Children of Blood and Bone: Four Takeaways

Recently I read a line in a book by Buddhist nun Pema Chodron advising people to wake up to their present moment. It’s possible, she warns, to take a long walk and not once smell the wild roses perfuming the air.

As it happens, I know Pema Chodron’s monastery is in Nova Scotia, where there is an abundance of wild roses in the countryside. They’re not cloying or overly sweet – their scent falls like light, lifting and traveling with the salt breeze from the sea. Spending time there a few years ago with my family over the summer, riding bikes along the cliffs, I had never breathed air so pure with wild roses. Without that experience I never would have known what Pema was really talking about.

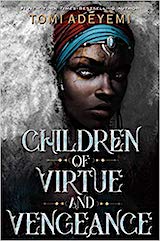

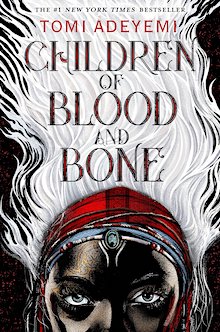

Reading Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone as a privileged white woman, I can only imagine that it evokes many meanings and memories, some deeply painful, that I can never fully experience “in the moment.” It strikes me that as I begin to learn how to talk about the YA books I am reading by People of Color, this is critical to acknowledge upfront.

It also means that I’ll be seeking from this point on not only to read more speculative fiction from POC authors, but also to temper and test all my views against POC reviewers’ thoughts on the same books. More to come on crystallizing that idea into action, but for now, please take a peek here at a thoughtful and thorough review of Children of Blood and Bone by Vann R. Newkirk II in The Atlantic magazine.

Four of my takeaways

In the meantime, here are four points that jumped out at me from this rich and necessary novel.

First, a brief summary for those unfamiliar with the premise: In a fictional land called Orïsha, populated entirely by people of color, the maji are a strata of society violently oppressed and literally disempowered by the lighter-skinned royal class. Three adolescent characters – a nascent maji magical warrior, and the son and daughter of the tyrannical king – take turns speaking in first person about their quest to return the power of magic to the maji, upending the current social order.

2. Adeyemi’s Author Note is critical. Read it first. Here the author does her readers the great service of offering a guide to her plot and characters that maps them directly onto the modern equivalents she sees in race relations in America.

She is at the height of these powers when describing the shattering inner experience of Zelie in Chapter 44, summed up in one sentence: “I will always be afraid.” This is the excerpt I would choose to close-read with a middle school class, pairing it with a journalistic account of the story of Philando Castile or Trayvon Martin.

3. Adeyemi’s narrative approach is unapologetically cinematic. She wrote the book in a style inspired by film adaptations with an eye towards production as a film, and this is abundantly clear in her pacing and plot. I don’t personally like this approach to book-based storytelling – if I want to see a predictable action film, I’m going to go to the movies. But it is a highly popular method of writing YA literature, it’s not going away, and it’s worth teaching as such to our kids.

Equipping our students with the tools to be able to analyze how plot and pacing choices are influenced by popular film is just one more way of helping kids consume their content critically, which is doubly necessary when it comes to themes of equity and inclusion.

4. The book contains explicit violence and sexual content. Your kids, families, and administration will need to be prepared for this in whatever way your professional expertise dictates is best for your teaching context. It might be easy to critique the level of violence in this book as unnecessary – in one chapter 538 people die, in overwhelming detail – before remembering the impact of the slave trade in African history.

If Adeyemi makes its violence shocking to us by concentrating its force into one blood-soaked scene, it is worth reflecting that estimates of human lives lost on the continent and in the Middle Passage number in the millions.