Reading Strategies in the Science Classroom

MiddleWeb is featuring excerpts from three new books edited by the editorial team of Larry Ferlazzo and Katie Hull Sypnieski, both teachers in Sacramento CA and co-authors of The ELL Teacher’s Toolbox. Last week’s excerpt on teaching current events highlighted The Social Studies Teacher’s Toolbox. Also see: The Math Teacher’s Toolbox.

By Tara C. Dale and Mandi S. White

Tara

Why is reading comprehension an important part of science?

Being able to read and comprehend informational text is a skill all students will need in life. Science classrooms are places where teachers naturally incorporate informational text into daily lessons.

As students strengthen their reading skills they also have the opportunity to build background knowledge around new content. Good reading comprehension can also help our science students to extend knowledge after labs and other interactive activities.

Using a 4×4 reading strategy

Mandi

The 4×4 reading strategy requires students to read a text four times for four different purposes. When students interact with texts multiple times, they may have an increased understanding, especially of more complex texts.

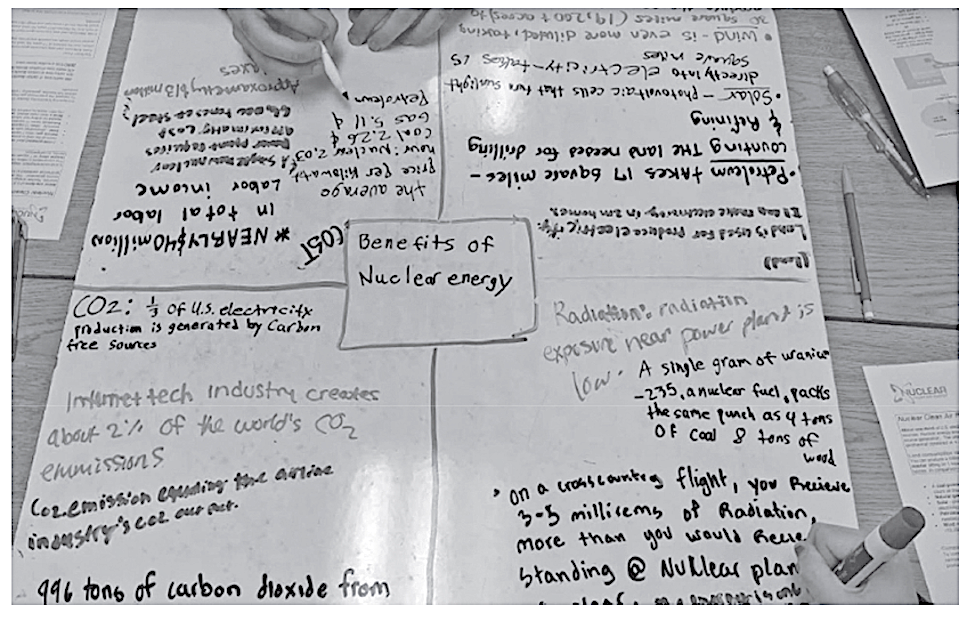

We start planning a 4×4 activity by choosing four topics that could be discussed within an article. For example, after teaching students the drawbacks of nuclear power plants, we have them read an article titled “The Benefits of Nuclear Power.” Four topics from the article that can be discussed are:

1. Cost

2. Land

3. Carbon dioxide (CO2)

4. Radiation

After we find the article and identify the four topics, we follow these steps during the lesson:

1. Students are divided into groups of four.

2. Each group is given a large piece of paper or whiteboard and each group member receives a different colored writing utensil so we know the identity of the writer.

3. On the classroom board, we model what we want students to draw on their paper. We begin by drawing a square in the middle, which is where the theme of the article is written. In this case, “The Benefits of Nuclear Power” is written in the middle box. Students are instructed to duplicate this middle square on their paper.

4. Then, on the board, we draw four equal sections. Students do the same on their large papers.

5. Once everyone has the basic format written on their paper, we add the four section titles on the board to model how students should label their four sections. In our example, the four sections are titled, “cost,” “land,” “CO2,” and “radiation.” Note that to save time, these papers can be premade.

6. Each group member receives a copy of the article. They are instructed to read the text searching for any detail that pertains to the section’s topic they have in front of them. They receive two minutes to read the text and write down at least one detail.

7. After two minutes, students are instructed to stand up and rotate clockwise so they are sitting in front of a new section. In other words, four students are sitting around one piece of paper and they are rotating around that piece of paper.

8. Students receive 30 seconds to read what the previous student wrote because they cannot duplicate it.

9. Students then receive 2.5 minutes (30 seconds more than the previous time) to read the article a second time, and search for an additional detail that pertains to this new topic.

10.This continues until every student has read the article four times – each time in search of a detail that hasn’t yet been written down. And every time students switch seats, they receive an additional 30 seconds because they’ll need this extra time to find the more obscure details their peers didn’t find.

Here is a student example of a 4×4 board:

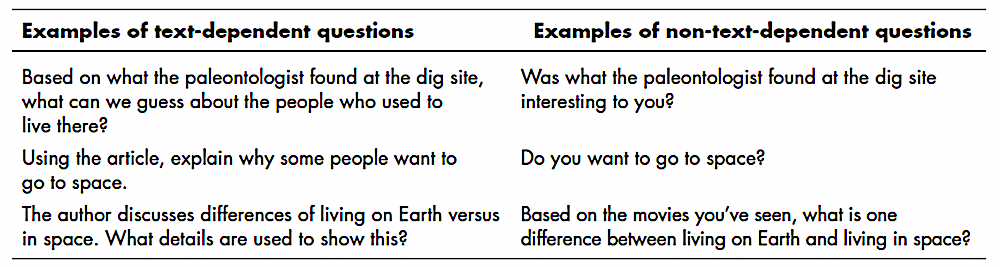

Using text-evidence questions

Text-dependent questions require students to return to the text to find not just the answer, but also evidence to support their response. Text-dependent questions should not ask students about simple facts, but, instead, require them to make inferences, predictions, or conclusions.

Text-dependent questions are important because they reinforce the idea of rereading something to ensure comprehension.

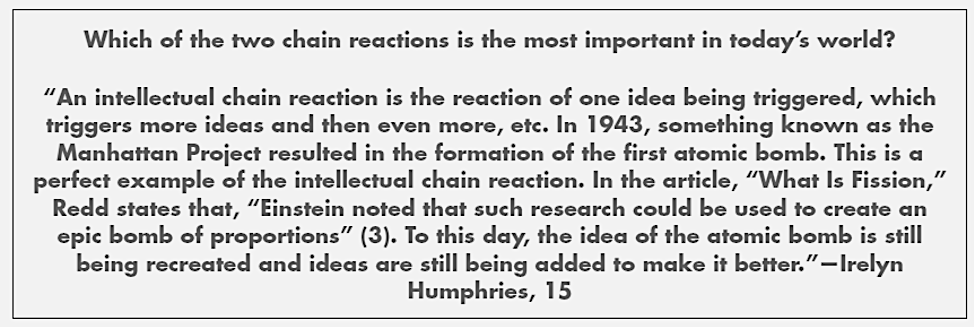

As an example, after reading an article about the history of how an intellectual chain reaction discovered fission and how fission itself is another type of chain reaction, we asked our students this text-dependent question: “Which of the two chain reactions in the article is the most important in today’s world?”

After reading the text, 15-year old Irelyn Humphries, one of our students, used the information to decide that intellectual chain reactions were more important than fission. Her answer included a quote regarding Albert Einstein’s research that she chose as evidence to support her opinion.

Using graphic organizers

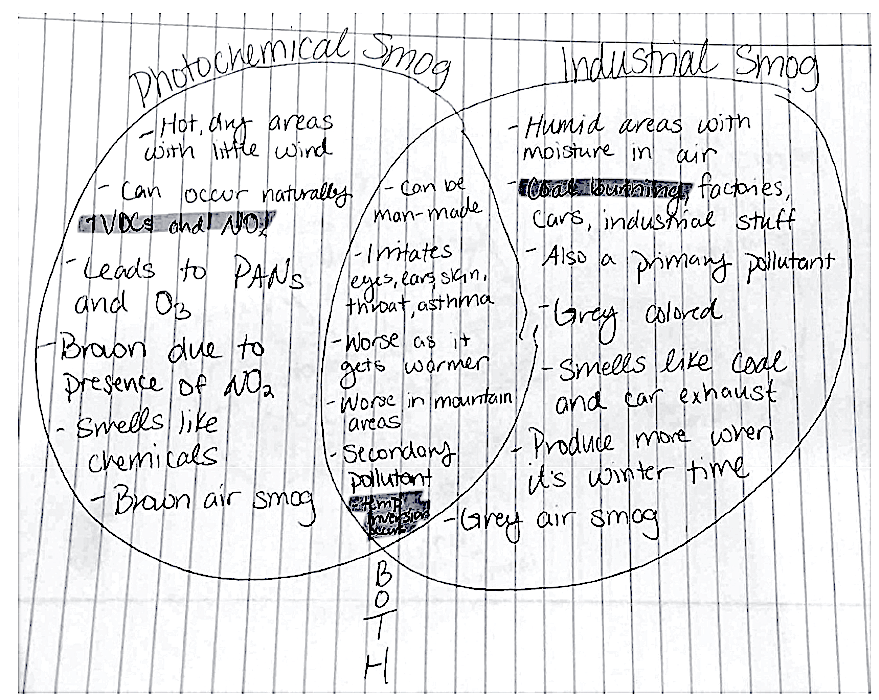

Graphic organizers are tools that help students visually organize information. Research has found that they are effective in helping students identify and recall main ideas from their reading and may increase comprehension.

An example of a graphic organizer is a Venn Diagram, which is used to compare and contrast two concepts. After students read an article or textbook excerpt, they compare and contrast two things, such as photochemical and industrial smog.

The students draw two overlapping circles, labeling each with one of the two concepts. Where the two circles overlap, they write what the two concepts have in common. The unique characteristics of each concept is written in the portion of the circles that do not overlap. Here is a student example:

These three reading strategies require students to interact with the text multiple times, which can result in an increased understanding, especially of more complex texts. Comprehending complex informational text is a challenge for many students. The use of reading strategies that expose students to text multiple times can assist with comprehension.

Mandi S. White is currently an academic and behavior specialist at Kyrene del Pueblo Middle School in Chandler, Arizona. She has worked as a middle school special education resource teacher and has taught English, Social Studies, and Math. She holds Master’s Degrees in Special Education and Educational Leadership, and a graduate certificate in Positive Behavior Support.

They are the authors of The Science Teacher’s Toolbox: Hundreds of Practical Ideas To Support Your Students. (Jossey Bass, 2020)