Fresh Learning Designs for Uncertain Times

Read Sarah Cooper’s review of Lindsay Portnoy’s book Designed to Learn (ASCD, 2019) here at MiddleWeb.

During regular times the goal of most educators is to provide students with choice in their learning and a voice in sharing their learning with peers and the world at large.

In enacting choice and voice, the continuous goal is cultivating a community of engaged and passionate learners. But what does it mean to create choice, voice, and community and what happens when learning goes online?

One answer is to be sure we infuse learning with purpose. Purpose is the fuel that propels passionate learning in classrooms, family rooms, and boardrooms. Regardless of the venue, learning that is relevant and meaningful is the learning that can be applied today and in the future.

These intentional and flexible approaches to learning at home and at school are readily available and immediately useful through the lens of design thinking.

Design thinking is at its root scientific thinking with the added bonus of empathy and attention to perspective. It is also a process used widely in industries from music and engineering, to finance and marketing, and contains essential 21st century skills from critical thinking and communicating to creation and collaboration.

But what does design thinking actually look like in a classroom or living room?

A traditional fourth-grade curriculum requires students to learn about the history of their community while an eighth-grade curriculum asks students to understand exploration and colonization. Both require students to use primary and secondary sources to acquire this information, but in traditional modes of learning the goal is to later recall discrete facts.

By contrast, a fourth-grade history unit becomes a product of design thinking when students use teacher-curated sources about changes to population over time in an effort both to explain historical changes to local industry but also to define the needs of the current community. Similarly, eighth-grade students tackle a unit on exploration and colonization with design sprints that help determine the impact of population growth on carbon emissions in their community today.

Both instances provide developmentally appropriate, interdisciplinary, and substantive learning experiences. And if scaffolded intentionally over time starting right now, students will slowly get the hang of owning their learning and will be poised to meet whatever uncertainty faces them in their future.

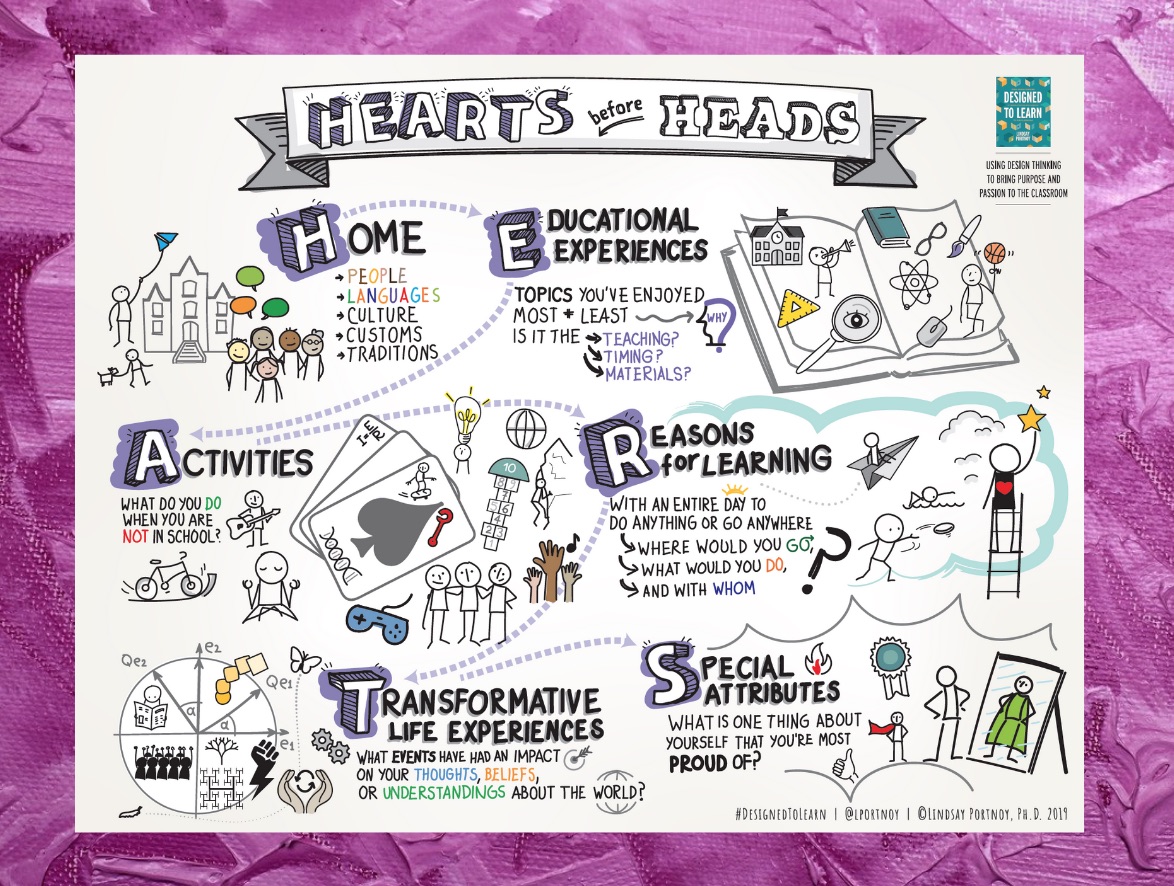

As an iterative process for learning, design thinking is rich with resources that allow students to take ownership of their knowledge acquisition by connecting directly to the content in meaningful ways. Learning impacts hearts before heads – more specifically, by connecting to your students’ homes, educational experiences, the activities they engage in, their reasons for learning, transformative life experiences, and special attributes that make them unique!

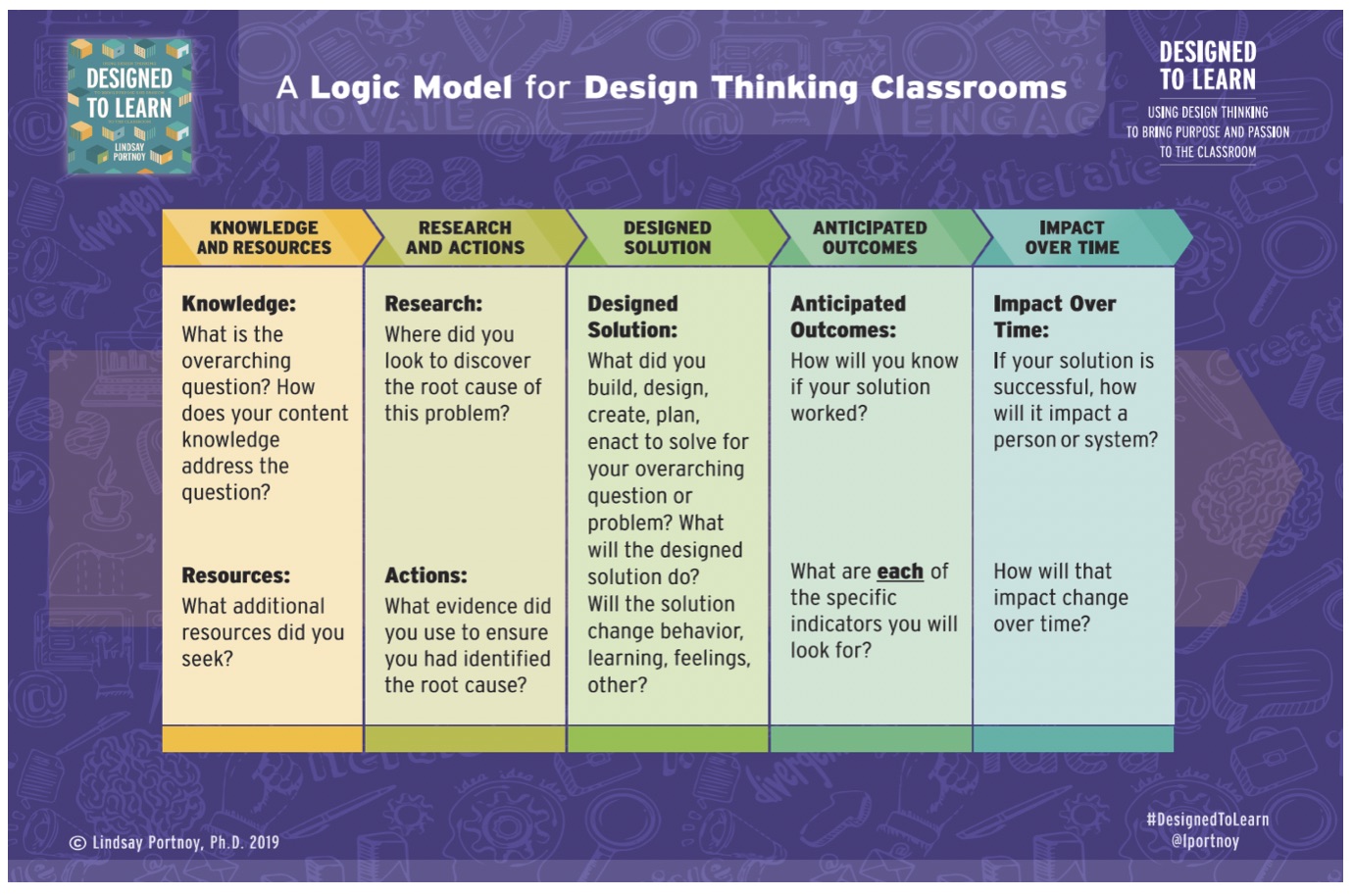

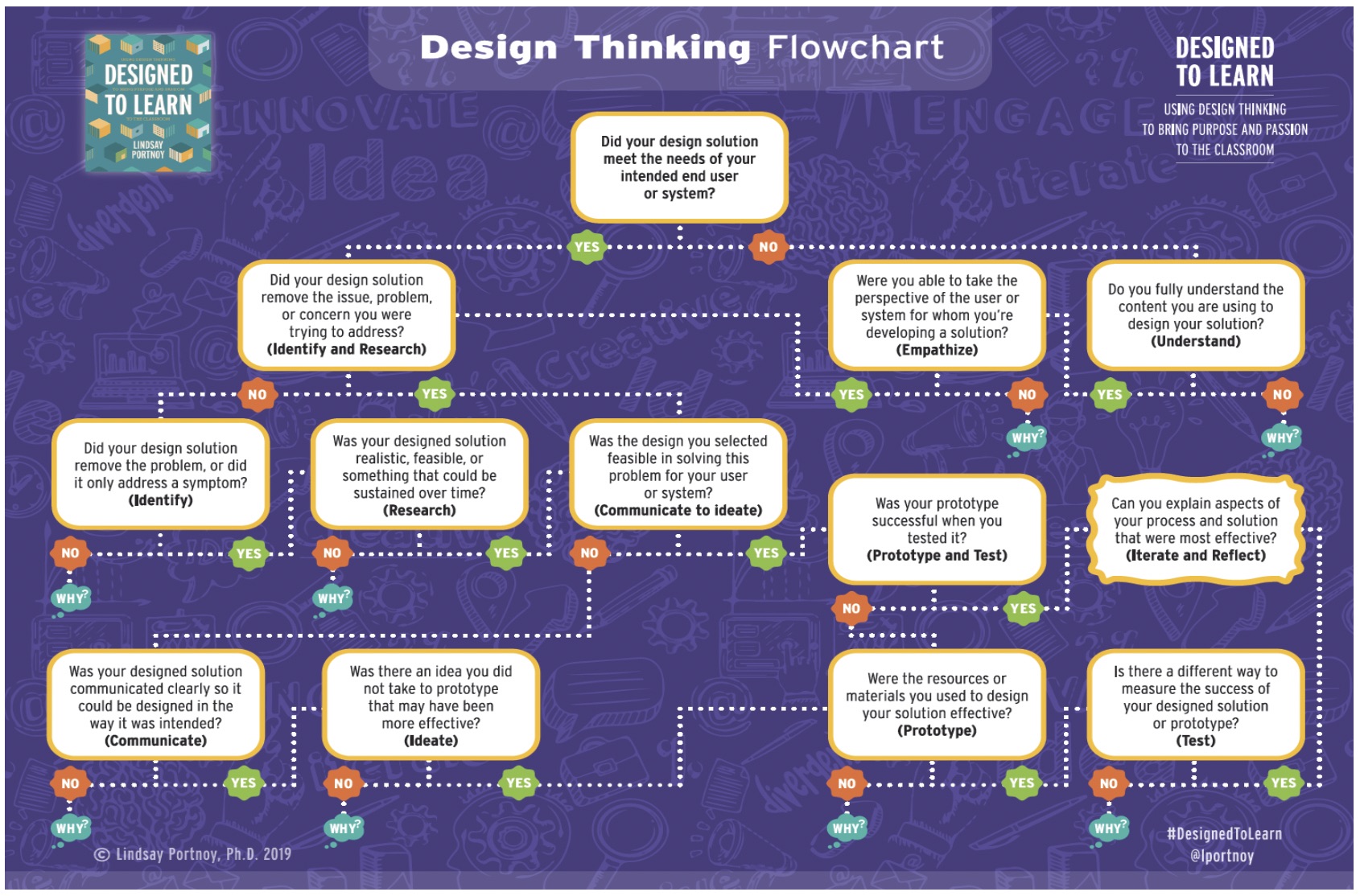

The elements of design thinking include:

• understand for empathy,

• identify and research,

• communicate to deepen thinking,

• prototype and test, and

• repeat and reflect.

These five elements are already alive in many lessons throughout the school year and a few small shifts can make them readily apparent each day. What’s more, in using these intentional and flexible pathways for learning, students receive clear and consistent feedback that is then received as less of a ‘gotcha’ and more of an opportunity for growth.

Whether learning will happen in the classroom or virtually, the first step in design thinking is to look at the goal for the learning. To begin, fill in the parentheses of the following simple sentence:

Understanding (content) will help my students (application to life).

This simple sentence is foundational. Discrete skills in literacy and numeracy are necessary for comprehension and critical thinking. However, if the sole purpose of learning about colonization is to regurgitate the 13 colonies we’re no longer training students but instead cultivating sentient robots.

With the simple sentence complete, the purpose for learning is relevant and visible and you’re ready to spark your first design sprint. A history teacher’s sentence may read: understanding (exploration) will help my students (see how geography impacts economy). Or a math teacher’s sentence may read: understanding (probabilities) will help my students (predict likely outcomes from pandemics to precipitation).

You’ve set the stage by curating content, and perhaps you’ve given a mini-lesson or shared a reading, video, or interview on a specific topic. It’s time to stand back and let your learners take the wheel to create solutions or innovations that will impact the world around them using the content in a meaningful way.

The following five essential elements of design thinking will transform traditional instruction into inspired design sprints in any learning space. Student responses to questions as they move through the design sprint are formative assessments that show content mastery for certain. But they show far more than just content. Student responses to these inquiries demonstrate critical thinking, perspective taking, reflection, and even changes to students’ beliefs about knowledge and knowing (epistemology).

1. Understand for Empathy

Understanding: How can this content make a meaningful change in the world? What systems or experiences that are currently in place could I change with my knowledge and understanding?

Empathy: What person or system are you designing an innovation for? Interview a person or representative from the system for which you are designing a solution, or write a letter from the perspective of the person or system for whom you’re designing a solution.

2. Identify and Research

Identify: What are three reasons why this change is needed?

Research: Which one of these reasons is the root cause, or the cause that if removed would make the problem go away completely? How will I know this for certain?

3. Communicate to Deepen Thinking

Communicate: What do your peers, community members, caregivers, or experts think about the root cause you’ve identified? If the sky’s the limit, what would you create to innovate in this space?

Ideate: Which idea would be most successful? Why? How would you really know if your solution was successful?

4. Prototype and Test

Prototype: What could you design to innovate? Is it a concrete solution like changing the traffic pattern in a town or is it an iteration to an intangible solution such as changing the start time of school to see if it reduces absences?

Test: Is your test audience for the prototype representative of those whose needs are being addressed?

5. Iterate (Repeat) and Reflect

Iterate (Repeat): How did your solution work? How do you know? Try it again and again. Does it need to be changed anywhere? Where would you go first?

Reflect: What about this design activity could you use in other aspects of your life? What would you do differently next time? When were you most excited, nervous, empowered?

Thinking Ahead

Some considerations for teachers to think of ahead of time include: what is the purpose of the learning experience? What information will you provide explicitly and what information will students have to seek out? How will you support learners in finding credible information when they are invited to seek out extraneous knowledge?

In what ways can students collaborate with one another, their peers, caregivers, and experts to extend and push their thinking? How will you share feedback with students, and how will they share feedback with one another? How will you invite students to iterate on their work? And perhaps most importantly, how will you celebrate the results of these design sprints with the world at large to inspire a whole new way of teaching and learning?

The elements of design thinking can be applied in any space, in any order, and across any subject area. In fact, once students are empowered through design thinking experiences the role of teacher moves off the stage and into the wings where we observe from a distance and watch as authentic learning unfolds.

If this watching is done well, the teacher stealthily swoops in to check on learners, provides just-in-time support, and stands back while learners productively struggle forward with just the right support to learn how to learn.

A word for the weary

Design thinking should not be yet another initiative to add to the swinging pendulum of initiatives. Instead design thinking should be implemented as a novel approach to teaching and learning where a series of simple scaffolds gradually releases students to become autonomous in their learning. In this way we will finally bring about the depth of engagement and interest we know is possible when learning is loved.

I believe this novel learning experience is an opportunity to innovate on our antiquated system of education. In doing so we might birth an entirely new way of learning driven by purpose and passion.

Appreciate the recommended starting point in design–empathy! This is always important, but so important as we communicate from tech platforms. I’m motivated to read your book!

Watch for a MiddleWeb review of Lindsay Portnoy’s book later this month. History teacher Sarah Cooper writes that “By the time I finished Designed to Learn, I felt refreshed and finally ready to overhaul the Constitution unit that has needed more student voice for a while now.”