Conjuring Up an Almost Perfect History Lesson

A MiddleWeb Blog

Editors’ note: Educators’ lives have changed so much since Sarah sent this in late February. We know you may not see the inside of a classroom for months to come, but we figure there’s always space and time for a good tale of teaching serendipity.

Editors’ note: Educators’ lives have changed so much since Sarah sent this in late February. We know you may not see the inside of a classroom for months to come, but we figure there’s always space and time for a good tale of teaching serendipity.

During a recent week, I did two lessons with my eighth-grade U.S. history and civics students that afterward made me stand back and ask: Why did that work out so well?

Needless to say, I don’t usually have this reaction to my teaching – or my life. I almost always feel there’s something I could be doing better.

So I wanted to analyze why these lessons felt so rich: to imagine how fairy dust could billow once again if I pulled out these moves another time.

Lesson 1 – Layering Lots of Sources

The first 77-minute block period lesson pulled together pretty much all of my favorite kinds of sources – two secondary non-textbook readings, a newspaper article, a video and a primary document.

We were in the second week of a thematic three-week unit on women’s history, focusing on the journey to get the vote from the mid-1800s to 1920. The unit models an investigation into how social reform works, leading up to a major reformers research project.

Part 1 of our class time involved looking at homework assignments from the past two nights: a reading from TCI’s History Alive! Pursuing American Ideals and a chapter from Howard Zinn’s A Young People’s History of the United States. Both excerpts covered women’s history, first in the mid-19th century and then from colonial times to the mid-19th century.

After I mentioned that the Zinn reading is popular but can be controversial for its liberal slant, students paired up to list two differences or similarities between the readings. To many, the Zinn reading felt more like a story and came across as happily opinionated. On the other hand, some liked the textbook approach best because they felt it covered more facts – events, people, terms they could latch onto.

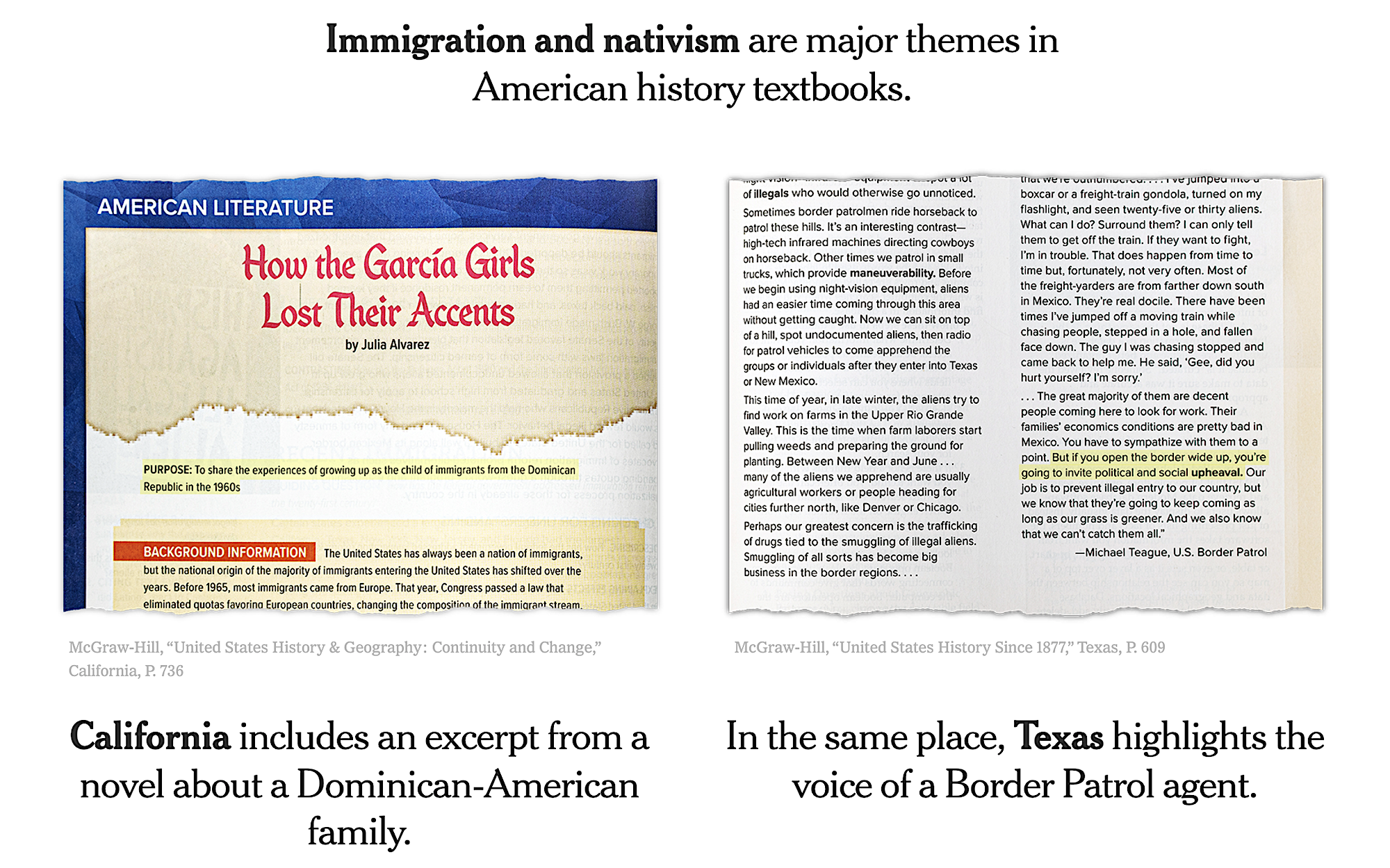

After this analysis of two different tellings of history, we looked at this astonishing New York Times interactive article on Texas versus California textbooks that recently exploded onto many social studies media feeds. The piece lists significant differences between the same textbook as it was published for two states, on topics from the Second Amendment to border controls.

Source. Click to enlarge.

Who tells history? we asked. Who decides what history goes into textbooks? Historians, yes, but also politicians and community members and state/local board members.

Later, I wondered why this first half of class felt powerful. One answer is that these middle schoolers were thinking critically: first teasing out the differences in historical narratives for themselves, then seeing a direct connection to a current issue that many adults care about. The immediate application to the New York Times article made their growing skills seem authentic and relevant in the real world.

The second part of class was a little more conventional, with 15 minutes of Ken Burns’ Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, on which the students took notes, and 15 minutes of looking through the 1848 Declaration of Sentiments, part of a lesson plan by the Stanford History Education Group.

Clips from Burns’ program.

In pairs, the eighth graders wrote a word or phrase in the margin describing each of the grievances (with my help on vocabulary such as franchise and Jehovah) and starred the three “offenses” against women’s rights they thought were most appalling.

This second half of class felt like a fitting match to the first half for two reasons:

First, the Burns video set up the document perfectly, ending just at the moment when Frederick Douglass and Elizabeth Cady Stanton join forces to convince the Seneca Falls Convention to pass a resolution that women should gain suffrage.

Second, just as we had compared two similar narratives in the first half of class, in this second part we also were able to view the same topic, the Seneca Falls Convention, through multiple lenses.

My conclusion: The energy in this block-period lesson arose from several closely linked looks at the same content, plus critical thinking and partner work. In addition, strong narratives humanized history in sometimes unexpected ways.

Lesson 2 – Almost No Sources, Just Questions

For the next lesson, during one of our short 43-minute periods, I originally had planned another document-heavy day: analyzing Susan B. Anthony’s 1873 speech, “Is It a Crime for Women to Vote?”, with an excellent lesson plan from Facing History and Ourselves.

The richness and realism of the document, I hoped, would complement the idealism of the Declaration of Sentiments written twenty-five years earlier.

And it would have. But my students led me to other plans.

We started, as I had intended, with a short video and photos from the 2020 Women’s March. These contemporary sources doubled as our daily current event, and I asked students to write down which rights they thought these mostly Democratic women were fighting for.

Source. Click to enlarge.

We talked about how hard it is for one march to encompass all the issues that people care about, from climate action to inclusion, and also that every woman at the march probably didn’t feel equally about every issue raised.

Originally I had intended the women’s march images as a springboard to a philosophical question I wanted to discuss before tackling Anthony’s 1873 civil disobedience, taken from the Facing History lesson: Is it always wrong to break the law?

But at this point in class, I realized that I wanted a little more buy-in, a little more personal connection. So I asked: What would a men’s march be about? Do we have men’s marches very often? Why or why not? Students brought up issues men might care about as a group, such as a higher suicide rate and toxic masculinity.

With their responses, students also probed some of the deeper issues underlying our reformers unit, such as the fact that people who do not have privilege often need to protest more than those who do have it.

After this impromptu question about a men’s march, I finally felt we had the energy and the setup for the original question about violating a law. In that moment, I also decided to postpone the Susan B. Anthony primary source assignment. Her conflict could wait until another day, but these underlying conundrums would thematically stay with us all year.

During the last part of class, students talked in in pairs about whether it is always wrong to break the law, wrote a sentence or two about it, and then used a Facing History discussion strategy to show how they felt about it.

In response, these eighth graders mentioned problems when everyone tries to work together on a broad cause, such as specific subgroups’ problems being ignored, as well as issues with specific groups working together rather than being part of the whole, such as splintering off and having too many competing interests. At the end, they took a few minutes to write about what they had taken from the discussion.

Why the Magic?

So what did I learn? Why did these two lessons, together, feel so much like what I want to accomplish each day in the classroom? Here are a few thoughts:

1. Just about every student participated meaningfully, actively and repeatedly, either in full-class discussion or in pairs or both. They found an entry point into reform and activism that they could refer back to in future current events and historical readings.

2. We moved from source to source in the first class, practicing different kinds of analysis depending on what it was – text, narrative, newspaper article, video, 19th century primary source. The connections felt fluid and rich.

3. We moved from question to question in the second class, playing with ideas, introducing or reinforcing concepts that are still pretty new to most of my middle schoolers. They could feel their minds opening.

Ultimately, these eighth graders acted as informed citizens, as they connected to themselves and the world, and I loved watching them grapple with texts and questions.

Will the magic happen again? Ideally, yes – but I can already tell you that we didn’t sustain it the third day. Class was interesting enough but not transcendent, possibly filled with too many sources in too little time. However, with these criteria for critical thinking success in hand, I’m hoping that these kinds of days might be conjured up a little more often.

Thanks for crafting this reflective analysis of what worked, for us fellow teachers. I would’ve loved to see these 3 days in action.

Something’s missing in your critical reflecting, though. You conclude that it was the content– well-chosen contrasting readings and your guiding questions– that sparked the thinking, discussing magic. I’m going assume there’s something just as important you barely hint at: the nature of your interactions with students. You led these lessons in a way that respected student voices and thinking, and gave your 8th graders the focusing structure that made everyone feel safe and able to participate. This is something you established over time. What a great feeling, right?!

Stephanie, this comment is so kind. Thank you for the uplift at the end of an online teaching day!