Our Students Need a New Definition of Writing

I identified as a writer early on in life, spending my afternoons reading books like Beverly Cleary’s Beezus and Ramona (1955) and Henry and the Clubhouse (1962) and attempting to write my own chapter books about gangly, endearing boys and girls who – try as they might – cannot help but get into trouble with meddling grown-ups.

Later on, I earnestly filled notebook and computer paper with short horror stories and wry commentaries in the style of Stephen King, Dave Barry, and Erma Bombeck.

My teachers and other adults said I had an unarticulated and vague “talent” for writing that closely matched the kind of writing most privileged in school spaces – personal essays and literary analyses and (largely) feeble attempts at creative fiction. I say all this not to brag, but to be transparent about the positionality I take when speaking or writing about…well, about writing.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that my schooling experiences contributed to a severely limited view of what “writing” was. The vast majority of the writing that I read in school as well as that which I composed was alphabetic. I rarely had the opportunity to compose visually, aurally, or multimodally.

Outside of school spaces, my reading life was much more broad and included such multimodal and visually heavy texts as Mad magazine, Archie comics, and popular feminist zines of the 1990s. Even so, it seldom crossed my mind to consider these forms as writing. It wasn’t until my late 30s and early 40s that I realized these alternative modes and forms of composition – comics, infographics, photo essays, etc. – could offer me the kind of joy and rigor that I had felt throughout my childhood while composing in more “dominant” forms.

However, even throughout my graduate school years (which began approximately twenty years ago and have continued on and off ever since), I have only been afforded the choice to compose using something other than the exclusively alphabetic mode a handful of times.

These moments while occupying school spaces have been so few and far between that I can name them here: the digital poem remix (posted here), the annotated bibliography (which included photos of book covers), the illustrated book of original poetry. Even then, I wasn’t taught how to write these forms of composition, but was merely assigned them for various classes. Everything I know about composing in modes other than that which relies almost exclusively on words to convey meaning has been largely self-taught.

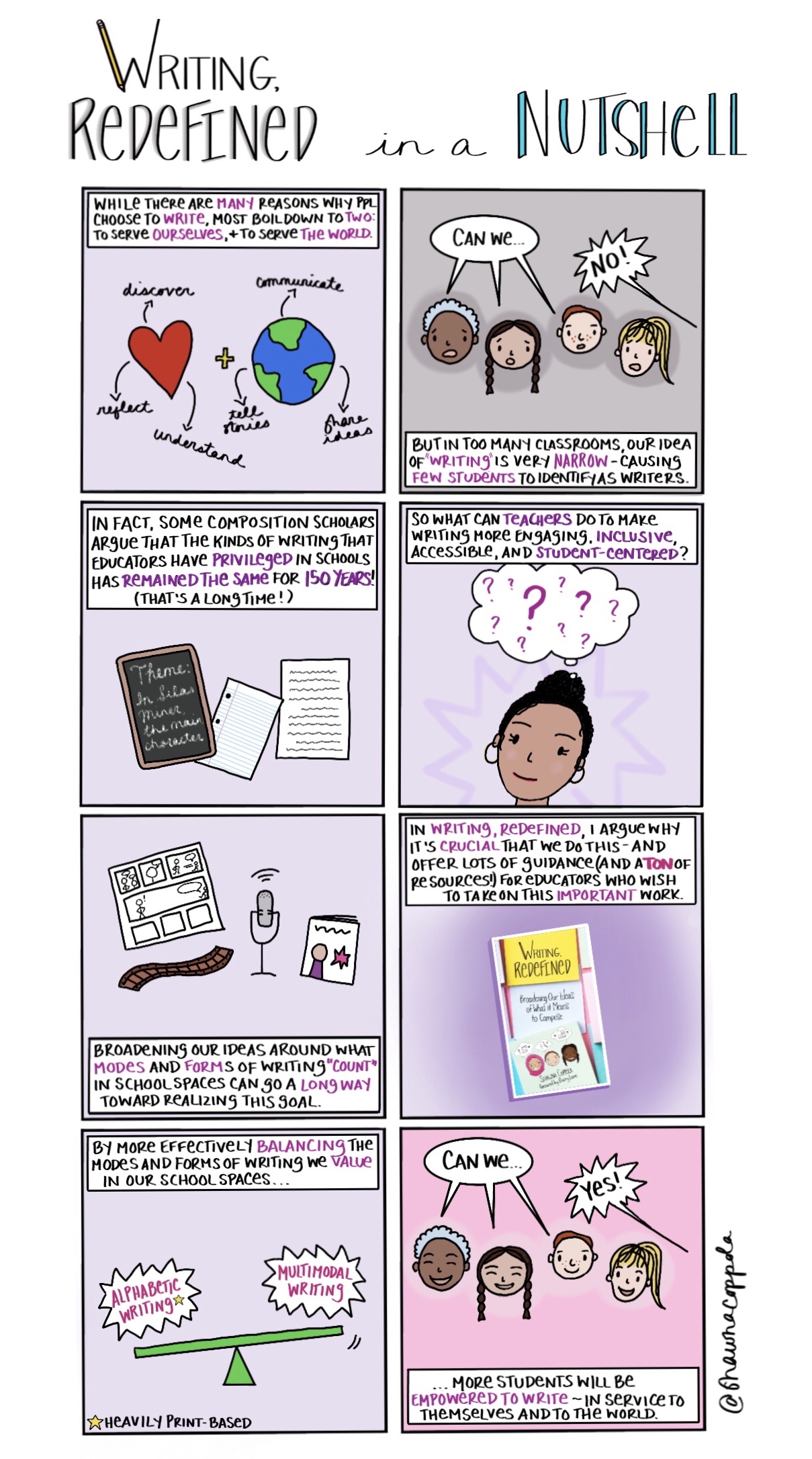

Broadening Our Ideas about “Writing”

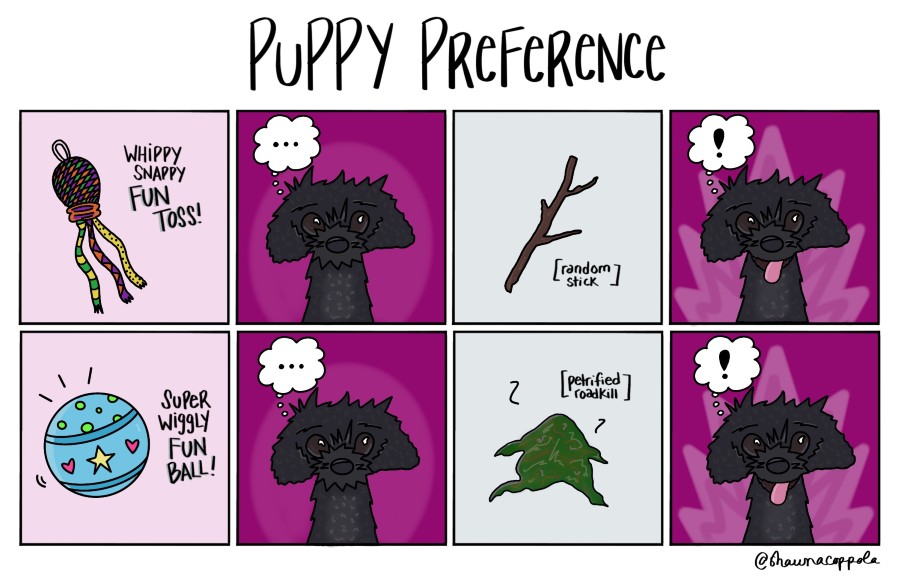

When we think about the kinds of students who typically identify (or who educators identify) as writers, whom do we think of? In my twenty years of teaching and coaching, this group, this “writing club,” has felt far too exclusive. Several years ago as my repertoire of composition broadened far beyond by my youthful conceptions, I began to wonder what would happen when educators began to consider “writing” more broadly.

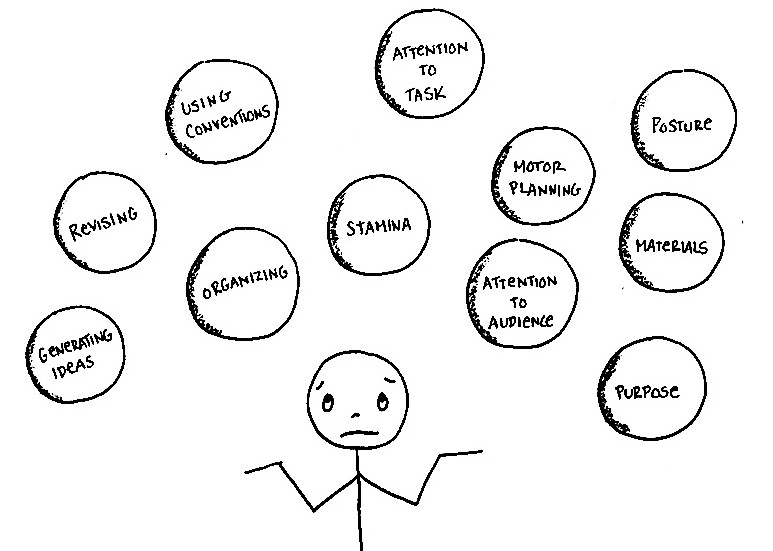

After all, if we think about the kinds of decisions we make as writers, we make almost all of the same kinds of decisions – about audience, content, organization, craft, even motor planning – whether we are composing a typical personal essay or a wordless picture book.

The mode, the materials, and the kind of text (e.g., alphabetic, visual, etc.) we use to convey meaning may differ, but we are still composing. We are still “writing.” Unfortunately, the stories educators tell about what writing “is,” and about what kinds of writing are most privileged in school spaces, do not reflect this reality.

This reality also actively disengages youth who simply prefer to compose using forms that incorporate visual, aural, and multimodal texts as a way to make or enhance meaning – forms such as podcasts, zines, and others I’ve already mentioned.

Just because educators have traditionally served as gatekeepers of the kinds of writing that “count” or are privileged in school spaces doesn’t mean we can’t also actively work to change this – thus making writing more inclusive, more engaging, and more likely to reflect the larger world outside of school.

“Redefining Writing” in Practice

In my book Writing, Redefined I offer practitioners a wide variety of ways to subvert the dominant narrative of what writing “is” in school spaces. These include incorporating visual, aural, and multimodal modes of composition in our practice in ways that will not only enhance more dominant modes and forms of writing, but are meaningful and engaging ends in themselves.

In addition, I explore the age-old concept of “remixing” – of taking existing content, such as a book review or a piece of poetry, and playing around with form, genre, and mode in order to create something entirely new.

For example, in Chapter 2, “Writing Is…Visual Composition,” I explain how composing something with visual text, such as a wordless picture book, is just as complex and demanding (if not more so!) as composing something using exclusively alphabetic text, such as a short fiction story.

I then compare it to existing writing standards to demonstrate its complexity. Throughout the book are woven both student and non-student examples of mentors that folks might use as they engage in this work with children and youth.

The truth is, if we take inventory of the forms and mode(s) of writing we assign and teach in school spaces – including those I assigned and taught my first few years as a classroom teacher – and compare it with the much wider array of forms and modes of writing that children and youth are engaged with outside of school spaces, we will quickly realize unintended consequences.

Instead of opening the doorway to a much larger set of students to identify as writers in a general sense, our instructional practices are narrowing the definition with every passing grade level, while we are simultaneously shutting out many who possess incredible gifts for storytelling, for persuading an audience, and for sharing their own important lived experiences.

Over fifty years ago, in their book Teaching as a Subversive Activity (1969), Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner echoed the words of American sociologist David Riesman when they argued for a broader definition of literacy due to the fact that “print no longer ‘monopolizes man’s symbolic environment’” (165).

As we head into the third decade of the 21st century, this sentiment is as undeniable as ever. It’s past time to ensure that our practices around writing instruction reflect this reality – for our students’ sake as well as our own.

References

Coppola, Shawna. 2015. “Digital Poem: Georgia Heard’s ‘Straight Line’.” My So-Called Literacy Life (blog). https://shawnacoppola.wordpress.com/2015/03/24/digital-poem-straight-line/

Coppola, Shawna. 2017. Renew! Become a Better – and More Authentic – Writing Teacher. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Postman, Neil & Charles Weingartner. 1969. Teaching as a Subversive Activity. New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

Shawna is also the author of RENEW! Become a Better – and More Authentic – Writing Teacher (2017). Shawna’s latest book, Literacy for All: A Framework for Anti-Oppressive Teaching (Routledge, 2024) is reviewed here at MiddleWeb. Visit her website.