of the Supreme Court and discussing the gender and racial composition of the current justices; searching up portraits of the Founders and then comparing them to a photo of the cast of Hamilton: A Musical; finding a picture of Thomas Jefferson’s library as replicated in the Library of Congress.

► Tying in daily current events on the Constitution to the topics we were studying – for instance, a piece on the electoral college from Vox and a preview of the Supreme Court’s docket from the LA Times. Teachers can easily find a Constitution-related news article for every day of the year.

► Bringing in the occasional additional primary and secondary sources, such as a few pages describing the Founders’ five major achievements and two “shadows” from the prologue to Joseph Ellis’ American Creation (open the sample).

Wait Till Next Year

Overall, strengthening my Constitution unit with iCivics readings, activities and handouts was a success. I felt that my students had a better understanding of key elements of the Constitution, especially branches of power and the Bill of Rights, culminating in a concept map connecting the unit’s ideas.

Next year, I would probably supplement even more with videos, photos, primary sources, secondary sources and current events to make our national set of laws feel even more like a living document.

However, I think I will have to accept that, no matter how carefully I plan, I will never feel satisfied, never feel I’ve taught everything that’s important about the Constitution – perhaps, like the Founders themselves, always striving for a “more perfect Union.”