Watch Out for Unintended Microaggressions

A MiddleWeb Blog

Topic ideas for my blog posts usually arise organically from what is going on in my school life at the time. This past month, a confluence of events led me toward the topic of microaggressions that teachers may unknowingly commit involving their students.

Topic ideas for my blog posts usually arise organically from what is going on in my school life at the time. This past month, a confluence of events led me toward the topic of microaggressions that teachers may unknowingly commit involving their students.

A couple weeks ago during our memoir unit, I was chatting with my students and was asking them to recount an important school memory. One of them said that fourth grade was okay but there was a class she didn’t like. I asked her why and she said it was mostly just the teacher.

She then gave a couple of examples of things this teacher did that made her uncomfortable. First, she told me it took the teacher three months to stop calling her by another student’s name (never mind that one of the girls is Chinese American and one is Korean American). She went on to say that whenever they talked about “diversity” (the term the student used), the teacher called on a friend of hers to answer the question and her friend happened to be African American.

Other students chimed in with similar tales. This student could not articulate exactly why she was unhappy, but the things she described are what I mean by “microaggressions” and they lead to these kinds of feelings.

Jerry Craft’s New Kid: A winning graphic novel

At about the same time, I watched the results of the 2020 Youth Media Awards. I was thrilled to see Jerry Craft win the Newbery Medal for New Kid. This was the first time a graphic novel has won the Newbery – a groundbreaking event and cause for celebration among those of us who are graphic novel enthusiasts.

Another reason I was so happy is because this is an important book. I was lucky enough to receive an advance reader’s copy from the publisher during the 2018 NCTE conference. It centers on the story of Jordan, an African American student who enrolls in a prestigious private school where he is one of the few students of color.

New Kid link

When I read the book, I was struck by how seamlessly Craft wove the microaggression experiences of students of color (and even students who are different for other reasons) throughout the story.

From a teacher repeatedly mixing up the names of the black boys in the grade, to a white father telling his son to lock the doors when they came to pick up Jordan at his house, to a patronizing librarian recommending grim urban stories full of hopelessness to black students because they would relate to the protagonist regardless of their background.

There are many more examples on nearly every page, and they go beyond just things that happen to Jordan. Craft showed how Jordan felt about these incidents and how he struggled to find a place where he fit in in the gap between his neighborhood and childhood friends and his new school with its wealthy students. It deserved the Newbery, and I believe it is a must-read for all students and teachers. I have a few copies in my classroom library, and they are always checked out.

Becoming an anti-racist educator

For the last several years, I have been doing the work to educate myself on how to go beyond just being an ally to my friends, colleagues, and students of color and becoming a truly anti-racist educator. I know it is not the responsibility of people of color to educate me about these issues—I need to put in the time to learn about them myself.

Most recently, I read the wonderful This Book Is Antiracist: 20 Lessons on How to Wake Up, Take Action, and Do the Work by Tiffany Jewell. It is a book written for young people, and it helps them learn about their own social identity, the history of racism, and how they can use their anti-racist lens to move the world toward equity and liberation.

I followed up with the How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi. Even though I was familiar with much of the information in the book, there were still chapters that covered territory that was new to me. I learned a lot and the lessons will stay with me. I am looking forward to reading Stamped: Racist, Antiracism, and You by Kendi and award-winning author Jason Reynolds when it comes out next month.

Confronting one’s own biases

This work is tough, because it is difficult and uncomfortable to confront one’s own biases and learn how to be an antiracist. In the words of Maya Angelou, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.” I am still a work in progress, but I wanted to share some of what I’ve learned.

It is a wonderful book I highly recommend to students and adults alike. One sentence contained a message that really stood out to me, “You have a right to be seen and understood without having to compromise who you are” (page 13). This is a beautiful message and is exactly how I want every child in my class to feel.

Recognizing microaggressions

I first became aware of the concept of microaggressions about ten years ago in a Psychology Today article by Dr. Derald Wing Sue. In it he states, “Racial microaggressions are the brief and everyday slights, insults, indignities and denigrating messages sent to people of color by well-intentioned white people who are unaware of the hidden messages being communicated.”

This is why I don’t assume any ill intent by the adults who commit microaggressions. They just may not know that what they are doing is causing harm to their students. (This does not, however, excuse this behavior. This information is out there for us and we need to do our homework.) Dr. Sue’s research and writing show how these racial microaggressions harm the target’s health.

Former students and a former professor at The University of Denver Center for Multicultural Excellence wrote a paper called “MicroAggressions in the Classroom” — based in part on the work of Dr. Derald Wing Sue. In it, they share some examples of common racial microaggressions (often unknowingly) perpetuated by teaching in the classroom. I’ve added my own comments for illustrative purposes.

1. Mispronouncing the names of students, even after they’ve been corrected. I have written before about just how important a student’s name is to their identity. It is just simple respect to learn their names and pronounce them how they wish. Along the same lines is calling them the name of another student of the same racial or ethnic background and/or saying their name is too difficult to pronounce.

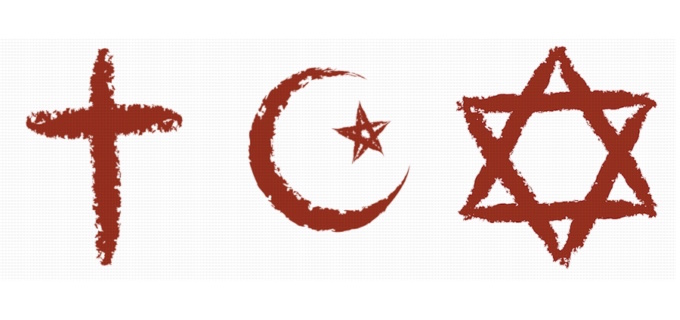

2. Scheduling assessment or projects on major holidays and the day after major holidays of religions other than Christianity. If you would not administer the test the day of or day before or after Christmas, then it doesn’t belong on Eid, Lunar New Year, Diwali, or Yom Kippur (all of which have students who celebrate them at my school). If you are unaware of when these are, you can consult the interfaith calendar website to help you when planning assessments.

3. Setting lower or higher expectations of a student based on their race or ethnicity. I have heard adults say they were surprised that a Chinese American student does not do well in math or that an African American student is such a good writer or public speaker. (This is when my antiracist sensibilities kick in and we have a discussion about these things.)

4. Using inappropriate humor about a specific group.

5. Asking a student to speak for or represent their entire group. It is not their job to educate others on their experiences or answer for a set of individuals. They should not be tokenized, and you should not direct all of your attention to them when discussing sensitive topics.

6. Not allowing all students to express their voice equally in classroom discussions. Make sure you call on everyone equally and allow all to share their thoughts in various ways.

7. Providing representation of only a narrow group of famous or accomplished people or reducing acknowledgement of a group to one month or day a year of recognition.

8. Asking racist questions such as, “Where are you from?” or saying, “You don’t look . . .”

9. Getting defensive when corrected about any of the above.

An essential journey

I want to reiterate that I do not assume harmful intent if a teacher commits a microaggression. I have done some of these myself. I just think it is worth our time to self-reflect and educate ourselves on how to do better.

One great place to start is by taking the Educator Self-Reflection Tool developed by Sharla Serasanke Falodi or checking out any of the resources below. Also, if a child tells you that you have done something that has caused them emotional harm, believe them, apologize, and promise to try to do better.

I am by no means finished with my journey, and I still have a lot to learn, but as a white educator I must do right by all our students. I hope that I am doing better by knowing better.

Antiracism Toolbox

Links referenced above

https://otl.du.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/MicroAggressionsInClassroom-DUCME.pdf

https://www.indiebound.org/search/book?keys=author%3AJewell%2C%20Tiffany

https://www.lbyr.com/titles/jason-reynolds/stamped-racism-antiracism-and-you/9780316453707/

https://www.harpercollins.com/9780062691200/new-kid/

https://cleartheaireducation.wordpress.com/about-cleartheair/

Helpful links not referenced above

https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story

https://scenicregional.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Mirrors-Windows-and-Sliding-Glass-Doors.pdf

https://www.heinemann.com/products/e09970.aspx

https://www.theantiracisteducator.com

http://www.beacon.org/White-Fragility-P1346.aspx

https://www.beverlydanieltatum.com

https://centerracialjustice.org

https://www.teachingforchange.org/books/our-publications/beyond-heroes-and-holidays

https://diversebooks.org/?fbclid=IwAR2eo7IxTuM6aSqOmJn3olx6v4E3P4ghs7YUZqSyZVd2zgq1Fmxr7k2DLeo

Another great, new middle grade book that specifically mentions Microaggressions is More to the Story by Hena Khan. I highly recommend it as well.

Brilliant piece, Cheryl! And what a timely article! I am going to follow up with the resources you suggested. I struggle with the challenge of not doing even inadvertent harm to those who are different from me. I know my heart, but I want to make sure to communicate it effectively to others without throwing up unnecessary emotional blocks through microagressions.

I ask lots of “white people” where they’re from. I’ve been on the receiving end of that question my entire life. The words “microaggression” and “racism” never entered my mind. America is racist, but it’s also incredibly diverse. White people don’t all come from “Whiteland.” My family is half Romanian and half Hungarian (and from a part of Hungary that when my maternal grandfather lived there would sometimes be Austria and then Hungary on the same day). When I meet someone with a definite African accent, I don’t hesitate to ask what country they come from. Same with Caribbean accents, and so forth.

This is called being interested in people’s stories. Maybe when someone else does it the motivation is strictly racist, but I’m skeptical that there’s racism lurking behind quite as many things as the PC mindset claims. And I will not go through life hobbled by paranoia and fear. Neither should anyone. If we stop assuming the worst about other people and projecting motives onto their behaviors and words that could just as easily be interpreted positively or neutrally, racism won’t disappear in a puff of rhetoric, but we might find it just a little bit easier to communicate.

Well said, Michael! I do the same thing. I’ve had the privilege to travel quite a bit, and I always like to find out where people are from to establish common experiences. I agree we need to be cautious about not being so politically correct that we fail to open up to each other.

On the other hand, I don’t want to carelessly make a comment or do something cavalier that puts someone, particularly a student, on the defense. These conversations Cheryl posed are good to have. Awareness is the first step towards understanding. I concur that the best solution is to not project motives onto others while remaining sensitive to our tone and intent.

I don’t disagree and I’m aware that there are people for whom “Where are you from?” is code for a lot of rather offensive assumptions: 1) You’re clearly not a “real” American; 2) anyone who is a person of color, speaks a language other than English in my earshot, wears “foreign” clothes, etc., isn’t a real American; 3) I need to know where you’re “from” (even if you were born in the USA), so I can know which stereotypes and biases to apply and which box to put you in.

And so on.

These microaggressions are quite common for students of color to encounter from preschool to graduate school. There are teachers and professors who will treat and respond to African American students disrespectfully and will treat Caucasian students with the utmost of courtesy and respect. Often lower expectations and blatant disregard for sensitivity in treatment for students of color can be rampant.

It is quite rude of someone to ask “where are you from” immediately, the first question, when one hears an accent. It makes the individual feel like the outsider or other. They will be responding to this question their entire life which can be quite bothersome. There are so many immigrant populations in the United States. So, hearing an accent should come as no surprise.

There are times in class when the topic of slavery or achievement gap comes up and the Caucasian professor will look directly at the African American student which in some cases may be the only one in the class.

These slights and rudeness can occur anywhere – on the supermarket checkout line, the doctor’s office, and definitely in the classroom.