Understanding Autism Through Its History

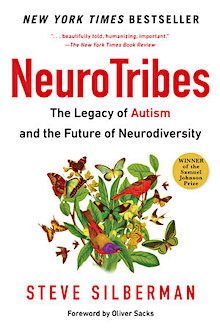

NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity

By Steve Silberman

(Penguin Random House, 2016 – Learn more)

My younger brother has autism, and for years I have tried to educate myself through different websites, articles, and books. I can confidently say if you are looking for a book that acts as an all-encompassing start to your journey in autism education, NeuroTribes is the book for you!

I would like to be clear that this book is not strictly a parental guidebook or a book for educators. Rather, this book is a resource that provides a rich history of autism including the founding psychiatrists, case studies, social and political influences, its naming, and much more.

NeuroTribes: A General Overview

The author describes a wide range of influences on autism discussions, from Hitler and Nazi Germany, the movie Rain Man, the development of HAM radios, Fandoms, the Internet, and the rise of the autistic community. The book’s title includes The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity, although more of the past is covered than the future.

The Organization

The book is divided into 12 chapters, each chapter further divided into subsections numbered with roman numerals. The subsections act as points of continuation from the topic which precedes them or act as points of separation that allow a deep dive into a specific point previously mentioned.

These subsections can further be broken off into what I began to think of as relevant tangents, indicated by an un-indented paragraph, where another topic or person is described. While this set up sounds like it can become confusing, the topics actually merge back together smoothly through the chapter.

For example, in Chapter 3’s “What Sister Viktorine Knew,” Section III provides descriptions of Asperger and his work with a child named Gottfried, but then jumps into an account of another psychiatrist named Grunia Sukhareva and her work with her patients. The section shifts back to Asperger, and Section IV begins by commenting on both of their work in relation to one another.

The book itself is a hefty 459 pages. This is a relatively big book that is best read a chapter, or a few sections, at a time.

An Engaging If Misleading Start

Chapter 1 titled “The Wizard of Clapham Common” and Chapter 2 titled “The Boy Who Loves Green Straws” gave me the impression that the book was going to look at individuals and relate their stories to specific topics of discussion within the autistic community.

For example, “The Wizard of Clapham Common” told the stories of Henry Cavendish and Paul Dirac, both brilliant 18th/19th century scientists who are speculated to have had a type of autism called Asperger’s syndrome, and the chapter brings up the idea of historical representations of autism. “The Boy Who Loves Green Straws” provides an account of an autistic boy named Leo (who loves green straws) and his mother Shannon as she began looking to cure her son with different diets and biomedical treatments.

With these two chapters, I was expecting the remaining ten to follow the same sort of structure: Introduce a person, tell about their life and how autism plays a role in it, and relate it to an overarching topic. The remainder of the book though seemed to be written as more of an easy-to-read historical account.

This is by no means a bad thing, just an unexpected format after the first two chapters. Chapter 6 “Princes of the Air” and Chapter 9 “The Rain Man Effect” both gave reminiscent vibes of the first two chapters, and were probably my favorite chapters in the book.

I will also note here that Chapter 2 “The Boy Who Loves Green Straws” feels almost out of place in the narrative, as it covers topics like the influence of a blog and biomedical treatments after the chapter that covers 18th/19th century scientists and before the chapter that jumps into the early 20th century.

Though out of place, putting it in its appropriate place in the narrative would have disrupted the flow, organization, and tone of the later chapters, so I can see why it was placed where it was placed, and it is too important of a chapter to not include.

Interweaving Stories

As the book focused more on a historical account of autism, I began to see the book as a quilted blanket, with each subsection of a chapter interweaving with one another to create a holistic picture. At the end of a subsection, there would often be a phrase that suggested what was to come. For example, Chapter 11 Section IV ends with the question “Could an aggregation of loners become a movement?” (p. 456)

This interweaving set-up sometimes got a little confusing as the jump from one psychiatrist’s story to another sometimes felt like an information overload, but overall it all seemed to still flow nicely. There were times where I did not know where the story was going, but then it would tie back into the topic of autism.

For example, at one point Chapter 6 “Princes of the Air” began to feel like an account on the history of fandoms rather than autism, and I was unsure how it fit into the narrative, but then the author wrote that “For people on the autism spectrum before it had a name, [Gary Westfahl, a science fiction historian] explains, the alternate universe of science fiction may have felt less alien than the baffling sea of mundania in which they found themselves marooned.” (p. 239)

The chapter goes on to explain how fandoms like science fiction acted as a community where many, including people with autism, could come together under a common interest. Those on the autism spectrum felt like they could find a community where they belonged while living in a world where they felt all too often excluded.

My Final Thoughts

Silberman provides a fair, unbiased account on the history of autism. This is the perfect book for anyone who is interested in the topic of autism, whether you are new to the subject, semi-familiar, or expert in the field.

I would be remiss if I did not end this as I try to end any conversation I have about autism, by paraphrasing a popular quote: I wouldn’t change my little brother for the world, but I will try to change the world for him. Thank you for your interest in autism, and happy reading!

Daniel Zarasua is an undergraduate student at Pepperdine University who hopes to teach math in the near future.

Hear Steve Silberman’s live conversation with 15-year-old Dara McAnulty, author of Diary of a Young Naturalist, at the Hay Festival May 22, 2020. It airs 12:30 pm in Great Britain, but will be available for 24 hours. Diagnosed with Asperger’s/autism at age five, the young Irishman says, “Nature became so much more than an escape; it became a life-support system.” https://www.crowdcast.io/e/hayfestival_event4/register