Why Media Literacy Matters in Science Class

“Houston, we have a problem,” reported the Apollo 13 astronauts (more precisely they relayed the distressing phrase “Houston: we’ve had a problem here”) when a major technical malfunction was discovered. Thus began the painstaking job of fixing the problem and bringing the astronauts home safely in 1970.

“Houston, we have a problem,” reported the Apollo 13 astronauts (more precisely they relayed the distressing phrase “Houston: we’ve had a problem here”) when a major technical malfunction was discovered. Thus began the painstaking job of fixing the problem and bringing the astronauts home safely in 1970.

Educators, we have another problem and this one won’t be fixed nearly so quickly. It’s “science illiteracy” – the failure of young people to think, or act, critically on “scientific” information they receive from social media and YouTube.

The problem was highlighted recently in “The War on Science” broadcast by CBSN – the online news network of CBS News. It appears that students, who are heavy viewers of YouTube, are coming into class woefully misinformed.

Among other things, it is clear that some students believe in often-ridiculous conspiracy theories and misinformation (the Earth is flat; climate change is a hoax) that are propagated in some social media. And they bring these misconceptions into the classroom.

(Source)

“There are actors online who are willfully spreading misinformation,” said CBS reporter Adam Yamaguchi, “knowing that it’s misinformation, knowing that there’s this huge audience for it.” This huge audience is found at YouTube, where more and more young people are getting their information. Everyday, millions of young people are logging on and watching YouTube videos.

After surveying science educators in 2016, researchers from Pennsylvania State University and the National Center for Science Education concluded that “The lack of teaching and the mixed messages about climate change leave schoolchildren more susceptible to disinformation about climate change spread by political or corporate interests once they enter adulthood.” (Source)

“Science education is perhaps one of the best tools we have to help students resist that kind of misinformation,” said Ann Reid, executive director of the nonprofit science advocacy group National Center for Science Education (NCSE). Her organization has recently compiled lesson plans and other resources to help teachers combat the misinformation students are getting about climate change, for example.

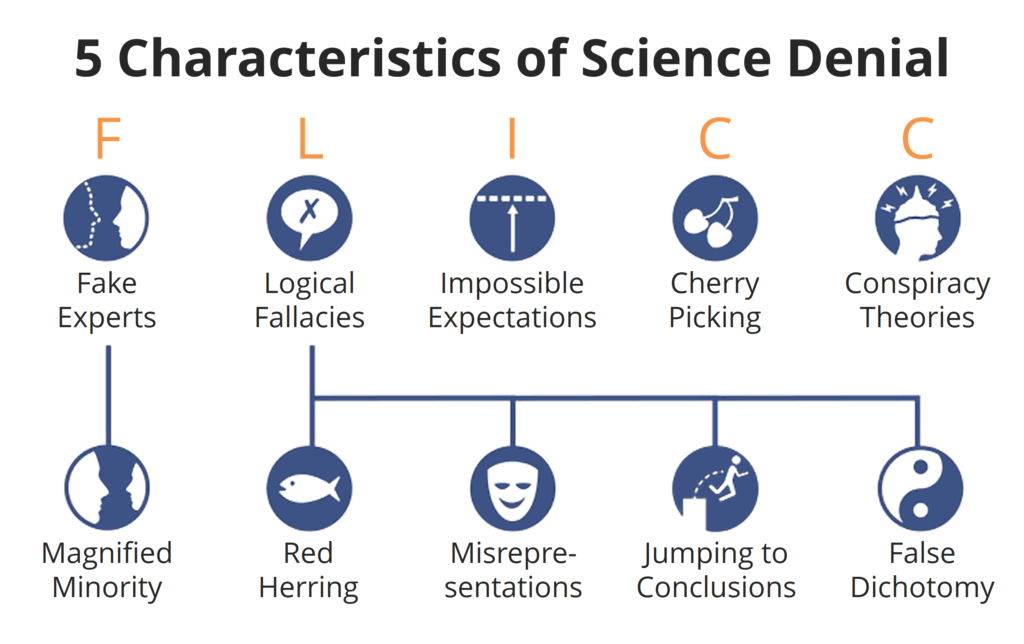

One of the strategies promoted by NCSE is teaching the Five Characteristics of Science Denial. Using the graphic (below – click to enlarge) students are taught to identify one or more characteristics being used by the creators of the messages. Melissa Lau, a middle school science teacher from Oklahoma featured in the CBSN news story, noted that it’s not just about science, but rather teaching students how to navigate a world where “truth” is changing. She adds, “it’s a survival skill in this day and age.” (Source)

Are students coming to class putting more faith in misleading YouTube videos than instruction from qualified teachers? That’s a question that needs to be considered.

The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) in collaboration with the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) wrote in 2004 that students are expected to:

“Gather, read, and synthesize information from multiple appropriate sources and assess the credibility, accuracy, and possible bias of each publication and methods used, and describe how they are supported or not supported by evidence.” (Source)

More recent evidence indicates today’s students have trouble assessing the credibility of information, so it’s clear more time needs to be spent helping students analyze sources.

To assist educators, three researchers have created a free, research-based, one-week curriculum unit for use in grades 6–12. Recently published in NSTA’s Science Teacher magazine, it consists of four units:

1) Misleading Advertisements

2) Asking The Right Questions

3) Understanding Science and

4) Reliable Information.

“By teaching how to judge the quality of scientific claims encountered in media,” the researchers wrote, “teachers provide students with skills and dispositions that will serve them throughout their lives.” (Source)

The amount of misinformation is vast

Teachers face a host of challenges when it comes to instructing young people. The new challenge is the vast amount of information – or more precisely – the misinformation they are receiving from social media. Teaching healthy skepticism ought to be one of the goals.

Media literacy, which encourages the critical inquiry of media messages, becomes even more important. Unfortunately, it has been my experience that most educators have not had one minute of training in media literacy, and have received little if any support to pursue this aspect of professional development. As a result, they are not prepared to help their students see through the techniques used by media makers who want our attention and our clicks. And from their perspective, the more credulous we are, the better.

Recommended Resources:

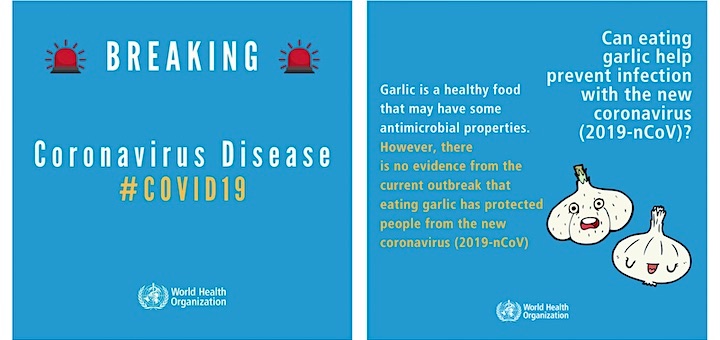

►Fake Facts Are Flying About Coronavirus. Now There’s A Plan To Debunk Them (NPR)

►Resisting Science Misinformation Teacher Guide and Four-Lesson Unit (NOVA)

►Misinformation is Everywhere: These Scientists Will Teach You How to Fight BS

(For older students or teacher background)

►Communicating Science Effectively: A Research Agenda (NAP)

►Understanding and Countering Misinformation About Climate Change (2019 – PDF)

Here’s How Scientific Misinformation, Such As Climate Doubt, Gets Spread on Social Media (WaPo)

►26 Million Americans Are Scientifically Illiterate (MIT Technology Review)

►Media Literacy Questions Every Teacher & Student Needs To Consider (medialit.org)

►Guiding Students to Science Literacy (Edutopia)

►Combating Students Misconceptions (NSTA Science Scope, 2005)

►Infographic: The Best And Worst Science News Sites (American Council on Science & Health)

►Coronavirus: Hydroxychloroquine Probably Isn’t the Answer (ACSH, March 2020)

►Science proves why people on social media ignore facts (Big Smoke – Australia)

►Climate misinformation may be thriving on YouTube (Science News for Students)

►Scientists enlist computers to hunt down fake news (Science News for Students)

►NSTA Press authors Laura Tucker and Lois Sherwood provide an engaging lesson in “Fact or Phony? Scientifically Evaluating Data” from Understanding Climate Change, Grades 7–12, a 36 page teacher guide. Students explore a purely fictional web page cleverly designed as factual and are challenged to consider whether the “Pacific Northwest tree octopus” is, in fact, in danger of extinction due to the effects of climate change. By reviewing data and evaluating their validity as well as using reputable sources of data, students practice key methods to sort out fact from phony.

Free Science Literacy Course Announced

Thinking critically is not a superpower. But the University of Alberta is offering a boost to critical thinking about science with a free online course — how to tell the difference between sound scientific studies and pseudoscience.